There are some novels I’d like to read over and over again. Daniel Kehlmann’s novel “F” is such a book. Sadly, I don’t have the time although I did revisit it again to put this post together.

There are five major characters: Arthur Friedland (the father who says he’s immune to hypnosis but whose life is changed by it), Martin (the older son who becomes a Catholic priest in spite of not believing in God), Eric (a Bernie Madoff-like investment adviser fraudster), Ivan (Eric’s twin who paints forgeries) and Eric’s daughter Marie who pulls everything together. The book is an hilarious romping family saga sans females except for Marie. The “F” in the title contains anti-Whitmanesque multitudes: Friedland, family, failure, faith, fraud, future and most importantly fate.

“Fate,” said Arthur. “The capital letter F. But chance is a powerful force, and suddenly you acquire a Fate that was never assigned to you. Some kind of accidental fate. It happens in a flash.

Time is just one illusion that Kehlmann tackles in his comical, serious, sad, happy, reflective novel. Ivan gives us his version of Zeno’s Paradox:

The half of the distance still remaining will have its own half, and that half yet another one, and I grasp that time is not only endlessly long but also endlessly dense, between one moment and the next lie an infinite number of moments; how can they possibly pass?

Martin, the disbelieving priest gives us his take on time.

“Augustine’s theory of time goes back much further than the Aristotelian tradition,” I said. “Everyone quotes his remark that we know what time is as long as we don’t think about it. It’s beautiful, but as a theory of knowledge, it’s weak.”

And the author says in an interview:

“For example, my novel F is about how things can happen at the same time, and even if we don’t know it, they still influence each other. People interact but interpret their interactions in completely different ways. I describe a lunch between two brothers, told from the side of one brother. Then, much later in the book, I tell the other brother’s point of view, and it’s a completely different situation for him: all the assumptions of his brother—and the reader—were wrong.”

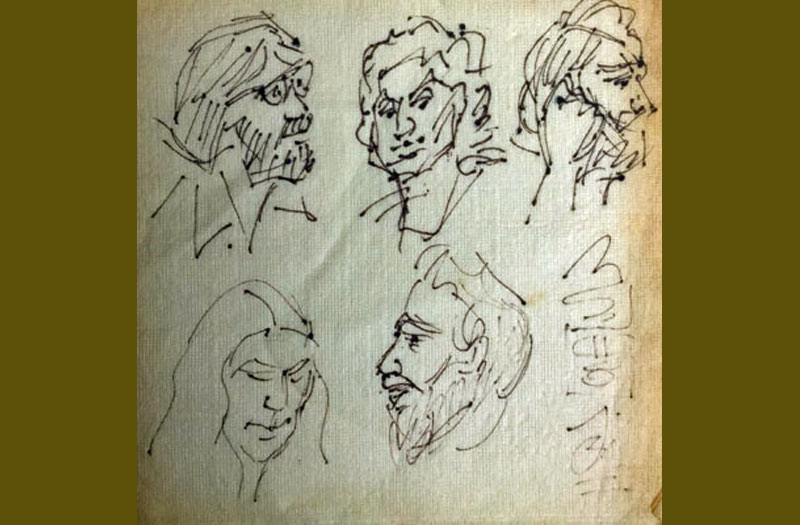

Meaning, or the lack of it, permeates the novel. Ivan ruminates about meaning while he paints his forgeries of Heinrich Eulenboeck

What if you could read the universe? Perhaps that’s what is behind the terrifying beauty of things: we are aware that something is speaking to us. We know the language. And yet we understand not one word.

Arthur introduces his granddaughter Marie to pointillism and she marvels at how it mimics life itself.

She stepped even closer, and immediately everything dissolved. There were no more people anymore, no more little flags, no anchor, no bent watch. There were just some tiny bright patches of color above the main deck. The white of the naked canvas shone through in several places, and even the ship was a mere assemblage of lines and dots. Where had it all gone? She stepped back and it all came together again: the ship, the portholes, the people, even though she’d just seen that none of it was even there. She took another step back, and now it seemed as if the picture were telling her that whatever it was communicating to her had nothing to do with what it was actually portraying. It was some kind of a diplomatic message that seemed to be contained within the brilliance of the light, the vast expanse of the water, or the distant trajectory of the ship itself.

There is so much time in a life, she can’t imagine what people do with it.

All the same, a day was a long time. So many days still until the holidays came around, so many more until Christmas, and so many years until you were grown up. Every one of them full of days and every day full of hours, and every hour a whole hour long. How could they all go by, how had old people ever managed to get old? What did you do with all that time?

She asks Arthur “Where do you live?”

Arthur: “I travel a lot.”

Marie: “Are you still writing?”

Arthur: “No.”

Marie: “Why didn’t you come before now?”

Arthur: “I have things to do.”

Marie: “What kinds of things?”

Arthur: “Nothing.”

Marie: “You do nothing?”

Arthur: “It isn’t that easy.”

Later, they stop at a Fair and Arthur continues his explanation.

“People will tell you life is all a matter of obligations. Maybe they’ve already told you. But it’s not always the case.”

Marie nodded. She had no idea what he meant, but she hoped he wouldn’t look at her and realize this.

“You can live without ever having a life. Without entanglements. Maybe it doesn’t make for happiness, but it takes the load off.”

After some adventures at a Fair including a meeting with a fortune teller, Arthur tries to explain his life to Marie.

Arthur: “I have a house,” he said as they drove off. “It’s by a little lake, and there isn’t another house to be seen in any direction. When I’m there, I can work all day. It rains a lot. I thought nature would do me good, but that was before I knew that nature mostly consists of rain. Sometimes I take a trip somewhere, and then I come back again. For a long time my work was a cut above average, then it wasn’t anymore, and now all I do is read other people’s books. Books that are so good, I could never have written them myself. You asked what I do—well, that’s what I do.”

Marie: “That’s how you spent all your time?”

Arthur: “It went quickly.”

Marie and her grandfather leave the Fair before the fortune teller tells her what her future will be and she is disappointed. She complains to her grandfather.

“But my future!”

Arthur responds:

“Seek it out yourself. Seek out the one you want.”

Dreams appear throughout the novel. One of Martin’s friends explains hell as a dream.

We really visit hell at night during those moments of truth we call nightmares. Whatever hell may be, sleep is the gateway through which it forces its entry. Everyone knows hell, because everyone is there every night. Eternal punishment is simply a dream from which there is no awakening.

The patriarch of this strange family, Arthur Friedland, becomes famous for a novel (My Name Is No One) in which the very idea of a self is obliterated.

Is My Name Is No One a merry experiment and thus the pure product of a playful spirit, or is it a malevolent attack on the soul of every person who reads it? No one knows for sure, maybe both are true.

But there is a sense that no sentence means merely what it says, that the story is observing its own progress, and that in truth the protagonist is not the central figure: the central figure is the reader, who is all too complicit in the unfolding of events.

Very slowly there comes a dawning sense of comprehension, then the realization of being on the brink, and then the story breaks off—just like that, without warning, right in the middle of a sentence.

The second half is about something else. Namely that you, yes, you, and this is no rhetorical trope, you don’t exist. You think you’re reading this? Of course you do. But nobody’s reading this.

The world is not the way it seems. There are no colors, there are wavelengths, there are no sounds, there are vibrations in the air, and actually there is no air, there are chains of atoms in space, and “atoms” is just an expression for linkages of energy that lack either a form or a fixed location, and what is “energy” anyway?

Don’t forget: nobody inhabits the brain. No invisible being wafts through the nerve endings, peers through the eyes, listens from within the ears, and speaks through your mouth. The eyes are not windows. There are nerve impulses, but no one reads them, counts them, translates them, and ruminates about them. Hunt for as long as you want, there’s nobody home. The world is contained within you, and you’re not there. “You,” seen from inside, are cobbled together on a makeshift basis: a field of vision amounting to no more than a few millimeters, and already dissolving into nothing at the outer edges, containing blind spots, and filled with mere habit and a memory that retains very little, most of it invented. Consciousness is a mere flicker, a dream that nobody is dreaming.

F appears again and a human being is dismembered in the course of a few pages: gifted, gutless, vacillating, egocentric to the point of sheer meanness, self-loathing, already bored by love, incapable of engaging seriously with anything, using everything including art as a mere excuse for doing nothing, unwilling to take an interest in anyone else, incapable of taking responsibility, too cowardly, incapable of facing his own failures, a weak, dishonest, superfluous man, good for nothing except empty mind games, bogus art lacking all substance and the silent evasion of every unpleasant situation, a man who has finally reached the point of such aversion to his own self that he has to assert that there is no such thing as a self.

But even this third part is not as clear as it seems. Is this self-loathing really genuine? Given the representations above, there is no “I,” and this entire exploration of consciousness is meaningless. Which part supersedes which other part? The author gives no indication.

After Marie’s father, Eric, is financially destroyed he is forced to hide out in the presbytery of Martin’s church. He drops by Marie’s house twice a week to take her to the zoo or the cinema. During these visits he speaks with her about his financial situation and she doesn’t understand a word. By this time, Eric’s twin brother Ivan has disappeared. Marie tries to sort it all out.

“Nobody learns Chinese,” said Marie, because it was too hard, and there was no point, how could anyone find words in all those brushstrokes? And what if even the Chinese were only pretending they could? It was possible—she did the same, pretending she understood what her father was talking about when he kept explaining to her that the big crisis had saved him.

Marie knew the way you were supposed to look so that it seemed you were understanding everything. She used this look in school, and it was often enough to get her good marks. And she always put it on when her father decided to tell her things that were important. He believed that the two of them were alike and that she understood him better than anyone else did.

As she was watching her father go, she thought of Ivan again. It was only recently that she’d grasped that maybe the riddle would never be solved. Never, which meant: not now and not later and not even much, much later, not in her whole life and not even after that. She often found herself thinking how he’d once explained to her in the museum why artists painted ugly stuff like old fish, rotten apples, or boiled turkeys: it wasn’t because it was about the things themselves, it was about painting the things, so—here he had looked at her solemnly and spoken very quietly, as if he were betraying a secret—so what they were painting was painting itself. Then he’d asked her if she understood, in the same voice her father always used when he asked her the same question, and she’d nodded the same way she always nodded. Her uncle had always seemed a little weird to her, because he looked so exactly like her father and had the same voice and yet was someone else. Things were sometimes strange. People painted fish in order to paint painting, bicycles fell over when you set them on their two wheels but were perfectly stable on these same wheels when you rode off on them, there were people who looked exactly like other people, and sometimes someone disappeared from the world just like that, on a summer day.

Kehlman’s book is a quick read or a long read depending on what you make of it. There are plenty of laugh-out-loud scenes and plenty of puzzles that will cause you to wake up at night and think. You may even decide to read it more than once.