“Cruelty to animals will get you punished, but cruelty to humans will get you promoted.” (as one of Brit’s friends said to her at the immigrant detention center where she worked in Ali Smith’s SPRING)

In a previous blog I explored Ali Smith’s Autumn, the first of her seasonta novels conceived “… as a series of books which we publish really close to the time of their writing – a kind of keeping the novel novel project – returning it to the notion of ‘the new.” I use the term seasonata because Smith’s series of books organized by the seasons plays inside my head like a sonata, in this case a sonata of four movements separate but related. After Autumn comes Winter.

Scottish Countryside 1974 near Banff

Grace Paley says it best: Everyone, real or invented, deserves the open destiny of life. Right now in such a divided and divisive world we need the human factor more than ever and we need to protect it, and honour it, and work for it as soon as someone or something suggests that one human being is worth less or worth more than another. The last time I saw John Berger speak, he defined fascism. He said fascism is what happens when one group of human beings thinks it has the right to decide about the worth of (or the superior rights of or the right to exclude) another group of human beings. I think this is bedrock for this Winter book. (Ali Smith On The Second In Her Seasonal Quartet)

After WINTER comes SPRING. I look forward to SUMMER, the final installment in her “seasonal quartet” slated to appear this August in the middle of a pandemic. Ali Smith has been “proclaimed … the best British or Irish novelist writing today.” If that doesn’t get your attention, perhaps the politics will. Each book in her “seasonal quartet” is infused with a rant focused on one or more symptoms of today’s toxic political atmosphere: fake news, lies, deception, global warming, immigrant bashing, populism in all its worst forms, the atrocities of white supremacists, globalization, Brexit etc. How does she write a novel (four novels) incorporating her passionate views on today’s politics without sounding preachy? By sounding preachy. Her novels are interspersed with riffs and asides and tangents sewed together like a complicated quilt that slowly reveals itself to those who have the patience to follow it through, who let themselves feel like one feels a sonata. “Somatize and the living is easy,” says Richard Lease’s (Doubledick’s) friend Paddy in SPRING. Each of the first three novels start with a rant.

Now what we don’t want is Facts. What we want is bewilderment … We want the people we call foreign to feel foreign we need to make it clear they can’t have rights unless we say so … What we want is outrage offence distraction. What we need is to say thinking is elite knowledge is elite what we need is people feeling left behind disenfranchised…” (SPRING)

Or:

God was dead: to begin with. And romance was dead. Chivalry was dead. Poetry, the novel, painting, they were all dead, and art was dead. Theatre and cinema were both dead. Literature was dead. The book was dead. Modernism, postmodernism, realism and surrealism were all dead. Jazz was dead, pop music, disco, rap, classical music, dead. Culture was dead. Decency, society, family values were dead. (WINTER)

Or:

It was the worst of times, it was the worst of times. Again. That’s the thing about things. They fall apart, always have, always will, it’s in their nature. (AUTUMN)

Train Through England 1974

The rant is an essential aspect of the Ali Smith style and if it puts you off, well, that’s the point. As opposed to the rant, Smith uses the pun to lighten and humorize as she moves along through each movement in her seasonata. “The Scottish writer Ali Smith is surely the most pun-besotted of contemporary novelists, edging out even Thomas Pynchon.” (James Wood, The New Yorker) Smith’s writing is unconventional to the extreme, something that makes it more difficult but also more rewarding to read her work.

… the Scottish marvel Ali Smith breaks rules better than anyone. She can build entire narratives around dreams and hallucinations. She can start a new novel in the middle of another. She can let a single exclamation point stand as an entire paragraph. It wouldn’t surprise me if she can write hanging upside down like a bat. And she’s given us, with “Spring,” the third in a planned quartet named for the seasons, an addition to a work-in-progress both as raw as this morning’s Twitter rant and as lasting and important as — and I say this neither lightly nor randomly — “Ulysses.” Rebecca Makkai, New York Times

A good book impacts me personally. I feel these three books (and probably SUMMER I hope) were written to me, for me and about me in some mysterious way. I say this as a self-described narcissist—like Paddy in SPRING who says when speaking about herself: “Let’s never do anything a demagogue narcissist might long for us to do.” Narcissism is nothing to be ashamed of. Paraphrasing one of Donald Trump’s heroes, Richard Nixon, “we are all narcissists now (Nixon was speaking of J.M. Keynes). Twitter, Facebook, etc. Si se puede.

Connections pop up wherever I look. Halfway through SPRING a voice from the ether announces “Berwick-upon-Tweed.” I was there! (Notice the photo at the top of this blog. I first wrote about my trip to Scotland HERE.) Just like Florence (the twelve year old magical child in the book) and Brit (Brittany the troubled protagonist), I went to Scotland on a train in 1974. Wow, what a coincidence! Yep. This book must be about me alright. It plays on my subconscious.

Scottish Countryside near Aberdeen

Scotland in the winter is bleak. I remember that distinctly. The four novels (at least the three I’ve read) of the Seasonal Quartet are bleak yet beautiful, funny, and engaging. They are also exhausting. So many connections. I try to chase down as many as I can. Connections inside, outside and between the books. Subtle but real.

I read closely, word by word, sentence by sentence, pondering each deceptively minor decision the writer had made. And though I can’t recall every source of inspiration and instruction, I can remember the novels and stories that seemed to me revelations: wells of beauty and pleasure that were also textbooks, courses of private lessons in the art of fiction. (Francine Prose)

I once audited an online class (the power of the Internet is not lost on Smith’s characters) from Amy Hungerford on the American Novel Since 1945. That’s where I learned “close reading”. You can read Ali Smith’s books quickly glossing over the connections or you can take your time. Either way, the books are a unique experience.

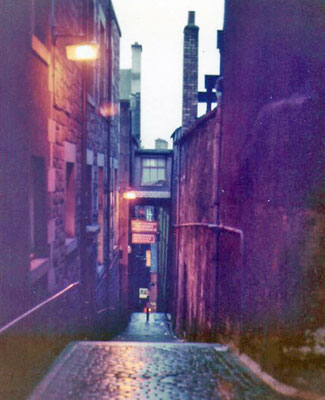

Edinburgh at night 1974

I’ll use this description of the three books by Jon Day, in the Financial Times since it quickly summarizes the books.

The first book in the series, Autumn (2016), which was hailed on publication as the great Brexit novel, and shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, followed the relationship between Elisabeth Demand, a precariously employed lecturer in art history at a London university, and her neighbour Daniel Gluck: a civilised old man who filled the emotional gap left by Elisabeth’s absent father, and introduced her to the horizon-expanding possibilities of art. (see my “review” HERE)

The second, Winter (2017), focused on Arthur, a frustrated nature-writer, and a brilliant, Cymbeline-quoting Croatian immigrant named Lux, whom Art had paid to pretend to be his girlfriend when he went home for Christmas.

The central characters of Spring are Richard Lease, a television film-maker who produced some memorable work in the 1970s and 1980s, now largely forgotten, and Brittany Hall, who works as a “DCO” (Detainee Custody Officer) in an “IRC” (Immigration Removal Centre — initialisms that suggest the euphemistic way institutions like these try to occlude what precisely goes on within them) called “the Wood”. The Wood is run by “SA4A”, the G4S-like service company whose operatives patrolled the fence that mysteriously popped up on some common land near Elisabeth’s house in Autumn, and for whom Art worked as a copyright infringement officer in Winter.

Flower Mart, London, 1974

Alex Calder: From Autumn to Spring, each text functions as a standalone novel while the interconnections of the series become more perceptible. For example, Daniel Gluck, the old man who enchants Elisabeth as a child with the possibilities of critical perception in Autumn, appears in the other texts in Seasonal. From a conversation in Autumn, we learn that Daniel “sold his old Barbara Hepworth piece of holy stone” (214). In Winter, Sophia, a retired entrepreneur hardened into a conservative worldview in contrast to her sister’s activism, recalls an impulsive, romantic holiday with an older man in Paris who has “a piece of [Hepworth’s] sculpture at his house” (251). His name is revealed as “Danny” (269), and the scene accords with Daniel’s memory in Autumn that he had been “in the middle of Paris in the 1980s” with “Sophie something” (Autumn 9-10). Additionally, a character resembling Daniel with a passion for Charlie Chaplin appears in Spring as an inspiration for a film by the radical screenwriter Paddy (59). These relations between the texts, among other significant plot points, suggest a continuity between the collage narratives of Seasonal and offer nuanced portrayals of characters of opposing worldviews.

The publisher’s description is short and succinct: Ali Smith’s Seasonal Quartet is a series of four stand-alone novels, separate but interconnected (as the seasons are), wide-ranging in timescale and light-footed through histories, which, when taken together, give us something more—all four united by the passing of time, the timing of narrative, and the endless familiarity yet renewal that the cycle of the seasons is. (Penguin Random House)

There is a pattern to the three books I’ve read. You might say a template. A young girl (Elizabeth in Autumn, Lux in Winter, Florence in Spring) causes (with her wit, innocence, yet profound understanding of life) some older folks (Daniel in Autumn, Sophia and Iris in Winter, Paddy and Richard and Brit in Spring) to rethink, reconsider, and relearn. Artists (Pauline Boty, Barbara Hepworth, Tacita Dean), authors (Shakespeare, Dickens, Katherine Mansfield, Rilke, etc), poets (Shelley) and even film stars like Charlie Chaplin form a sort of scaffolding around the central characters.

If you rise at dawn in a clear sky, and during the month of March, they say you can catch a bag of air so intoxicated with the essence of spring that when it is distilled and prepared, it will produce an oil of gold, remedy enough to heal all ailments Tacita Dean, A Bag Of Air

The twelve year old girl Florence in SPRING keeps her thoughts inside a notebook she calls her Hot Air Book. The book first surfaces as she and Brit travel by train across the border from England into Scotland.

She changes the subject. She taps the school notebook in the girl’s hand. Hot Air, Brit says. School thing. Not directly, the girl says. This is for what my, someone I know, gave me, because I sometimes have ideas and they thought I should write them down. The girl shows Brit, but only for a fraction of a second, a flash of the inside front page, at the top of which, under the underlined words Your Hot Air Book, someone has written the words RISE MY DAUGHTER ABOVE, with some lines of handwriting beneath. Can I look a bit more slowly at it? Brit says. No, the girl says. What else is written in it? Brit says. Hot air, the girl says. Private hot air. (SPRING)

The Hot Air Book resurfaces near the end of the novel.

Brit still has the Hot Air book, in fact she still has, in her wardrobe underneath the pile of jumpers, the schoolbag. There’s a pencil case in it too, full of pens of different colours. Some nights, when she’s not faffing about online, Brit reads things to herself out of the book, the funny pages, about realism, the foul things people really say or tweet. She has worked out, from how the girl has positioned them on the pages, that some of the pieces have been written to go together as if they are in sort of dialogues with each other, the right wing stuff answered by a voice bigger than it, the earth speaking, or time or her favourite season, and the story about the person with no face answering the ways people are used by the technology they think they’re the ones using, and the foul things people send people on twitter answered by the story of the girl who refuses the people who want her to dance herself to death. Brit quite often gets the book out specifically to read that villager story. But invariably she ends up feeling bad when she looks at the Hot Air book. One reason is that at the front, under the words RISE MY DAUGHTER ABOVE, a different older handwriting has written this: All through your life people will be ready and waiting to tell you that what you are speaking is a lot of hot air. This is because people like to put people down. But I want you to write your thoughts and ideas in this book, because then this book and what you write in it will help lift your feet off the ground and even to fly like you are a bird, since hot air rises and can not just carry us but help us rise above. This paragraph of handwriting really annoys Brit. Her mother never gave or made her a book like this one. Sometimes she thinks she could try to find the school. She could return the book in the schoolbag to the school and they will maybe have a forwarding address for it. The girl said she had a little brother. Brit wonders where he is too. Maybe she

could find him and give him the book to give to his sister. Vivunt spe. Or she could just burn the book and throw the schoolbag away. She doesn’t yet know which of these she’ll end up doing.

Train Station, York, England, 1974

In all of the Seasonal Quartet books thus far, Smith weaves separate stories full of surprises around each character. They intersect and separate as if in a dervish dance. Smith stays true to the Grace Haley quote: Everyone, real or invented, deserves the open destiny of life. Richard, Brit, and Florence connect for a time in SPRING but ultimately they disconnect to go their own way. Elisabeth and Daniel in AUTUMN have their time together, very valuable time, but Daniel dies into wherever death takes us and Elizabeth can’t follow. (There is a surprise in SPRING where we meet Elisabeth’s father, one novel opening into another.) Lux brings Art’s family together in WINTER then disappears when the job is done. That’s what I like most about these books, all of those lives that mingle and scatter, Hot Air Books that “help lift your feet off the ground and even to fly like you are a bird, since hot air rises and can not just carry us but help us rise above.” It’s good to know in the words of Ruby (AJ And The Queen):

“Nobody’s just one thing. People are more complex than that.” —Ruby

Little town by the sea, near Banff, Scotland, 1974