[Please click on blue links for further information]

“Donald Trump – a ludicrous figure, but at least he’s lived it up a bit in the real world and at least he’s worked out how to cover 90 per cent of his skull with 30 per cent of his hair … It always makes me suspicious when, you know, you have these apolitical businessmen saying well I just want to, you know, to put the country back on its feet and restore incentives and so forth. There’s something frankly, I think, sinister about it unless the guy is prepared to say a great deal about what his political opinions are. For example, has he ever voted before and for whom. I’d like to know because its much too easy a story … for the country to be run by USA Inc. with a real “can do” guy, there’s a whiff of fascism to that I think.” Christopher Hitchens

“And, indeed, as he listened to the cries of joy rising from the town, Rieux remembered that such joy is always imperiled. He knew what those jubilant crowds did not know but could have learned from books: that the plague bacillus never dies or disappears for good; that it can lie dormant for years and years in furniture and linen-chests; that it bides its time in bedrooms, cellars, trunks, and bookshelves; and that perhaps the day would come when, for the bane and the enlightening of men, it would rouse up its rats again and send them forth to die in a happy city.” Albert Camus, The Plague (last paragraph)

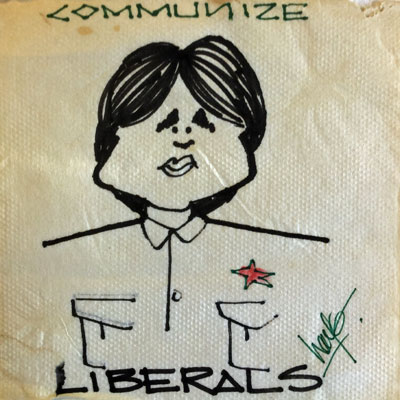

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, artist unknown

Donald Trump—buffoon, clown, narcissist, brilliant businessman—whatever you think of him, he is a gift to the comedy industry. He’s also a gift to novelists and to the media he so much dislikes. He was one of the first apparently to take advantage of this fact with a novel of his own called Trump Tower touted in typical Trumpian fashion as “the sexiest novel of the decade.” It’s rumored that Trump himself wrote the book or assisted in the writing. The ghostwriter, Jeffrey Robinson, refuses to comment. One wonders how The Tweeter in Chief could have produced anything beyond 140 characters. But, if he did, Trump Tower seems like a credible candidate.

Billionaire Ray Dalio, who extolls the opportunities to make money under Trump’s policies, suggests reading the Ayn Rand novels Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead to get a taste of what’s coming. As someone whose business card has a quote from Flannery O’Connor, I’m sorry but I cannot recommend Ayn Rand. I’ve read two biographies, and they are not impressive. Rand is House Speaker Paul Ryan’s favorite author. He passed out her books to his entire staff. God help us. Flannery O’Connor, a real writer, said this about Ayn Rand:

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, artist unknown

In the 1940s, Flannery O’Connor wrote a short story, The Barber, about a politician named Mr. Hawkson, “Hawk” for short, who cannily resembles The Donald.

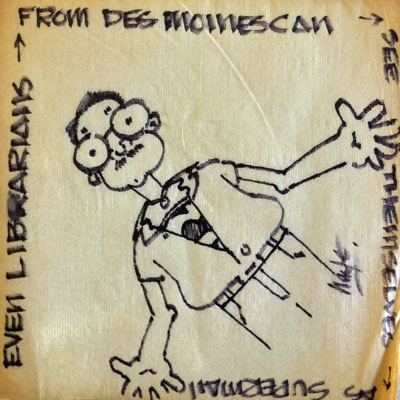

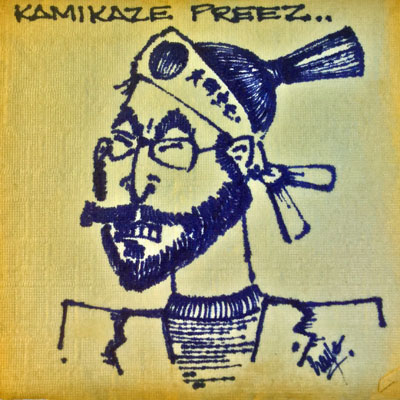

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Jack Haye artist

“You ever heard Hawkson talk?”

“I’ve had that pleasure,” Rayber said.

“You heard his last one?”

“No, I understand his remarks don’t alter from speech to speech,” Rayber said curtly.

“Yeah?” the barber said. “Well, this last speech was a killeroo! Ol’ Hawk let them Mother Hubbards have it.”

“A good many people,” Rayber said, “consider Hawkson a demagogue …”

“Demagogue!” The barber slapped his knee and whooped. “That’s what Hawk said!” he howled. “Ain’t that a shot! ‘Folks,’ he says, ‘them Mother Hubbards says I’m a demagogue.’ Then he rears back and says sort of soft-like, ‘Am I a demagogue, you people?’ And they yells, ‘Naw, Hawk, you ain’t no demagogue!’ And he comes forward shouting, ‘Oh yeah I am, I’m the best damn demagogue in this state!’ And you should hear them people roar! Whew!”

The “Mother Hubbard” liberals of today would have about as much chance of convincing their barbers, in some cases friends and family, that Trump is a demagogue as the poor, ill-equipped professor Rayber had in Flannery O’Connor’s story.

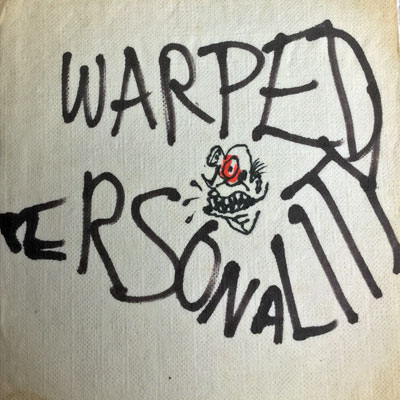

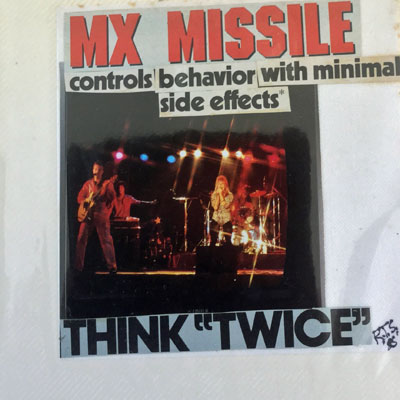

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, artist unknown

But, Trump is not a new phenomena. We’ve seen his kind before. The comparisons are legion. He has been compared, for example, to Dostoevsky’s protagonist in “Demons,” Pyotr Verkhovensky. Or, to Philip Roth’s fictional account of Charles Lindberg in The Plot Against America, or Buzz Windrip in the Sinclair Lewis novel It Can’t Happen Here.

“Donald Trump, like Lindbergh, arrives at his position as an established personality rather than as a politician. Of course, while Roth’s 1940-era Lindbergh is a classic, rugged, Midwestern man of few words, Trump’s vulgarity is part of his appeal. On the campaign trail, Lindbergh’s anti-Semitism is implied; Trump does nothing to tamp down his rhetoric about Muslims and immigrants. In some ways, Trump is more accurately a synthesis of Roth’s Charles Lindbergh and Buzz Windrip, the fascist U.S. president from Sinclair Lewis’s 1933 cautionary tale It Can’t Happen Here.” [Quote From The Guardian]

The fact that Donald Trump is old hat is of no particular importance. He has the character of many a fictional construct. Sadly he also resembles too many of the actual people we’ve heard about, read about, and seen. George Meredith in his tedious but somewhat interesting and humorous classic The Egoist does as good a job as any of describing what it is that honks Trump’s horn.

“Of the hundred and fourth chapter of the thirteenth volume of the Book of Egoism it is written: Possession without obligation to the object possessed approaches felicity.” George Meredith, The Egoist, Chapter 14

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, artist Max Effrom

What is different today is that such a man is about to become our President. What that means for the future of America is as yet unknown but the very fact of The Donald’s arrival says volumes about who we are and who we think we are. Trump lost the popular vote by nearly 3 million votes, over 2%, the worst of any other elected President except for Rutherford B. Hayes and John Quincy Adams.

And yet …

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, artist unknown

Stephen King, “author of horror, supernatural fiction, suspense, science fiction, and fantasy,” penned a “tweet” long before the election that is worthy of The Donald himself:

@StephenKing

Populist demagogues like He Who Must Not Be Named aren’t a new thing; see THE DEAD ZONE, published 37 years ago.

6:25 AM – 15 Mar 2016 1085 Retweets 2796 Likes

King was tweeting about a character in his novel The Dead Zone, Greg Stillson, the door-to-door bible salesman who runs for President. The novel was adapted into a movie of the same name and later into a TV series. Anne Sewell at the Inquisitr had this to say about Stephen King’s character Greg Stillson:

It is what happens at Stillson’s political rallies that has got people comparing him to Donald Trump. What happens in King’s version of a political saga is that Stillson takes to the stage wearing a “hi-impact construction worker’s helmet cocked at an arrogant, rakish angle on his head.”

While it’s not a red made-in-China cap reading “Make America Great Again,” Stillson’s explanation for his helmet is as weird as anything The Donald could come up with.

“You wanna know why I’m wearin’ this helmet, friends ‘n neighbors? I’ll tell you why. I’m wearin’ it because when you send me up to Washington, I’m gonna go through ’em like you-know-what through a canebrake! Gonna go through ’em just like this!”

Reportedly, Stillson then went running up and down the stage like a bull, yelling as he went.

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Jack Haye artist

There is no shortage of attempts to compare flawed fictional characters to our Tweeter in Chief, no hesitation to recommend novels based on these characters to a public unlikely to read anything over 140 characters. Hope springs eternal. The Atlantic did an article on Trump’s Dystopias a year ago mentioning such classics Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and less well known pieces such as a recent short story, Arctic Lizard by Etgar Keret available HERE online. At the progressive blog site Daily Kos, Donald Trump is compared to Big Brother in Geroge Orwell’s 1984. At BUST, “the groundbreaking original women’s lifestyle magazine and website” there is a post on “11 Dystopian Novels To Prepare You For Donald Trump’s Presidency.” Why 11? The article doesn’t say. At Bedford + Bowery you can take a quiz to see if you can tell the difference between 14 quotes from Donald Trump and 14 quotes from Carmac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian.

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, RTS artist

One could point to Ecclesiastes as the forerunner to all of these. If the Bible is too wordy a book for you, try humming the lyrics to Turn Turn Turn written by Pete Seeger and recorded by The Byrds.

To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven:

A time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, a time to reap that which is planted;

A time to kill, and a time to heal; a time to break down, and a time to build up;

A time to weep, and a time to laugh; a time to mourn, and a time to dance;

A time to cast away stones, and a time to gather stones together;

A time to embrace, and a time to refrain from embracing;

A time to get, and a time to lose; a time to keep, and a time to cast away;

A time to rend, and a time to sew; a time to keep silence, and a time to speak;

A time to love, and a time to hate; a time of war, and a time of peace.

Literature is used and misused for all sorts of reasons. This attests to the fact that a good book is still relevant even in the world of texts and tweets. I recently came across a fascinating article on William Blake and Donald Trump that caught my eye. I’ve been a Blake fan since high school. In Blake, Trump and the Road of Excess: An Urban Legend posted in The Millions by Jennifer Davis Michael I read that Trump had “framed on the wall of the library in his Trump International Hotel & Tower overlooking Central Park: ‘The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom;’ / ’You never know what is enough unless you know what is more than enough.’” Alas, it isn’t true as Ms. Michael adequately proves with a bit of clever research.

Of course, even if it isn’t Trump’s, the appropriation of the proverb in a luxury Manhattan condo is still worthy of comment. Roads of excess indeed lead to palaces, and if Blake’s professional readers (mostly academics who wear their genteel poverty as a badge of honor) are uncomfortable with the deployment of the proverb, it is entirely Blakean to shatter our sense of propriety; Blake’s proverbs are all about overturning conventional notions of respectability. Yet Trump is now a frontrunner in a presidential campaign, and these same Blakean proverbs are used in a February 2016 article explaining, and in part justifying, his ascendancy.

In this campaign, candidates’ language has come under intense media scrutiny, as it should. One commentator in 2015 described the election rhetoric so far as “unnervingly free of thought.” Sarah Palin’s endorsement of Trump was itself a baffling verbal exercise, compared to “performance art…even slam poetry.” In such a climate, when Facebook memes daily attribute words to people (living and dead) who never said them, it is incumbent on scholars — on all of us — to read responsibly, to distinguish between truth and what Stephen Colbert calls “truthiness,” even when the latter would better fit the story we want to tell. As Blake said elsewhere, “He who will not defend Truth, may be compelled to defend a Lie.” [Quote from The Millions]

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Jack Haye and James Maxwell artists

Okay, enough literary speculations, similes, metaphors, whatever. It’s time to take Karl Marx at his word:

“The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it.” Karl Marx, Eleven Theses on Feuerbach

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Jack Haye artist

The first thing that popped into my head when I decided to write about Trompudo, A Literary Phenomena was The Plague by Albert Camus. I went back to review some of the phrases I marked when I read the book years ago. I posted some of them below. The Plague holds the key to Trompudo. He is evil like Camus’ plague is evil. Like Dr. Rieux and his friends, we must fight against everything he stands for relentlessly. IMHO

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Jack Haye artist

[All qultes from: Camus, Albert; EbookEden.com (2009-10-16). The Plague (p. 225). EbookEden.com. Kindle Edition.]

Our citizens work hard, but solely with the object of getting rich. Their chief interest is in commerce, and their chief aim in life is, as they call it, “doing business.”

There have been as many plagues as wars in history; yet always plagues and wars take people equally by surprise.

When a war breaks out, people say: “It’s too stupid; it can’t last long.” But though a war may well be “too stupid,” that doesn’t prevent its lasting. Stupidity has a knack of getting its way; as we should see if we were not always so much wrapped up in ourselves.

But the plague forced inactivity on them, limiting their movements to the same dull round inside the town, and throwing them, day after day, on the illusive solace of their memories.

Naturally the picture-houses benefited by the situation and made money hand over fist.

And, to tell the truth, there was much heavy drinking. One of the cafes had the brilliant idea of putting up a slogan: “The best protection against infection is a bottle of good wine,” which confirmed an already prevalent opinion that alcohol is a safeguard against infectious disease.

“Calamity has come on you, my brethren, and, my brethren, you deserved it”

On the whole, men are more good than bad; that, however, isn’t the real point. But they are more or less ignorant, and it is this that we call vice or virtue; the most incorrigible vice being that of an ignorance that fancies it knows everything and therefore claims for itself the right to kill. The soul of the murderer is blind; and there can be no true goodness nor true love.

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, artist RTS

The Priest, Paneloux, whom I initially disliked transformed into a kind of hero for me even though I found his biblical acceptance of the plague disgusting. He became what we must become, the one who stayed.

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

I quote at length from Father Paneloux’s sermon because he speaks for Camus in making one of the most important points of the novel:

But, Paneloux continued, there were other precedents of which he would now remind them. If the chronicles of the Black Death at Marseille were to be trusted, only four of the eighty-one monks in the Mercy Monastery survived the epidemic. And of these four three took to flight. Thus far the chronicler, and it was not his task to tell us more than the bare facts. But when he read that chronicle, Father Paneloux had found his thoughts fixed on that monk who stayed on by himself, despite the death of his seventy-seven companions, and, above all, despite the example of his three brothers who had fled. And, bringing down his fist on the edge of the pulpit, Father Paneloux cried in a ringing voice:

“My brothers, each one of us must be the one who stays!” There was no question of not taking precautions or failing to comply with the orders wisely promulgated for the public weal in the disorders of a pestilence. Nor should we listen to certain moralists who told us to sink on our knees and give up the struggle. No, we should go forward, groping our way through the darkness, stumbling perhaps at times, and try to do what good lay in our power. As for the rest, we must hold fast, trusting in the divine goodness, even as to the deaths of little children, and not seeking personal respite.

The heroes are the ones who stay, like Tarrou who explains why he stays to Dr. Rieux. Tarrou ultimately dies for a town in which he arrived as a stranger.

“… this epidemic has taught me nothing new, except that I must fight it at your side. I know positively, yes, Rieux, I can say I know the world inside out, as you may see, that each of us has the plague within him; no one, no one on earth is free from it. And I know, too, that we must keep endless watch on ourselves lest in a careless moment we breathe in somebody’s face and fasten the infection on him.”

… The good man, the man who infects hardly anyone, is the man who has the fewest lapses of attention. And it needs tremendous will-power, a never ending tension of the mind, to avoid such lapses.

When something arrives to turn your world upside down, the easiest thing to do for those who have the means is to turn away. There is a phrase that cuts like a sword. It has been offered to those of us who are appalled by what we see so that we can impale ourselves. That phrase is: “Get over it.” Well, I refuse. Like Father Paneloux, Tarrou, Dr. Rieux, and Rambert, like Camus himself, I refuse to give in to what I perceive as a gross error. I refuse Huxley’s “soma”.

“..there is always soma, delicious soma, half a gramme for a half-holiday, a gramme for a week-end, two grammes for a trip to the gorgeous East, three for a dark eternity on the moon…” Aldous Huxley Brave New World

The philosopher Walter Kauifmann called partaking of the “soma” would an “impious crime” in The Faith of a Heretic.

… I am so far quite unable to justify one of my central convictions: that, even if it were possible to make all men happy by an operation or a drug that would stultify their development, this would somehow be an impious crime. This conviction is ultimately rooted in the Mosaic challenge: “You shall be holy; for I the Lord your God am holy.”

The heroes are the ones who stay, who fight at great personal cost, Father Paneloux, Tarrou, and the journalist Rambert who has a chance to leave but decides to stay and pleads with Dr. Rieux to be allowed to help. Rambert is a journalist stranded in Oran when the plague breaks out. He wants to leave to be with his fiancee but the town has been quarantined. At great difficulty and expense, he finds a way out. But then, in a supreme moral act of courage, he decides he must stay.

“Doctor,” Rambert said, “I’m not going. I want to stay with you.”

Tarrou made no movement; he went on driving. Rieux seemed unable to shake off his fatigue.

“And what about her?” His voice was hardly audible.

Rambert said he’d thought it over very carefully, and his views hadn’t changed, but if he

went away, he would feel ashamed of himself, and that would embarrass his relations with the woman he loved.

Showing more animation, Rieux told him that was sheer nonsense; there was nothing shameful in preferring happiness.

“Certainly,” Rambert replied. “But it may be shameful to be happy by oneself.”

Tarrou, who had not spoken so far, now remarked, without turning his head, that if Rambert wished to take a share in other people’s unhappiness, he’d have no time left for happiness. So the choice had to be made.

“That’s not it,” Rambert rejoined. “Until now I always felt a stranger in this town, and that I’d

no concern with you people. But now that I’ve seen what I have seen, I know that I belong here whether I want it or not. This business is everybody’s business.”

When there was no reply from either of the others, Rambert seemed to grow annoyed.

“But you know that as well as I do, damn it! Or else what are you up to in that hospital of yours? Have you made a definite choice and turned down happiness?”

Rieux and Tarrou still said nothing, and the silence lasted until they were at the doctor’s home. Then Rambert repeated his last question in a yet more emphatic tone. Only then Rieux turned toward him, raising himself with an effort from the cushion.

“Forgive me, Rambert, only, well, I simply don’t know. But stay with us if you want to.”

A swerve of the car made him break off. Then, looking straight in front of him, he said:

“For nothing in the world is it worth turning one’s back on what one loves. Yet that is what I’m doing, though why I do not know.”

He sank back on the cushion.

“That’s how it is,” he added wearily, “and there’s nothing to be done about it. So let’s recognize the fact and draw the conclusions.”

“What conclusions?”

“Ah,” Rieux said, “a man can’t cure and know at the same time. So let’s cure as quickly as we can. That’s the more urgent job.”

[Camus, Albert; EbookEden.com (2009-10-16). The Plague (p. 208). EbookEden.com. Kindle Edition.]

That’s what my reading of the literature tells me about Trompudo. Refuse, stay, rebel. There is a way out but not the cowardly way, not the easy way. It is such fights that make life worth living.

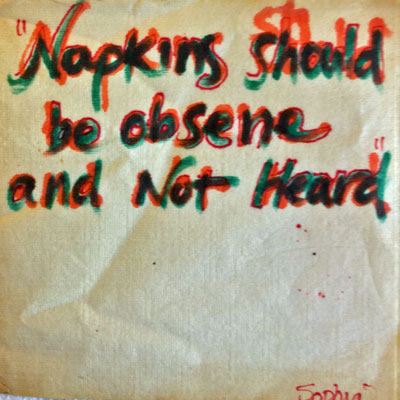

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Sophia artist

The Trump Presidency/Era…..it’s why God created alcohol…….

Good hearing from you, David, but

This philosophical stuff has done my poor brain in.

I’m still back at square one:

He wont submit his tax returns.

And we haven’ t seen his Birth Certificate.

Or Melania’s immigration papers or her prenup.

Watched an hour-long “Frontline” last night, an intensive, revealing examination of Trump’s life, which surely has him writhing and hissing. Showed how one of his main mentors was Roy M. Cohn, described details of domestic violence with his first two wives, went into his famous bankruptcy and more. Highly recommended.

Malignant narcissist.