The dump was a few miles west of town, about a half hour drive in our old truck. On Sundays we usually drove there to throw away our trash. The sour smoke from the fires that burned there irritated my eyes and the rank smell of burning garbage made me sick to my stomach but I didn’t complain. My mother let me rummage through the acres of trash and sometimes I’d find something interesting or useful. My parents were divorced so it was always my mother that took me. Sometimes my brother and I would bring our .22 rifles to shoot gophers. We’d try to smoke them out by setting fires in some of their burrows but we were never very successful.

Later, when I was in the Boy Scouts, I went on a camp out west of the dump. We set up in a valley nestled in the foothills below the coastal mountain range. It was well known that Indians once lived there in caves. My family had some grinding stones in our back yard that my grandfather found out there. During our camp out we investigated some of the caves. We crawled into them and looked for arrowheads or any other interesting artifacts we could find but all we found in the caves were large colonies of bats and piles of bat guano.

Some of my buddies whose families were poor lived in an abandoned prisoner of war camp on the northwest side of town. German prisoners were held there in the mid-1940s around the time I was born. One of the old guard towers is still standing. My mother told me she used to go with her girlfriends to watch the prisoners play soccer. Most of the boys her age were off in the war and some of the girls flirted with the prisoners. A few prisoners managed to escape. Most were captured and returned but one was never found. Some people thought he was still around after all these years living in one of the Indian caves in the hills west of town. From our fictional heroes, the Hardy Boys, we got the idea to search for this mythical German prisoner but, as with the Indian artifacts, we had no luck. This amused our Scout master no end.

When I was old enough to drive, I took a friend of mine out near those caves to hunt for deer. We planned to camp for a couple of days and hike around. We agreed to jerk any deer we killed, sell the jerky in town, and split the profits. Jerky was a hot commodity among the locals and we thought we could make some good money during the summer.

My friend’s name was Tommy Hart. He lived with his mother, Marjorie. No one knew who or where his father was. The scandal of Marjorie’s unexpected pregnancy was a source of town gossip for years. Several of my friends avoided Tommy but I liked him. In a way we were best friends.

The first day Tommy and I hiked all over the trails through the foothills of the coast range and we didn’t see one damn deer until it was almost dusk. Just when we were about to call it quits Tommy spotted our first deer for the day.

“Shh,” said Tommy and he pointed to some distant oak trees on the other side of the stream we had followed.

I could barely make out the buck standing among the trees.

Tommy held up three fingers to signify the deer was a three point. Before either of us could get our guns up something spooked the deer and it bounded away. There was too much cover for either of us to get a shot off.

“Damn!” said Tommy.

“Wouldn’t ya know it,” I said. “It’s too dark to go after him. He’s probably long gone anyway. Let’s come back tomorrow. We can find a way across this stream and take a look around. There’s no one out here to stop us.”

We got back to camp just in time to make a fire before it was pitch black. I’d wisely brought some sandwiches for our dinner so we were spared the burden of cooking.

The next morning we were up early, excited and anxious to find that three point or one of his friends. We returned to the stream and walked through a forest thick with oak trees and underbrush. We caught glimpses of quail, doves, and even pheasants but no deer.

After about an hour we came to a small marshy opening in the trees. There was a rocky cliff on the west side and I saw something strange.

“What’s that dark spot at the bottom of the cliff?” I asked Tommy. “It doesn’t look right.”

“I don’t know,” said Tommy “but it’s not a hiding place for deer.”

The stream ran faster here. It was about twelve feet wide but not too deep. On the other side was a broad rocky riverbed, a little sandy beach thick with sedges, rushes and grasses that led right up to the strange dark area I saw at the base of the cliff.

“I know that but I’m gonna check it out anyway.” I said. I left my gun and backpack with Tommy and made my way to the beach on the far side of the stream. When I got to the dark spot on the cliff, I discovered it was an opening to a cave. It had been plugged up with debris over time.

“What is it,” yelled Tommy.

“A cave I think. The entrance is plugged. I’m going to clear it out a bit and see if I can find a way inside.”

“Why the hell you gonna do that!” asked Tommy.

“Well, there aren’t any deer around and this cave looks interesting,” I said just as I crawled inside. “Hey, bring your flashlight over here. It’s dark but I think this cave is full of stuff. It looks like someone’s been living here.”

“The Treasure of the Sierra Madre,” laughed Tommy.

“Very funny. I’m serious, Tommy. There’s a lot of junk in here. Hurry up with that light.”

Over the years there had been all kinds of rumors about the foothills west of Arbuckle. Stories about a wild man, an Indian, a hermit, a fugitive, a monster, even ghosts living in this remote area that was rarely visited. Tommy was making a joke but we both knew this could be an interesting find. We might even come across something that would make us the talk of the town.

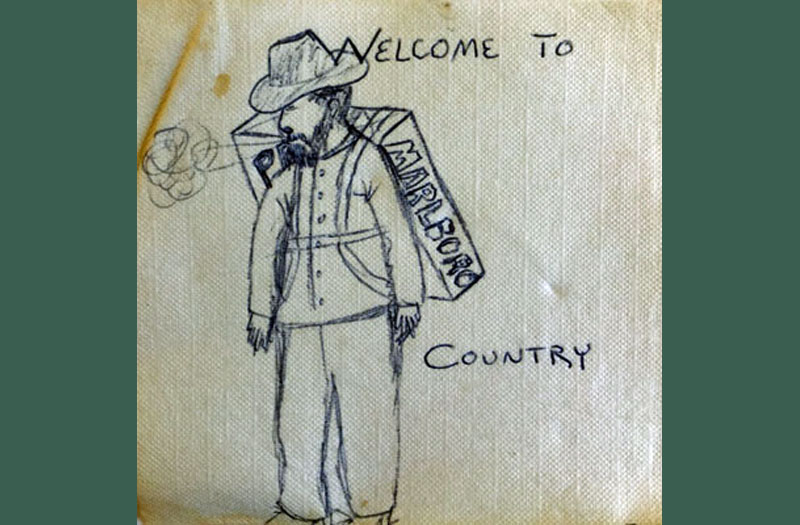

What we saw when Tommy brought his light took our breath away. There was a rusted axe, some fishing lures and hooks scattered around, an empty Old Gold cigarette pack, some empty rusted cans with the labels worn off, and a tattered shirt. The shirt was mostly rotted but clearly visible were the large block letters “PW.”

We both knew that the escaped German prisoner must have hid out in this cave. Just thinking about it gave me goosebumps.

“We’ve got to tell the cops about this, Tommy,” I said. “We’re gonna be famous. This is really something!”

“Hey! Look at this glass bottle,” said Tommy. “There’s a note inside.”

“Maybe we should just leave it alone,” I said. “ we don’t want to damage it. There might be some important information on it.”

“Too late,” said Tommy who had already pulled the note out. It was an old newspaper. We opened it carefully. It had June 11, 1946 written on it. Tommy’s face turned white.

“Isn’t that your birthday?” I said.

Tommy didn’t say a word. Next to the date were the names Marjorie and Thomas and under them Alfred Kelmer.

For several minutes neither of us said a word. We just sat there thinking. I knew this was Tommy’s call. He finally spoke and when he did I knew he was right and that I was going to do what he said.

“This is our secret,” said Tommy. “I’ll speak to mom when I sort this all out. You can’t tell anyone. Promise?”

I kept my promise. Until now. Tommy’s gone, rest his soul. I found out from Tommy after he spoke with his mother that his father, Alfred, managed to make it all the way to Wilbur Springs where he worked for a few years. Marjorie visited Alfred there with Tommy although Tommy was never told about his father. Alfred eventually managed to return to Germany. He stayed in touch with Marjorie and regularly sent her money to help with Tommy’s support. While Tommy found out the identity of his father that fateful day with me in the foothills outside our town, Alfred and Marjorie felt it best for them all to keep their secret. So did I. Now that they are all gone, I think it’s time that people know what I learned from all this. War is complicated. People are complicated. Life is complicated. Hate is easy. Love is hard. There are no answers, only questions. And sometimes it’s best not to ask.

Good one.