To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour

William Blake, Auguries of Innocence

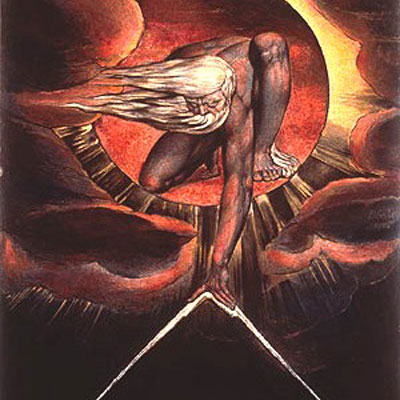

William Blake, The Ancient of Days

Pierce High School in Arbuckle, California is not the kind of place you would expect a young boy to develop a life-long love for the eccentric mystical English poet William Blake. Two hundred students located in a rural agricultural setting, conservative, focused mainly on football, basketball, and baseball, Friday night dates, and summer jobs consisting mostly of helping with the harvest, changing sprinkler pipes, cutting weeds, knocking almonds and apricots then standing by the huller belt to remove the rocks and hulls—this was not an atmosphere conducive to poetry. But it was. It was because of one teacher I’ll never forget.

When Nancy Mock came to Pierce High School to teach English, she was my first experience with an albino—white hair and freckled skin, pink eyes requiring glasses thick and opaque as butterscotch buttons. She was rumored to be a lesbian but no one seemed to care. She introduced me to Shakespeare and Chaucer and that led me to Isak Dinesen long before Out of Africa was commercialized into a movie. I was also led to William Blake.

I chose Blake as the subject of my senior English paper. Having acquired my driver’s license a year earlier, I spread my new wings and drove from Arbuckle to Berkeley to visit the book stores along Telegraph and Durant. It was there I acquired my copy of Mark Schorer’s William Blake: The Politics of Vision, the first of many books by and about Blake I have been reading ever since.

Like Philip Pullman in his wonderful essay William Blake and Me, I was immediately and forever enthralled by everything and anything Blake. Not that I understood Blake then or that I understand him now. I didn’t and I don’t. But, like Pullman, I “perceived” something”, something I wanted and was willing to devote many hours to have.

Around the same time Nancy Mock came to Pierce High School, another teacher arrived that was to have an equally profound influence on me, a very different influence that shook me to the core, disturbing my mind in such a way that I’ve never been at peace since.

“Without contraries there is no progression.” William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

Dale Sherrill was Pierce High School’s poliomyelitic science and math teacher. He wore leg braces and metal crutches strapped to his arms as he inched his way down the hallway from his office to the classroom. He taught me Euclidean geometry, analytical geometry, calculus, and physics, subjects I adored because of the pristine certainty they provided. On the weekends, he and the band teacher, Verne Cowen, distilled a very powerful vodka. On a few occasions, I would visit their house with another math enthusiast and Mr. Sherrill would serve us an occasional Vodka Collins.

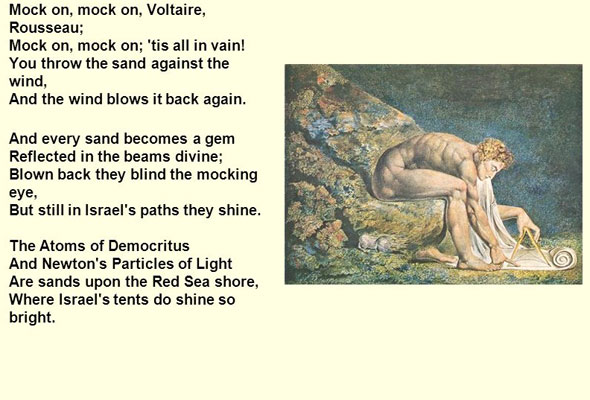

In those innocent years, thankfully there was nothing to suggest that my love of William Blake and science and math might be incompatible. I delighted in Blake’s An Island In the Moon knowing full well that it was a satire making fun of taking yourself or anyone (or anything) too seriously. I read Mock On, Mock On, Voltaire, Rousseau with a vague understanding that it was a warning about the limits of science. None of this bothered me at the time. In some inexplicable way I squared my love of Blake with my love of science.

William Blake, “Newton” measuring the world

And, I still do. Which is why I am so pleased with Sean Carroll’s new book The Big Picture: On the Origins of Life, Meaning, and the Universe Itself. It has made me think again about this strange love-hate relationship between science and art, truth and beauty, beauty and truth. I hope to write more when I finish reading Carroll’s book. I’m thinking a lot these days about my love of Blake and my love of science and how to make sense of the two at the same time. For now I will simply defer to Keats:

Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

….. Ode On A Grecian Urn, John Keats

Nice!

Thanks Gary, you should read chapter 47 in Carroll’s book. We had a discussion about this once …

You’re in good company, David–Herr Einstein was an art-and-science kind of guy, too! Any so-called contradictions between art (I mean, of course, “real” art, which I’m not going to try to define here) and science are specious and phony, designed to create ideological division!

Interesting, Nancy Mock was my junior high principal in Patterson, CA. I graduated from Patterson Junior High School in 1976, Nancy Mock was indeed a lesbian, as I always thought she might have been. She had a loud authoritative voice. She was a learned educator and had a great laugh. I’ll never forget her.

Thank you. I won’t forget her either.