Previously Discussed Literature On The 1918 Pandemic

Katherine Anne Porter: Pale Horse, Pale Rider

William Maxwell: They Came Like Swallows

This grey wall, unshaken, mighty, was the end of the long preparation, as it was the end of the sea. It was the reason for everything that had happened in his life for the last fifteen months. It was the reason why Tannhauser and the gentle Virginian, and so many others who had set out with him, were never to have any life at all, or even a soldier’s death. They were merely waste in a great enterprise, thrown overboard like rotten ropes. For them this kind release,—trees and a still shore and quiet water,—was never, never to be. How long would their bodies toss, he wondered, in that inhuman kingdom of darkness and unrest? Willa Cather, One Of Ours

The early reviews of Willa Cather’s One Of Ours were negative. The great Ernest Hemingway did not like it: “Look at One of Ours,” he wrote, complaining about the frivolity of the American reading public, “[Pulitzer] Prize, big sale, people taking it seriously. You were in the war weren’t you? Wasn’t that last scene in the lines wonderful? Do you know where it came from? The battle scene in Birth of a Nation. I identified episode after episode, Catherized. Poor woman she had to get her war experience somewhere.” (Quoted by John J. Murphy in One of Ours as American Naturalism, Great Plains Quarterly).

What her detractors missed was that the novel was not really meant to be a war novel. It was the (fictional) story of Cather’s “first cousin Grosvenor P. Cather, who had died in the World War I battle of Cantigny, France, in May 1918, along with 198 other U.S. troops. Grosvenor had a fascinatingly sensitive and rebellious temperament with which Cather felt a strong affinity. As she wrote in a letter to her aunt Frances Smith Cather, Grosvenor’s mother, on June 12, 1918, a few weeks after his death, “He was restless on a farm; perhaps he was born to throw all his energy into this crisis and to die among the first and bravest of his country.”(Caterina Bernardini, Not Even A Soldier’s Death, Lapham’s Quarterly).

It is a novel that prominently features the “Spanish flu” of 1918, something curiously avoided by most authors at the time and since. (Note, a new novel by Ellen Marie Wiseman-The Orphan Collector is due out in August. It is “a powerful tale of upheaval, resilience and hope set in Philadelphia during the 1918 Spanish Flu outbreak” according to one review.) One reason for the lack of writing on the 1918 pandemic was the law. The “wartime restrictions on communication:” misled and misinformed the public about the risks the country was facing.

World War I was still ongoing, and wartime restrictions on communication had deadly effects. There were limits on writing or publishing anything negative about the country, and posters asked the public to “report the man who spreads pessimistic stories.” In Philadelphia, doctors convinced reporters to write about the risk posed to the public by the Liberty Loan parade on September 28, which would gather thousands of people who could potentially spread the flu. Editors refused to run the stories, or any letters from the doctors. More than 20,000 Phildelphians later died of the flu. (Ellen Marie Wiseman, What 1918’s “Forgotten Pandemic” Can Teach Us About Today, Vanity Fair.)

In Book IV of the novel, The Voyage of the Anchises, Cather vividly describes the journey of Claude Wheeler together with twenty-five hundred American troops from New York to France. Like Katherine Anne Porter and William Maxwell, Willa Cather’s life split in two as a result of the pandemic and the Great War.

“A careful study of her later so-called —Nebraska novels’ reveals Cather’s growing disaffection with a world in which thoughtless and greedy men raped the land for profit,” wrote Mary R. Ryder. “For Cather, the world —broke in two in 1922 or thereabouts.'” (Such News Of The Land: U.S. Women Nature Writers, Thomas S. Edwards and Elizabeth A. De Wolfe)

According to Cather herself, “…One of Ours has more value to it in than any of the others. I don’t think it has as few faults as My Antonia or A Lost Lady, but any story of youth, struggle, and defeat can’t be as smooth in outline and perfect as just a portrait.” Pennsylvania Center For The Book: Cather

One of Ours (winner of the Pulitzer Prize in 1923) is about an existentially troubled Nebraska farm boy who decides that enlisting to fight in World War I will provide meaning in his life. The first three chapters (or Books as they are called) describe beautifully in Cather’s familiar way how it was to grow up on a prairie farm in Nebraska in the early 20ieth century. The final Book V catalogues Claude’s short wartime experiences. The focus of this blog is on Book IV: The Voyage of the Anchises. That is where Cather provides us observations on the influenza pandemic that ultimately killed over twice as many as were killed in the military battles.

There is a style change in Book IV that forebodes the darkness that is about to arrive sooner than expected.

A long train of crowded cars, the passengers all of the same sex, almost of the same age, all dressed and hatted alike, was slowly steaming through the green sea-meadows late on a summer afternoon. In the cars, incessant stretching of cramped legs, shifting of shoulders, striking of matches, passing of cigarettes, groans of boredom; occasionally concerted laughter about nothing. Suddenly the train stops short. Clipped heads and tanned faces pop out at every window. The boys begin to moan and shout; what is the matter now?

Twenty five hundred boys heading off to the Great War had no idea that a different kind of enemy was about to strike their ship. On the morning of the third day out “a sergeant brought Claude word that two of his men would have to report at sick-call. Corporal Tannhauser had had such an attack of nose-bleed during the night that the sergeant thought he might die before they got it stopped.”

The cramped conditions on board the Anchises helped spread the sickness from the moment it started much like on cruise ships, military ships, nursing homes, meat packing plants and large cities today. A short conversation between Claude and Doctor Trueman (the name seems intentionally descriptive of the doctor’s character) foreshadows the horrors to come.

“Is there an epidemic of some sort?”

“Well, I hope not.”

One of Claude’s roommates, Lieutenant Bird, is the first to die. He is buried at sunrise in a gruesome ceremony captured by Cather: “sewed up in a tarpaulin, with an eighteen pound shell at his feet.”

Things quickly get worse with dreadful rapidity. Cather depicts the death of Claude’s corporal, Fritz Tannhauser, a happy-go-lucky German American boy in tragic detail.

At eleven o’clock one of the Kansas men came to tell Claude that his Corporal was going fast. Big Tannhauser’s fever had left him, but so had everything else. He lay in a stupor. His congested eyeballs were rolled back in his head and only the yellowish whites were visible. His mouth was open and his tongue hung out at one side. From the end of the corridor Claude had heard the frightful sounds that came from his throat, sounds like violent vomiting, or the choking rattle of a man in strangulation, and, indeed, he was being strangled. One of the band boys brought Claude a camp chair, and said kindly, “He doesn’t suffer. It’s mechanical now. He’d go easier if he hadn’t so much vitality. The Doctor says he may have a few moments of consciousness just at the last, if you want to stay.” “I’ll go down and give my private patient his egg, and then I’ll come back.” Claude went away and returned, and sat dozing by the bed. After three o’clock the noise of struggle ceased; instantly the huge figure on the bed became again his good-natured corporal. The mouth closed, the glassy jellies were once more seeing, intelligent human eyes. The face lost its swollen, brutish look and was again the face of a friend. It was almost unbelievable that anything so far gone could come back. He looked up wistfully at his Lieutenant as if to ask him something. His eyes filled with tears, and he turned his head away a little. “Mein’ arme Mutter!” he whispered distinctly. A few moments later he died in perfect dignity, not struggling under torture, but consciously, it seemed to Claude,—like a brave boy giving back what was not his to keep.

From this point onward the deaths build up rapidly. The death list was steadily growing; and the worst of it was that patients died who were not very sick. Vigorous, clean-blooded young fellows of nineteen and twenty turned over and died because they had lost their courage, because other people were dying,—because death was in the air. The corridors of the vessel had the smell of death about them. Doctor Trueman said it was always so in an epidemic; patients died who, had they been isolated cases, would have recovered.

The reasons for the increasing deaths are misinterpreted by Claude who, like many people at the time, attributes them to a “loss of courage.” Cather was aware that, as observed by scholar Susan Kent, “the conditions of this war may well have enabled a common and usually mild disease to mutate into a deadly strain that spread like wildfire around the world…Environments with large concentrations of people enabled the virus to take hold [and] sufficient hosts—young, healthy men—were continuously made available, so that the virus could survive to reproduce.” Soldiers were perfect carriers for the infection—as Susan K. Kent explained, “In attacking the virus,…the cytokines also attacked vulnerable respiratory tissue, making those possessing the strongest immune systems the most likely to succumb to respiratory illness, particularly pneumonia.”

Claude recognizes the heartbreak of so many young men dying needlessly but he remains focused on what he deems the most important thing, moving ahead in his mission to find relevance in his military mission.

Only on that one day, the cold day of the Virginian’s funeral, when he was seasick, had he been really miserable. He must be heartless, certainly, not to be overwhelmed by the sufferings of his own men, his own friends—but he wasn’t. He had them on his mind and did all he could for them, but it seemed to him just now that he took a sort of satisfaction in that, too, and was somewhat vain of his usefulness to Doctor Trueman. A nice attitude! He awoke every morning with that sense of freedom and going forward, as if the world were growing bigger each day and he were growing with it. Other fellows were sick and dying, and that was terrible,—but he and the boat went on, and always on.

Cather recognizes the blunt absurdity and meaninglessness of the event and uses scenes and dialogue that strongly highlight the horrifying nature of having influenza on board a troop ship. Claude’s existential reflections make the reader think about the true worth and value of life. These young men, consumed and overcome by a mysterious and powerful epidemic and thrown into the sea, become an omen of sheer lack of meaning.

This novel, the first of those about the 1918 pandemic, fits in well with the earlier novels we’ve discussed. Porter considers how the pandemic affects the lives of two young adults just starting out in life. Maxwell delves into the family dynamics during the time of a pandemic. Cather focuses more on the philosophical implications of a pandemic.

I haven’t read much Willa Cather. I remember Paul’s Case, a short story I read years ago. It isn’t “pandemic literature” but there are some similarities to One Of Ours, Cather’s novel of pandemic and war.

Claude Wheeler is a young man disillusioned with a life he considers not “worth the trouble of getting up every morning.”

“One of his chief difficulties had always been that he could not make himself believe in the importance of making money or spending it. If that were all, then life was not worth the trouble.”

“He was a clumsy, awkward farmer boy, and even Mrs. Erlich seemed to think the farm the best place for him. Probably it was; but all the same he didn’t find this kind of life worth the trouble of getting up every morning.”

Claude found one thing to give life meaning.

Claude couldn’t resist occasionally dropping in at the Erlichs’ in the afternoon; then the boys were away, and he could have Mrs. Erlich to himself for half-an-hour. When she talked to him she taught him so much about life. He loved to hear her sing sentimental German songs as she worked; “Spinn, spinn, du Tochter mein.” He didn’t know why, but he simply adored it! Every time he went away from her he felt happy and full of kindness, and thought about beech woods and walled towns, or about Carl Schurz and the Romantic revolution.

When he realized he was not destined for that life of music and culture to which he aspired, that he was stuck in an unhappy marriage and a dead end career, he opted to enlist hoping to find something worth getting up every morning for. But, the war ultimately consumed all his mornings in one short moment.

The blood dripped down his coat, but he felt no weakness. He felt only one thing; that he commanded wonderful men. When David came up with the supports he might find them dead, but he would find them all there. They were there to stay until they were carried out to be buried. They were mortal, but they were unconquerable.

Paul (in Paul’s Case) was also enthralled by music and by the high arts.

“… he got what he wanted much more quickly from music; any sort of music, from an orchestra to a barrel organ. He needed only the spark, the indescribable thrill that made his imagination master of his senses, and he could make plots and pictures enough of his own … he was not stage-struck—not, at any rate, in the usual acceptation of that expression. He had no desire to become an actor, any more than he had to become a musician. He felt no necessity to do any of these things; what he wanted was to see, to be in the atmosphere, float on the wave of it, to be carried out, blue league after blue league, away from everything.”

Paul sacrificed his life for a few moments of glory knowing that in the end it is a losing game.

“The carnations in his coat were drooping with the cold, he noticed; all their red glory over. It occurred to him that all the flowers he had seen in the show windows that first night must have gone the same way, long before this. It was only one splendid breath they had, in spite of their brave mockery at the winter outside the glass. It was a losing game in the end, it seemed, this revolt against the homilies by which the world is run.”

Sadly, the pandemic of 1918 turned millions into Claude and Paul unwillingly, unknowingly, senselessly and for no reason other than the cruel randomness of the universe. Today we know more, have better tools to defend us, but are we willing to make the sacrifices necessary? Are we willing to share the costs at a time when inequality is at all time highs? Or, are we going to get bogged down in blaming others for or own failures? Are we going to help the least fortunate who bear the heaviest burden or are we going the use the occasion to further enrich those at the top?

Today there are very vocal groups of protesters unwilling to give up their “hard-earned” freedom for the greater good. It makes me wonder what future historians and storytellers will say about us when they look back at this time of COVID-19. Will they admire our willingness to rise to the occasion, or not? Will they realize we learned from the past or that we were destined to repeat it? Perhaps if more of us remembered 1918—the year of the “forgotten pandemic”—we’d beat back COVID-19 sooner rather than later. Ellen Marie Wiseman

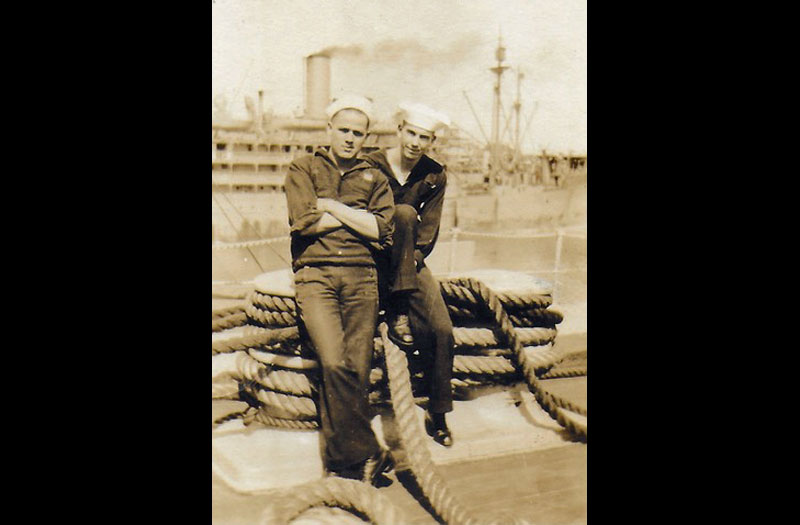

“A Fast Convoy” by Burnell Poole