[Click on BLUE links for sources and more information]

Think in the Morning publishes Guest Posts from time to time. Our friend Mitchell sent this recently which we offer as presented.

David, I thought this piece might interest your blog readers because so many Seagull alumni and friends were, and still are, interested and involved in theater. In 1985/86 Sharon and I made a trip to Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary when they were still Soviet Bloc countries, researching material about puppet theater for adult audiences. Our intent was not to study political or social consciousness theater, so much as to be an introduction to a neglected art form that theater people and others might appreciate and find useful today. It was written just before the internet was beginning to explode and social media and the information overload fuse had not yet ignited but was sputtering.

My interest in puppet and mask theater began more than forty years ago, after having written plays for children where inanimate objects were brought to life. I had also written several adult plays staged in small theaters, schools and libraries, all of which incorporated mask and puppet techniques.

Sharon was a professional photographer in 1985/86, interested in theatrical photography and portraiture. Before attending the professional photographic training program at City College in San Francisco, she had begun work on a doctorate in anthropology, and while working on anthropological research in Mexico fell in love with ethnographic puppetry and theatrical photography. Puppet theater is one of the most popular of the theater arts, especially in Europe, most especially in Eastern Europe. The most obvious reason is that puppet theater is a theater of symbols, as contrasted to live actor theater of character. There are no fixed rules stressing symbol over character or vice versa, or where the two meet. Philippe Genty, one of the world’s finest solo puppeteers, confronts this directy in his study of one puppet’s insistence to free himself from control:

Here are a few reflections of the adult puppet theater we saw on our travels that will serve to illustrate this difference in practice and how artists have attempted to bridge symbol and character. It could prove particularly useful for those interested in making social and political theater more relevant today. Puppet theater can bring interest to issues that are not easily discussed in live productions, is inexpensive to produce compared to live actor theater, can be scaled to audience size, involves sculptural design and construction, poetic expression, and musical creation.

Sharon Baronofsky Photographer

Sharon Baronofsky photographer

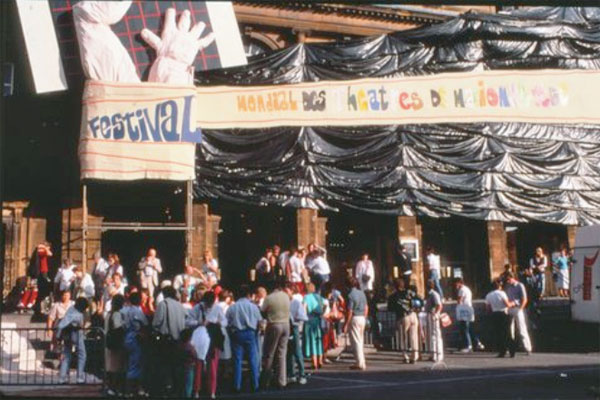

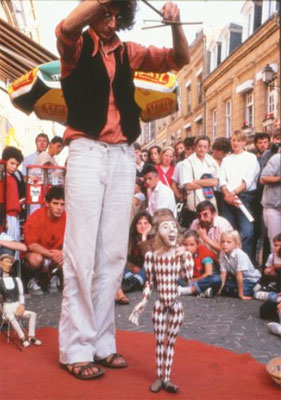

All the puppeteers we met in Europe were very interested in getting favorable reviews from American reporters–even freelancers like us with thin credentials; though by August 1985 we had published articles about puppet theater for adults in Paris, London, Connecticut, and also Charleville Mézières France, home of UNIMA (Union Internationale de la Marionette). We had attended the VII UNIMA World Festival in September 1985 where we interviewed puppet masters from around the world, and Sharon began developing a collection of hundreds of magnificent photos. Once puppeteers learned that our interest went beyond children’s theater they invited us into their homes and studios where they opened up to us and were most generous with their time.

We spent over a year in our study, saw more than a hundred shows, interviewed performers from around the world — and wrote a book of some 300 pages that did not interest publishers at the time. We finally ran out of time and money, then moved on to other unrelated activities in our lives, with no regrets whatsoever and several published illustrated articles. Here are a few scenes gleaned from the pages of our manuscript to illustrate how symbols are employed in puppet and mask theater. Details about our personal and social interactions with artists, which were quite wonderful and useful, filled my old journal pages. I would enjoy sharing them with anyone interested.

One of the most fascinating shows we saw, in May 1986, was a puppet production of Franz Kafka’s novel TheTrial in Bielsko-Biala Poland and in Pécs (pronounced PESH) Hungary, each, to our knowledge, unaware of the other production and each with its own unique script and staging based on the novel. Why such theater was permitted in Soviet bloc countries interested us, and we weren’t disappointed. The dissolution of Soviet control over east Europe was then some three years away. But the mood was changing.

The Trial, written by Kafka, during the winters of 1916 and 17, was prescient of the totalitarian regimes that would come to power in Europe during the following 20 years. His novel describes a chief bank clerk who, in the book’s first sentence, awakens on his thirtieth birthday and is immediately served with an arrest order for trial for no reason he could imagine, and spends the rest of his life defending himself against the unspecified but serious charges.

It is easy to understand why the book would be attractive to puppet players because it is itself a symbolic story of interest today, not just for its metaphoric value, but also for Kafka’s surreal imagery. The Polish company, Wroclawski Teatr Lalek performed The Trial during the twelfth annual international puppet festival held in Bielsko-Biala in May 1986. The theater is located only 18 miles from the Auschwitz concentration and extermination camp, where, according to Wikipedia, at least 1.2 million people were murdered by the Nazis during WW II (I’ve read German estimates of 4 million). In this retelling of The Trial, the puppet Joseph K., has reluctantly come to a lawyer trying to get legal representation about his coming trial where he must defend himself against the unspecified charges. The lawyer is very interested in K.’s case but not at all interested in the charges against him or in moving rapidly in these kinds of cases. In fact, he is ill in bed.

Sharon Baronofsky Photographer

Meanwhile, in another room his nurse, Leni, attracts K.’s attention and seduces him. In the seduction scene, puppet K., is relating to a live actress, full-sized, full-bodied, scantly clad, removing her stockings in front of him.

Sharon Baronofsky Photographer

The show did not dwell on or show the impossibility of their love making because there was no need–though her presence served to focus attention; nor did anyone in the audience react to the absurdity, since by then it was obvious that the actress and the rest of the live actor cast were symbols of authority, while the puppet K. and other puppets in the show represented ordinary people. The Polish revolution against Soviet domination happened in 1989.

Another version of The Trial took place in the dining room of a hosiery factory in Pécs, Hungary. The performance was for the workers and used small puppets performing in Hungarian which we could not follow, but resembled an amateurish poorly staged child’s puppet play. We did not have the opportunity to interview any of the company and no French or English translations were available to us. It was a somber production and a somber audience. The Hungarian revolt against Soviet Russian suzerainty had been brutally put down in 1956. Before that, they fought each other during World War II. It wasn’t until 1991 that Soviet forces withdrew from Hungary. This version would no doubt have been approved by censors.

Here is a French version of the scene of the lawyer in bed.

Sharon Baronofsky Photographer

Joseph K. is in front of a portrait of the chief magistrate, the lawyer is in bed. By Compagnie Hubert Jappelle, Paris 1986. Updated information in English about Hubert Jappelle can be found HERE (go to link).

An altogether different adult puppet show, in the Bielsko-Biala festival, was performed by a German couple from Braunschweig, Enno Podehl and his wife Anne, founders of Theatre im Wind. They wrote and staged the puppet play Hermann, about an elderly trash collector living in Nazi Germany who is very poor and has no knowledge of what is happening around him as he goes about collecting trash in order to survive. Hermann lives with and loves a poor gypsy puppet woman, Johanna.

Sharon Baronofsky Photographer,

Hermann Helping hand No salt

Sharon Baronofsky Photographer

Sharon Baronofsky Photographer

Sharon Baronofsky Photographer

One day, Nazi puppet soldiers burst into his hovel grab Johanna by the neck and drag her away as Hermann cowers under a table in a corner of the room. He is heart broken and tries to find his love, and sometime later, while at the train station searching, he witnesses what is taking place in Nazi Germany.

This was symbolized by boxes overflowing with old broken eyeglasses and dentures is dumped at the train platform where Hermann sits in a corner and watches as the the box is emptied on the platform and the soldier goose steps off. A kerchief belonging to Johanna is casually tossed on the platform.

Sharon Baronofsky Photographer

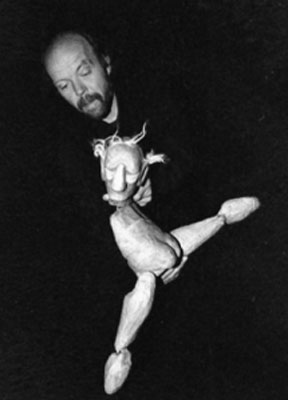

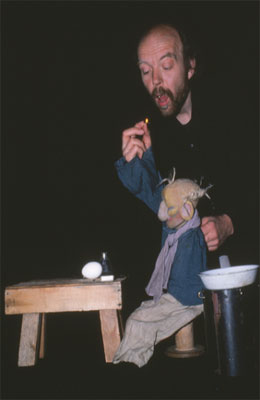

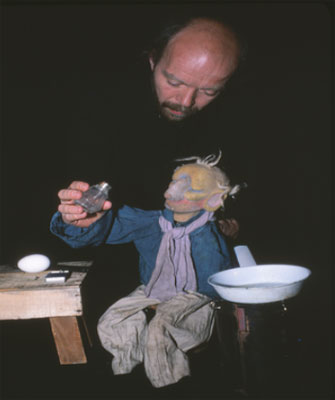

Hermann is not in the least heroic. He is a coward. The Podehls capture the raw emotions of the play using a puppet and theatrical techniques that acutely focus attention on the action. For example, Enno can be seen working very close to Hermann who is carved from blocks of wood and supported and manipulated by a rod fixed to the back of his neck, a form of puppetry called Bunraku, a Japanese adult puppet theater for more than 300 years. Anne and Enno work very attentively showing no expressions. Enno manipulates Herman’s rod and makes the fingers of his hand become Herman’s hands.

The audience readily accepts the size discrepancy. In another scene, Hermann lights a small gas hot plate with a real match. He then looks at the burning match, then at Enno, with a gesture suggesting ‘help me I’m just a block of wood,’ and Enno blows out the match, Hermann nods, then, having shared this instant of rapport, they are back into the play.

This intimacy of the character and the puppet breaks the dichotomy of symbol and reality and is more and more popular in adult puppet theater. It is one of the reasons many puppeteers enjoy working intimately in small theaters with small audiences, and one of the reasons puppet theater is the most consistently popular of the theater arts.

In an interview in The Drama Review in 1987, I asked Enno and Anne Podehl to talk about the affect of puppet theater compared to live actor theater:

ENNO: “Puppet theater is important because of its own unique expression, because it is intimate theater, because it is symbolic theater. . . . The main problem is that most puppeteers are not closely enough linked with the theater world; they don’t study theater, they are unaware, for example, of eastern theatrical forms of gesture.

This is the so-called puppetry ghetto, and for the most part it is caused by puppeteers themselves. Most adult puppet performers in Germany are variety acts or very light entertainment. We are considered outsiders in German puppetry—-but on the other hand nobody ignores our work.”

ANNE: “Enno sees more in terms of images, while I relate more to form. When we begin to work on a play, Enno has a picture in his mind and begins to draw. I go with the materials first. All the materials in the show are old, well-worn, well-used. . . “For the premiere we had built four ghostly puppets painted white, wearing white clothing with faint prison stripes. They were fastened on a stick, and I had a wagon and box. I opened the box, put them in, closed the box and took the whole thing away. We did this for three performances before deciding it was too weak, that we needed a stronger metaphor. In reality there were four million people killed in Auschwitz alone. They weren’t puppets; they weren’t ghosts.”

[The glasses and false teeth cannot help but remind people of the displays in the Auschwitz memorial down the road.]

One of the more recent works of Theatre im Wind/Theater Miamou is the 2012 production of DasBootshaus (The Boathouse). The trailer to this performance, with English subtitles, can be seen below.

It is the reflections of a man (played by Enno Podehl) who was a child during a war, any war, recalling an incident that comes to life around him when he was around ten or so, and living away from his family fleeing the war, living in the country, where the war impinges on his memory, his life, his loss, assisted by actors and puppets and objects. Mirjam Hesse’s performance as puppeteer, mime, and dancer masterfully shows how symbol and character can join.

In Chrudim Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic) we watched a performance of The Chant of Life performed by the Czech company Drak (Dragon), one of Europe’s larger puppet companies in 1986, with 39 members, including performers, constructors, technicians, artistic and performance directors. Having large lavish companies has been a familiar criticism of Eastern European puppet theater. Drak is the exception to this, under its director, in 1986, Joseph Krofta.

The Chant of Life is about the struggle between fascism and fundamental moral principles, with ordinary people played by puppets. In the most moving scene, beautifully crafted puppets of a man and woman are huddled together, arms clutching each other, standing in fear on the empty darkened stage, looking tiny under the glare of a tightly focused single spot light. The spotlight is held by a live actor concentration camp guard in a black uniform high on a wall searching for an escaped prisoner, with the spotlight aimed across the stage to an unseen figure, also high on the wall, angling a mirror and wiggling it so the light from the mirror reached the puppets as a sweeping prison search light. This was being staged three years before the Velvet revolution of 1989 resulted in the end of 41 years of one party communist government rule and the creation of the Czech Republic, whose first president was Vaclav Havel, a playwright known for his absurdist style.

Sharon Baronofsky Photographer

One of the most spirited shows in Chrudim was by the Italian group Teatro Gioco Vita from Piacenza Italy performing Homer’s The Odyssey, using shadow puppetry to create distortions and illusions by manipulating the shadow screen and projectors.

Sharon Baronofsky Photographer

Sharon Baronofsky Photographer

Teatro Gioco Vita is still (2019) very active and still utilizes shadow techniques but now mixes it all with full color shadow effects with live actors and dancers. From their start the company has been open about sharing how their effects are created and how they achieve effects that could only be imagined as coming from Hollywood special effects.

I’ll conclude this brief review with a description of one of the most moving puppet shows during our study. It took place during the Pécs festival – actually between shows while the curtains were closed and back stage was being prepared for a spectacular, and boring, black light children’s puppet show. There were hundreds of people in the audience, mostly children and mothers. Unfortunately we had no equipment to record any of it because the entire event was to be large Childrens puppet shows and we had seen more than enough of these. But what we saw between performances remains with me as a powerful impression and strong lesson about artistry and women performers. To fill the time between shows, two women – whom I later learned were telephone operators in Pécs – came in front of the curtain, one carrying a folding card table and cardboard box, the other carrying her cello and a chair. They were dressed in ordinary street clothes—perhaps they had just gotten off work. As the cello player began lovely Hungarian children melodies, the other woman produced a dummy head from the box that had no eyes ears nose or mouth, the kind of bare head used to display wigs. She reached into the box and produced a blond wig made of yarn in braids which she arranged on the head along with a flower, ribbon and bow, then added some rosy cheeks and smiling lips that made her look young healthy and innocent, and as she worked she began the story of a play called A Life. As the music changed the woman reached into the box and began to age the head with a laced shawl for its first holy communion, various child and teen hairdos, hats, and other things I can’t remember, while all the time narrating the story of her life, lovingly – or something like that. We had no idea what was being said, but the incredible music spoke volumes. Bela Bartok was Hungarian and collected the folk songs of Hungary while a young musician. This woman was playing them. The music, combined with the aging symbols, easily recognized by the audience and the narrator’s intonations, made it easy enough for us to broadly follow the tale of the woman. The story progressed through her childhood and ultimately to marriage in a beautifully embroidered lace head scarf and shawl. As the narrator talked, she produced her husband, another bare head, and gave him a slick back hairdo, a mustache and subtle symbols of a wastrel that I can no longer recall. And as the marriage progressed, with heavy drinking and fighting and hitting with the cello making the scene palpable, the woman transformed into disheveled gray hair and a bruised face covered in dirt and blood as the music responded.

At this point in A life, I looked over the rail of the balcony where we sat, and studied the audience of several hundred people below, mostly young children and women, and saw many women crying and brushing away tears. Sharon and I were crying. On and on the music and tale of the woman unfolded without us knowing a word, with the woman aging and leaving the man (thrown into the box), the woman knowing poverty, working hard until she died and was laid to rest in the box covered in a Hungarian shroud, accompanied by the haunting cello. Perhaps there was a particular story going on, or an all to familiar tale, but the details didn’t matter to us compared to the play going on with our imaginations – the faceless face of so many brutalized mistreated women. When it was over nobody applauded because the house lights immediately dimmed, the women left the stage, and the music began for the featured performance by a huge national puppet company performing a folk tale, with black light puppets flying, dancers doing fantastic acrobatics, spectacular rainbow lighting—and revoltingly bad imagery. I tried to meet with the women, but the festival’s scheduled activities precluded this.

There’s lots more to our study but that’s enough for now. Let me know if you would like more. In addition to the above puppeteers, we met with, interviewed and photographed:

Henk Boerwinkel – Figurentheater, Holland Philippe Genty – Company Philippe Genty, France Eric Bass – Sandglass Theatre, USA Peter Schumann – Bread and Puppet Theatre, USA East Indian Shadow Puppetree Yakshagana and Kathputli Marionettes, India Basil Jones – Handspring Puppet Company, South Africa … Plus many many others involved with construction, music, directing, etc.

The climax to our study of East European symbolic theater happened during our stay in Bilesko-Biala. We were told by the festival director that the puppet theater headquarters building was once a large splendid synagogue. In destroying the temple the Nazis discovered a tunnel leading across the main street to a rail siding (adjacent to the restaurant where we took most of our courtesy meals, overlooking the tracks). Through this tunnel, we learned they marched the Jewish population of the city, all 35,000, onto cattle cars for the brief journey across gentle farmland in the foothills of the Tatra Mountains, to the town of Ozwiecim (renamed Auschwitz by the Nazis) then a few kilometers beyond to the camp.

And then there was The Russian puppet who became President of the United States.

This is fascinating…

Thank you Mitchell, Sharon and David