“Improvement makes straight roads; but the crooked roads without Improvement are the roads of genius.” William Blake

The lowly tanoak even when dying or dead elevates my mood. Literature is replete with the trope of the frightening forest. For example, Dante lost in his dark wood or Hawthorne’s Young Goodman Brown attending the devil’s forest party, innumerable fairy tales (Hansel and Gretel) and children’s stories (The Haunted Forest). Elizabeth Parker in The Forest and the EcoGothic: The Deep Dark Woods in the Popular Imagination offers the following Seven Theses in explanation: the forest is the imagined antithesis to civilization; the forest is bound to our fears of the past; the forest is a site of gruesome trial; the forest is the space in which we are lost; the forest is the space in which we are eaten; the forest is the manifestation of the human unconscious; and the forest is an antichristian environment.

While many perceive the woods as evil, others look to the woods for peace, tranquility, a relaxing and nourishing respite from urban angst, or as an ecological gift that needs to be protected and preserved. Yet others look at the forest as a resource to be managed for human benefit and economic advantage.

There is some truth in all these views. This is not going to be a political blog. I won’t take a stand either way. I have lived in the woods for nearly forty years, a privilege sadly unavailable to most. I’m no pioneer, no farmer, no ecologist nor woodsman nor even an astute observer, just a resident, an intruder, someone who appreciates the gifts of nature that surround me–gifts I know are undermined by my very presence, unfortunately. No doubt there are dangers in the woods though not many in my residential neighborhood. We have black bears, mountain lions, ticks, spiders, skunks, wood rats, insects that pack a powerful sting or bite, and a few other potentially harmful creatures. The most menacing animals are human beings ourselves: thieves, the psychologically deranged, overly zealous religious proselytizers, an occasional feisty neighbor, and those who haven’t a clue how to conduct themselves in the wild. On the other hand, I have enjoyed a steady stream of mostly harmless creatures who pass through our little patch of woods: deer, wild turkeys, ravens, red tailed hawks and songbirds galore, owls, bald eagles, squirrels and chipmunks, garden snakes, rabbits, foxes, banana slugs, snails, ants, the occasional possum, porcupine, and a multitude of beautiful insects that leave me alone if I leave them alone. Generations of osprey have nested in tall redwood snags next to our house. I see them every year sometimes carrying fish from the ocean up to their nests in the woods. I’ve also seen the rare Smith’s Blue or Lotus Blue butterfly once or twice over the years in our garden and an acorn woodpecker storing acorns in the holes it pecks into trees.

Goldenrod Crab Spider

Red-Veined Darter Moth

Skipper Moth

Living in the woods is not for everyone. Aside from those who want to live off the grid to hide their nefarious activities, there are those who value the solitude and independence and self-sufficient lifestyle. There are those who simply love the trees and want to live around them or at least visit them from time to time. Hermits are a category all their own who have been around since the beginning of time. No doubt, the forest attracts a wide variety of interesting characters.

Consider Walt Anderson. He settled near Sycamore Slough in Colusa County, California before the California gold rush began. He “had been all of his life a pioneer; and while he liked neighbors, he said he did not like to be crowded, and when settlers got within five or six miles of him he left for the mountains of Mendocino County.” He was a bear-hunter who boasted that “he ate no meat but bear meat.” He had a wife and family but had no interest in the society of other white people. So, “when Colusa was laid out, he considered the country too crowded, and moved westward into the mountains where there was more room.”

Blaze Foley was a country musician, songwriter and artist. His most famous song, If I Could Only Fly, was cut by Merle Haggard twice, once in a duet with Willie Nelson. Haggard called it “the best country song I’ve heard in fifteen years.”

Foley lived for a short while with Sybil Rosen in a tree house in the Georgia woods. Rosen wrote a book about her life with Foley: Living in the Woods in a Tree: Remembering Blaze Foley. In 2018 Ethan Hawke made the movie Blaze to celebrate the life of this nearly forgotten artist. It’s currently available on Netflix. Foley himself wrote a song about those times.

Christopher Thomas Knight was a very unusual hermit. … known as the North Pond Hermit, is a former recluse and burglar who lived without human contact (with two very brief exceptions) for 27 years between 1986 and 2013 in the North Pond of Maine’s Belgrade Lakes. Wikipedia

Knight’s story is told in The Stranger in the Woods: The Extraordinary Story of the Last True Hermit by Michael Finkel.

TreeGirl (Julianne Skai Arbor) hosts a website that “invites us to rebond with trees and the more-than-human world to live a life of re-enchantment, eco-literacy and soulful engagement, reminding us that we are nature. Using a remote control shutter release and tripod, TreeGirl captures herself and others intertwined with some of the most amazing trees all over the world to reveal that wild nature is where we belong–sometimes naked, sometimes vulnerable, in humility, with our shoes off and the wind blowing against our skin, ears open, listening to our lover, with all our heart and soul.”

Tanoak Lizard–Tanoak–Notholithocarpus densiflorus– California ©2012 TreeGirl

If you’re wondering what it’s like to live in the woods, there are books to read (14 Books like Walden to Imagine Life in the Woods) and plenty of online sites (see below) to visit.

“The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing that stands in the way. Some see nature all ridicule and deformity… and some scarce see nature at all. But to the eyes of the man of imagination, nature is imagination itself.” William Blake, letter to Reverend John Trusler

One of my favorite trees is our local tanoak. When my house was built back in 1978, I was thrilled to have a section of the floor made with local tanoak wood from Comptche. The wood is not easy to work with but the floor has held up well even after forty years of hard use.

The TreeGirl website provides a useful one-page summary on the tanoak. Here is a short excerpt.

Tanoak trees provide habitat and food for many animals, including black bears, northern flying squirrels, California ground squirrels, Allen’s chipmunks, dusky-footed wood rats, mice, mule deer, chipmunks, squirrels, raccoons, and foxes. Many birds seek food and shelter in these trees, such as woodpeckers, Steller’s jays, northern flickers, nuthatches, wild turkey, and varied thrush chickadees. TreeGirl

The Tanoak Tree: An Environmental History of a Pacific Coast Hardwood by Frederica Bowcut is a thorough study of how the tanoak, a food staple for native Americans and many birds and animals, was ravaged first in the 19th century by those who extracted the tannin, useful in tanning leather, from the bark of the tanoak almost driving the tree to extinction, then by herbicides used by forest companies to eradicate the oak trees that were considered weeds slowing the growth of higher profit softwoods, and recently by a combination of global warming and a disease known as sudden oak death. Yet, the tree is still here.

The tanoak offers a unique aesthetic value in the twists and turns and gnarls it undertakes when it eschews the option of straight tall growth. The wood is prized for furniture, flooring and even baseball bats.

One late nineteenth-century writer for a San Francisco newspaper compared old-growth tanoak groves in Mendocino County to Druidic temples because of their lofty branches and pleasing forms, a romantic reference to the lost sacred oak groves used in the ancient Celtic religion of the British Isles and Europe. Bowcutt

Out of all the available oaks and oaklike nut trees, tanoak acorns are some of the most relished and prized among the tribes of northern California. Frank Kanawha Lake

Several interesting and amusing myths surround the tanoak.

The Acorn Maiden

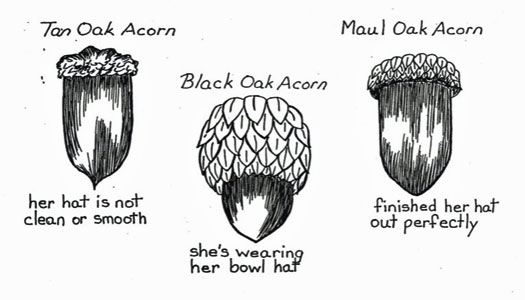

Once acorns were Ikareyavs (Spirit people). Then they told them: “Ye are going to go, ye must all have nice hats, ye must weave them.” Then they started in to weave their hats. They said: “Ye must all wear good-looking hats.” Then all at once they told them suddenly: “Ye would better go! Human is being raised.”

Black Oak Acorn did not finish her hat. She picked up her big bowl basket.

And Tan Oak Acorn did not clean her had [did not clean off the projecting straws from the inside]. She just wore it, she turned it wrong side out. She finished it.

But Post Oak Acorn just finished her hat out good. She cleaned it. Then Tan Oak Acorn said: “Would that I be the best acorn soup, though my hat is not cleaned!”

Then the went. They spilled [from the Heavens] into Human’s place. Then they said: “Human will spoon us uip.” They were Ikxareyavs too, they were Heavenly Ikxareyavs. The shut their eyes and then they turned their faces into their hats when they came to this earth here. That is the way the Acorns did. Tan Oak Acorn wished bad luck toward Post Oak Acorn and Maul Oak Acorn, just because they had nice hats. She was jealous of them. They wished her to be black. Nobody likes to eat Post Oak Acorn. And Maul Oak Acorn does not taste good either, and is hard. They [Post Oak Acorn and Maul Oak Acorn] do not taste good, [their] soups are black. And Maul Oak Acorn is hard to pound.

They were all painted when they first spilled down. Black Oak Acorn was striped. When one picks it up on the ground it is still striped nowadays. It is still striped. She was striped all over, that girl was. But Tan Oak Acorn did not paint herself much, becuase she was mad, because “my hat is not finished.”

When they spilled down, they turned their faces into their hats. And nowadays they still have their faces inside their hats.

The Tale of Tannin the Tanoak

Tanoak is thought to be a taxonomic bridge between oaks and chestnuts. Its fruit is an acorn, but with a spiny cap like a chestnut. After the 2002 Biscuit Fire, the old tanoaks started falling, and the old ones started growing, consuming trails.

So in 2009, before the Club incorporated, we were clipping it out along the Upper Chetco River, on Bailey Mtn Trail No 1109 just north of Blake’s Bar. Here it had grown so fast and furiously that the trail was unrecognizable.

That year, one volunteer, Tannin, got lost in a brush field of tanoak. Tannin was 23 or 24, he had high cheek bones and these big, bright, bulbous eyes. He kept clipping while the rest of the crew ate lunch.

“Tannin, come on, it’s lunch time,” I cried. But Tannin didn’t show up.

After a couple of hours, we launched a search. Night fell. The next day we searched high and low. But Tannin was gone, lost in the tanoak.

The Club in its infancy, afraid that a lost volunteer would mark the end of our career, decided to leave Tannin out there. The decision weighed on our consciences over the years. We celebrate the fact we have had no accidents. But we never told the truth about losing Tannin.

Last spring I started having dreams about Tannin. What had happened to him? Was Tannin dead? Later that summer we learned he was not.

Over the years, the section where Tannin was lost had grown in with tanoak again. As we worked there, my conscience weighed even heavier. I’d leave the group periodically, in search for Tannin’s skeleton, which I was convinced was somewhere near.

“What’s wrong, Gabe?” one volunteer asked as I returned to work.

“Oh, nothin, just–. Oh it’s nothin,” I responded, nervously. “Don’t leave the trail. People get lost out here.” I could see my volunteers eyeing me strangely.

Later that night, camping at Blake’s Bar on the Chetco,we heard some stomping around.

“Maybe it’s a bear,” said Angie Caschera. Its steps grew closer. We could tell it was big.

We shined our lights across the river, revealing movement in the brush. It was huge, whatever it was. Suddenly the beast appeared — half man, half plant.

It was 15 feet tall, with branches protruding in all directions. Two of the branches were large, four inches in diameter, and at the end of them were long-armed loppers. Its head looked like a giant tanoak acorn, but with a mouth, ears and eyes — big, bright, bulbous eyes.

High, pronounced cheek bones shined through. The beast was Tannin.

He jumped across the river, crashed into our campsite. I looked down, ashamed of our decision years earlier. What had happened? Tannin explained.

“That day, back in 2008, I can’t believe you left me here, Gabe,” he said.

I told him how sorry I was, and how the decision had haunted me over the years. “What happened that day, anyway?”

“That day, when I was clipping and pruning all the tanoak, I was breathing in the dust. It caked the inside of my mouth, tickled my throat, and I started coughing hard, so hard that I passed out. When I woke up after a couple days, I went back to camp and you guys were gone!”

“I’M SO SORRY, TANNIN!” I interrupted, but I could tell he was eager to continue on.

“I couldn’t find anything to eat out here, so I started eating tanoak acorns. After a few weeks, my fingers turned into tanoak sprouts, intertwined with the only tools I had, long-armed loppers.” He lifted his left limb, revealing the clippers. “I made my way through the brush-fields, clipping the tanoak. That winter, after you left me here–“

“I’M SO SORRY,” I sobbed.

“By the end of the winter I had been completely consumed and transformed by the tanoak,” he went on.

“Tannin, come back with us please,” I pleaded. “We’ll get you cleaned up, clip away all those spindly branches, treat you to a real meal.” I wanted to bad to make things right.

“This is my home now, in the brush fields.”

So we left Tannin out there again. Half-man, half plant, Tannin the tanoak, still lives along the Upper Chetco River.

The moral of this story is to always wear a bandanna over your face when working in the tanoak brush fields. Or you could end up like Tannin.

… evolution did not intend trees to grow singly. Far more than ourselves they are social creatures, and no more natural as isolated specimens than man is as a marooned sailor or a hermit. Their society in turn creates or supports other societies of plants, insects, birds, mammals, micro-organisms; all of which we may choose to isolate and section off, but which remain no less the ideal entity, or whole experience, of the wood—and indeed are still so seen by most of primitive mankind. John Fowles, The Tree

Let’s face it, the way we interact with the forest is full of contradictions. If you live in the woods, if you live in a home constructed of wood with a wooden deck and wooden furniture, if you use toilet paper or paper towels, read paper books or newspapers, write on paper, etc etc, then you are a consumer of wood products. Wood can be burned for heat, wood and organic waste can be transformed into biofuel for a source of energy, woodchips can be used in the garden, on and on. The forest provides habitat for innumerable animals, birds, and insects. It also provides the fuel for catastrophic forest fires. How to manage the forest, it’s complicated. In the meantime, enjoy the lowly tanoak or whatever forest trees or creatures you are lucky enough to see. I do, every day.

Tanoak Links

There are hundreds (thousands) of books, articles, links on the tanoak, even more on forests. Here are a few I like.

The Tanoak Tree, An Environmental History, Frederika Bowcut

Acorn Woodpecker – This Bird is Nuts

Traditional and Modern Methods of Acorn Preparation, Emily Moskal

Into The Woods, Myth & Moor, Terri Windling

The Forbidden Forest Trope, Shelby Ellis

Is Reintroducing Acorns into the Human Diet a Nutty Idea: Dawn Starin