This life’s dim windows of the soul

Distorts the heavens from pole to pole

And leads you to believe a lie

When you see with, not through, the eye.

William Blake, The Everlasting Gospel

Adriana Díaz Enciso is a Mexican poet, essayist, translator and writer. I came across her recent novel Ciudad doliente de Dios (Doleful City of God) by accident while reading about William Blake, something I am prone to do. Blake, as you know if you’ve followed Think in the Morning is one of the inspirations for this blog. I’ve been enthralled with Blake since high school when I wrote a report on him for an English teacher who changed my life as only a good teacher can. Enthralled even though I am often unable to understand him.

Reading any novel is a commitment. In this case, for me, the commitment is doubly large. The novel, over 700 pages, is only available in Spanish, a language I can read marginally at best. At age 67 years, William Blake taught himself medieval Italian in preparation for illustrating Dante’s Divine Comedy. While I have no intention of illustrating Enciso’s novel (as if I could), what I’ve read about the novel makes it irresistible.

Mental things are alone Real

William Blake

To understand Blake you must enter his mind. He gives you two paths, his poetry and his art (etchings, drawings, paintings). Enciso uses both and more, her own genius, to create her novel.

It is not only my interest in Blake that has led me to make this commitment but also my love of Mexico, the people, the culture, and hopefully some day the language. Artists all over the world have been inspired by Blake. Two of my favorite Mexican artists come to mind.

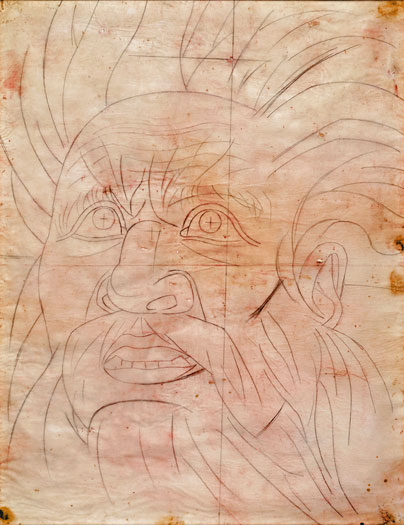

The Epic of American Civilization, [Jose Clemente] Orozco’s massive mural program in the library at Dartmouth College, likely owes a structural debt to William Blake. Jacquelynn Baas related several of Orozco’s narrative panels to Blake’s illustrated books America: A Prophecy, 1793 and Europe: A Prophecy, 1794, including The Departure of Quetzalcoatl, which is represented in the Wornick collection by a working drawing for Quetzalcoatl’s head. This wrathful Quetzalcoatl, who could pass for any angry Old Testament prophet, is perhaps Orozco’s most Blake-ean figure.

Figure Drawings From A Fiery Genius, Ruben C. Cordova

Quetzalcoatl’s head, Jose Clemente Orozco

… I drew in school. I was 9 or 10. We saw the images of Orozco and Rivera. I liked to make drawings on the walls. My mother didn’t like it, but my father resisted her! And in Oaxaca I discovered a school of fine arts near La Soledad”—Basílica de la Soledad—“The library had books with William Blake images. I loved them, even though I couldn’t read the poems.

Francisco Toledo

No me deja solo, Francisco Toledo

I’m lucky to have seen Orozco’s work in Guadalajara and Toledo’s work in Oaxaca and some of Blake’s work at the Tate in London. Now I can read the Doleful City of God to tie these works together.

The easiest way into Enciso’s novel is to visit her website were you will find interviews, reviews, posts, comments and even two short chapters translated to English. Click on the blue link: Adriana Diaz Enciso

[The comments in italics below are translated from an interview available on the website.]

The Doleful City of God starts from the question of whether it is possible to redeem human pain. Enciso addresses this question in her novel using the Prophetic Poems of William Blake. The title is from Saint Augustine’s City of God. Enciso adds “doleful” or “suffering” to the title to distinguish Blake from Augustine.

Certainly, for St. Augustine, the worldly city of men and the holy city touch, and on that Blake agreed … St. Augustine spoke from his authority as Doctor of the Church, with an inevitable emphasis on the notion of sin and punishment. Blake didn’t like that at all, he had his pretty radical ideas about what true religion was, and the idea of punishment put him in a terrible mood.

Blake was a man of his world and time but his artistic genius was unique and timeless.

Blake paid close attention to the social and political events of his time, and denounced all injustice and all oppression. However, he knew that there was a transcendent dimension in all this, which was not limited to the political or to the conjuncture of a specific historical moment.

As an artist, Blake embodies the utmost freedom, never giving in to the social pressures or the artistic and literary conventions of his time, true only to his vision, and that is what, ideally, I [Enciso] would like to do with my writing. It is also an ideal of life. For Blake, art and life were not divisible. His spiritual freedom despite the immense obstacles he encountered in his life, his integrity as a man and as a poet, as an artist, have been a source of immense inspiration for me, and also of encouragement when the soul falters.

The interviewer asks Enciso this important question: In the novel you mix religion and political facts, what do you think will save man, politics or spirituality? Or do you prefer to think of art as a saving instance?

It is a huge question, which has no answer but that humans ask ourselves over and over again. It is something we must keep asking ourselves. What will save man? Is there, in fact, something we can call salvation? I do not know. I am very sure that politics, by itself, does not save anyone, but neither can the spiritual dimension of life exist with its back to reality. A spirituality that closes its eyes to the suffering of the world is not really spirituality, but escapism. Like Blake, I see a way in art, but I think that talking about a way to save is too much to ask. It is a way to open the senses and consciousness, to awaken our sensitivity, to remind us that there is a dimension in the human soul that transcends the limitations of our historical and temporal perspective. If it is salvation, it is so in a measure that is both humble and powerful: that of our own humanity. But humans are going to keep looking, and making mistakes.

Enciso describes how Blake maneuvers between art and politics, reality and imagination.

Blake manages in his Prophetic Poems to talk about social injustice in England in his time, about the French Revolution and the liberation of America, but he does so by integrating these realities into his cosmogony, giving them a mythical dimension, and therefore beyond the limited temporal conjuncture. That seems great to me, the thorough understanding of the delicate balance between our perception of the temporal and the eternal. And he certainly wanted to abolish all temporary injustice and oppression as well. But art cannot by itself solve political problems, nor is it its role. It does affect our consciousness, and in this sense it can become one of the many agents of change, within a broader context. Its influence is then subtle but, again, powerful; it is a matter of complex interconnections with the other aspects of our social being. I believe that when art tries to become a political instrument, it dies as art, it becomes propaganda, and it withers away. Politics alone is not the solution either; a political movement also has to be open to those subtle connections with all the dimensions of the human of which I speak. If it does not become dogma and culminate in another form of oppression, which Blake knew very well, and which we unfortunately see repeated over and over again in history.

Enciso’s comments above bring to mind Charles Peguy (Temporal and Eternal) whom Think in the Morning discussed briefly in a prior blog.

When asked how different generations handle “the delicate balance between our perception of the temporal and the eternal,” Enciso responds:

In some way, youth embodies the agent of change in all generations, although not exclusively, but that is part of what it means to be young. Being young, seeing the injustices of the world and doing nothing is like being dead.

About the sacrifices she made over the 21 years it took to write the book, she offers the following credo which many artists will recognize as true.

… how we react to adversity is more important than adversity itself. If we persevere, if we stay true to our vision, we will be achieving a victory that, true, does not occur in the mundane dimension and does not pay the rent, but it has more value because it is not just a personal victory, but a human one. Art remains, for others; it is an act of communion. When I despair I think of Blake – among so many others – and that often helps me regain my equanimity.

The author says her novel is neither realism nor fantasy but the world she describes is “absolutely real” to her.

Reality and imagination are, in a way, the same. Imagination is the human faculty that allows us to perceive reality. Nothing separates them: our perception is the bridge, and when our perception is truly awake, it is very clear that there is no division between the perceiver, the act of perceiving and the perceived. We are part of reality, we must not forget it.

There is an interesting discussion about doubt in the interview that led me to review once again Jennifer Hecht’s wonderful book Doubt: A History.

We stop believing because human life is hard; because we are fragile and we often want tangible proof. Doubt is of course something very personal, but we cannot underestimate the effect of the society in which we live. If we live, for example, in a society like ours, consumerist, deliriously materialistic, pathologically hooked on distraction, indiscriminate consumption of information and almost forcing ourselves into alienation, we must have strength and discipline so as not to succumb to doubt. But then again, humans have always doubted, and sometimes doubt is good. Sometimes the light comes out of the deepest darkness.

Enciso’s answer to “what would the ideal sacred city be like?” is both beautiful and humble.

Oh, that’s what I tried to find out with the novel! I did not find the answer, as its characters did not find it. But Ahania, in the novel, sees very clearly that the sacred city is neither ideal nor perfect: that it also contains pain. The characters are confused, as I am, but there is a conviction, a bittersweet finding: the ideal city is this: London, Mexico City, St. Augustine’s Rome, any city anywhere in the world, with all its violence and pain and ugliness. There is the holy city. Only there, and that is where we will find it.

The full interview and other materials available on the author’s website convinced me to read the book, all 700 plus pages in Spanish. I’m just starting and it may take years but I have no doubt about the worth of the project. Of course, I am a Blake fan and a lover of Mexico but even if I were not I suspect I would be tempted to read the book anyway. Of course, whether you read it is up to you but I strongly recommend you at least take a look.

Reading, reading your words I am led to Picasso and Guernica

and how he, as well, maneuvers between art and politics and of course, reality and imagination. Thank you.

“A spirituality that closes its eyes to the suffering of the world is not really spirituality, but escapism.” – great line there, David! I concur.

“A spirituality that closes its eyes to the suffering of the world is not really spirituality, but escapism.” – Great line there, David. I concur