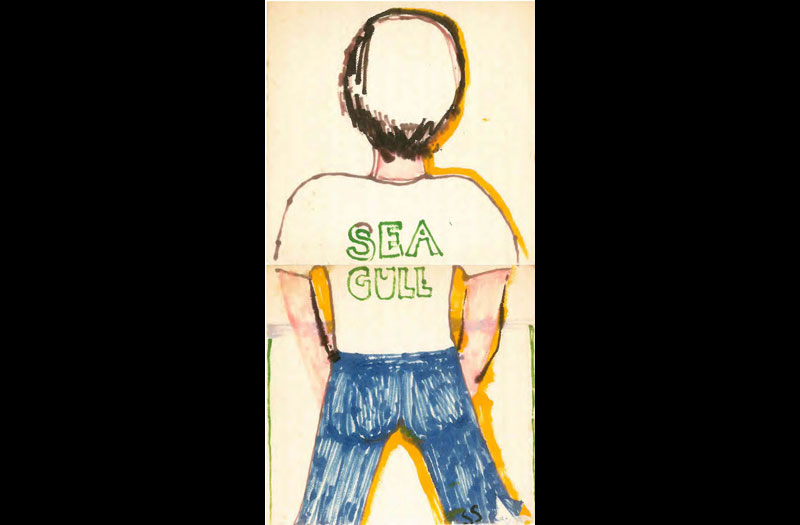

In June 2015 Jennifer Linley Taylor organized an auction and show of Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art at the Mendocino Art Center. You can read more and view other pictures and links HERE. You can find more on the Sea Gull Paintings HERE. And, visit the Food Page for more articles on the Sea Gull.

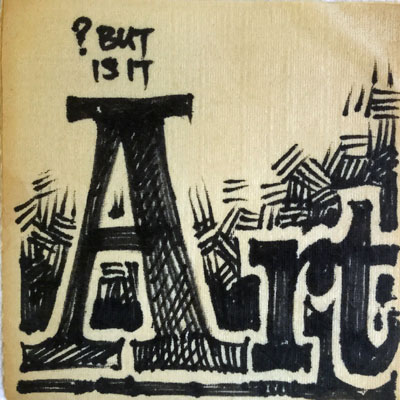

Napkin Art, Sea Gull Cellar Bar, unsigned

Mendocino Napkin Art: Friends Having Fun, Pros At Play

by Beth Robinson Bosk as published in A&E

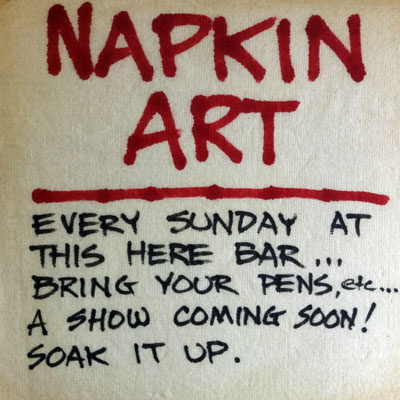

Around three o’clock any Sunday afternoon, the napkin artists of Mendocino begin to group at a long table lengthened by another or two upstairs by the window well at the back of the Sea Gull Cellar Bar.

The table has been compared to that famous solid old oak table at the Algonquin Hotel in New York, as Mendocino has been compared to Greenwich Village of the 1920s. But here and now the combustion of wry and fertile minds is more democratic, outreaching – the conversation unburdened by Freud.

Painters James Maxwell, Estelle Grunewald, Mark Eanes create ephemeral doodles; humorists Max Efroym, Jack Haye, Roy Hoggard spawn cartoons by the dozen. Sula Combs, a sculptor, daydreams pastel elephants on paper. Sandra Lindstrom quietly executes exquisite framed vignettes. For collagist Karen Kesler – with an art center to run – the napkin art is just about the only personal art she has time for now, a way to keep that pump within herself primed.

But in addition to this regular core, passerby wit is made welcome, the very odd are included, every shy untried hand encouraged to try.

Napkin Art, Sea Gull Cellar Bar, unsigned

At days end, when hunger hits, one artist or another will spread out and arrange the afternoon’s work on the floor. The funny, the offensive, the treasure, the trash, given equal acreage. It is ART in the OPEN…Mendocino’s least covert activity…

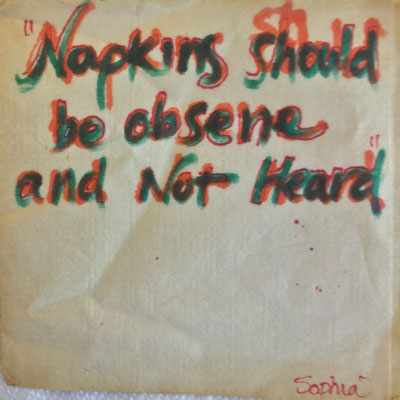

Napkin Art, Sea Gull Cellar Bar, Sophia

The collective memory forgets the first day the napkins moved from the bar to table. Remembers vividly the first napkin art “show.” Word comes that Jim Noyes, a local musician battling melanoma at a radical holistic cancer treatment center in Mexico, has run out of money there. A stack of napkin art is perched at the edge of the bar next to a bucket to raise funds for him. One dollar a piece, twelve dollars a dozen.

Then a popular Sea Gull barkeep, Becky Dodds (whose flaxen braids span the vertical in Jim Maxwell’s “Rumpelstiltskin” panel) suddenly needs open-heart surgery. The second napkin art show climbs up trellis frames between the murals behind the bar. Briskly the napkins are bought.

From this benefit comes the idea to show the art on gallery walls. The art is elaborated. Shrink-wrap is diapered over salvaged cardboard backs, cut into meticulous squares.

But the shows are only an offshoot. For the napkin artists, the importance is doing it.

James Maxwell sorts it out one afternoon. “Artists are involved on a graphic level. It’s an incredible vent for people who are visually oriented, like musicians who have to jam. Sometimes an art idea doodled on a napkin becomes final on a large canvas. But it is also a way to send a message through the normal daily din – like a tom-tom – put it down on a napkin and pass the napkin around.”

Max Efroym comes to the table each week after a long shift at a local restaurant. His opinion: the Shroud of Turin was the original napkin art. “This is brief art,” he muses. “Doesn’t take much time to do. It’s a change of pace from seriousness. Even our serious stuff is ultimately playful. It takes the capital A out of Artist. Makes it easy for people shy about drawing in front of others to do it in front of others.”

Pentels appear. Someone will arrive with the state-of-the-art in magic marker. For the most part the table clutters with this year’s accumulation of colored sketch pens augmented by scraps of paper and fabric for collage. Sometimes boxes of catalogues occur. Kinky materials – like dressmaker’s pins – reach the table, inspiring a series of bondage napkins. Once, Sula Combs arrives with a molded napkin mortar.

A theme prevails, occasionally spontaneously – lifted from the Sunday morning headline. More often, the theme is agreed upon during the week in casual contact – seasonal bunnies, dogs in and out of heat, sow bugs, udders, sperm – a myriad of other ideas.

And always, amidst the alcohol, popcorn and pens, the basic raw medium – virgin stacks of disposable tissue, standard size Zellerbach napkins furnished by the bar.

Australian termites have a relationship with napkin art. The termites finely chew their wood; they excrete tidy pellets, which become the building blocks of their complicated arched saloons. One termite ignores its pellets. Two show only a snuff of interest. Not until three, four – some critical number of termites – feel each other out do they simultaneously begin construction – incessantly building, making multitudinous choices, doing incredible work. Timid and morose solitary termites touch antennae; minds meld, a colony of imagination soars.

To doodle at a bar on a napkin invites comment and camaraderie. (Better than drinking alone, thinking with your fingers.) To move pen and napkins and people to a table creates a cradle for culture.

Sandra Lindstrom sums it: “Napkin art is catalytic action where two ideas make ten.”

In one hundred monkeys tradition, no doubt napkin art will suddenly leap to other places, other bars. When I last talk to James Maxwell he is reading destinies into the alphabetic rendition of names. On napkins of course. The table is surrounded by a new batch of folks with blank napkins in hand. There’s an aspect to Maxwell that flares from a quote by Blake: “He who would do good to others must do it in minute.”

To James Maxwell it’s very simple. “We are serious artists. This is our time to play.”

To visit the Kelly House Museum collection of Sea Gull Napkin Art, go HERE.

WHERE ARE YOU: MAX EFROYM????