The idea that there are truths we cannot know for sure is disturbing to those who want an answer for everything. Kurt Godel was a disrupter. He showed (proved) “that mathematics could not prove all of mathematics.” (see Waiting For Godel by Siobhan Roberts, The New Yorker, June 29, 2016). The effect Godel had on a philosopher like Moritz Schlick (or Bertrand Russell or a mathematician like David Hilbert) is portrayed in the following scene from a lovely book by Janna Levin: A Madman Dreams Of Turing Machines. Godel starts the scene by asking what seems at first like a simple question.

“How do you recognize a fact of the world?”

Moritz laughs, but not rudely, and nods, which loosens his hair only marginally from its proper place before he stops himself, slightly sorry for his reaction as he takes in Kurt’s serious expression. “It is a fair question,” he confesses. “How do I verify a fact of the world?” Such a simple question. He cannot even answer this simple question. Despite his proclamations, Moritz knows something is wrong. No matter how disciplined he is in his adherence to logic, he cannot make sense of a method to verify facts of the world. He comes to ever narrowing definitions that magically take him farther from clarity. Spirals of rational thinking thread him closer to understanding only to unravel disappointingly far afield. As Moritz reaches for his coffee his motion is very slow, and it seems so even to him, the perspective telescopic. His fingers surround the cup and feel the heat. He pulls the cup to his face and sees the dark liquid. “How do I know this cup exists? I don’t,” he admits to himself. “I don’t.”

Being honest he can be sure only he sees. He can be sure only he touches. He watches Olga pull on a mammoth cigar. She has a calm about her, always at ease. The smoke drifts in curly plumes sifting through her lashes. She doesn’t seem to mind and even tends to hold the burning cinder vertically and uncomfortably close to her eyes. Her hair is collected loosely at the nape of her neck, a rumpled frame for her big and broad broken eyes.

She cannot see the cigar. What does it mean for her to say there is a cigar between her fingers? The meaning of the statement is that she feels the tobacco-stuffed wrapping. She tastes the juice and smoke. She senses it. Does it exist? That is not a meaningful question.

But what really arrests Moritz, what keeps his fingers in a frozen clutch around the cup, coffee suspended near his chin, is this question: Does Olga exist? He hangs there for what seems like a very long while. The conversation stalls, suspended along with the coffee.

“Olga?”

“Yes, Moritz. I’m here.”

She reaches over and hooks his thumb with her forefinger. The rest of her fingers scramble over to clasp his hand. But all Moritz concedes is that he can feel what he has learned to describe as pressure on what he believes to be his hand.

What is real and what isn’t? I recently came across an interesting blog by Nancy Hillis at The Artist’s Journey called Creativity, Yogi Berra And The Nature Of Existence. Parts of the blog are summarized below in italics.

The Story Of Three Umpires

It is known as the story or joke about three umpires, and it describes a conversation between three referees and how they judge actions in the game of baseball.

The first umpire says: “There’s balls and there’s strikes, and I call ’em like they is.”

The second umpire says: “No, there’s balls and there’s strikes, and I call ’em like I see ’em.”

The third umpire says: “There’s balls and there’s strikes, but they ain’t nothin’ until I call ‘em.”

Each umpire embodies a particular view of reality. According to Hillis:

The first umpire ascribes to the philosophy that there is an external immutable reality that has no particular relationship to the person perceiving it. Moreover, they are convinced that they have perfect access to this reality and merely have to report back this objective truth to the observers of the game. [As an artist Hillis offers the example of Audubon’s paintings of birds that are intended to help naturalists identify them in the wild.]

The second umpire cracks the door open to a participatory reality … To reiterate, there is an objective reality but we only have access to bits and pieces of it. We have to use the power of contemplation to infer the existence of the higher truth from the flickering shadows that we are able to observe directly because of the limitations of our senses … The second umpire has only one point of view and is not omniscient, and therefore acknowledges and tries to account for that limitation and does not claim to report the Truth. [Hillis offers Claude Monet’s studies of Rouen Cathedral, over 30 paintings of the same object under different circumstances (different times of day, different weather conditions, etc.) as an example from the art world.]

But it’s the third umpire (says Hillis, that) we want to focus our attention on. By saying that actions aren’t anything until they’re “called”, s/he is getting at the nature of perception and consciousness. Giving something a name creates an identity that was not there before … [He] is not referencing an agreed upon external reality like the first umpire … and often not even referencing a personally perceived objective reality like the second umpire … but instead establishes that the process of perception and expression is a subject unto itself.

Hillis associates this third world view with abstract art. In literature I would call it fiction, something “created from the imagination, not presented as fact, though it may be based on a true story or situation” (Encyclopedia Brittanica).

In my narrow-minded way I’d say the three umpires fall into three distinct groups: True Believers, Scientists and Artists.

Like the first umpire, True Believers think there are absolute truths which they and only they have access to.

The mindset of the second umpire is aptly described by the Nobel scientist Richard Feynman: “A scientist is never certain. We all know that. We know that all our statements are approximate statements with different degrees of certainty; that when a statement is made, the question is not whether it is true or false but rather how likely it is to be true or false.”

The third umpire, the Artist operating in the realm of the imagination, attempts to transcend the truth and lead us to a different form of wisdom. Consider the following two examples.

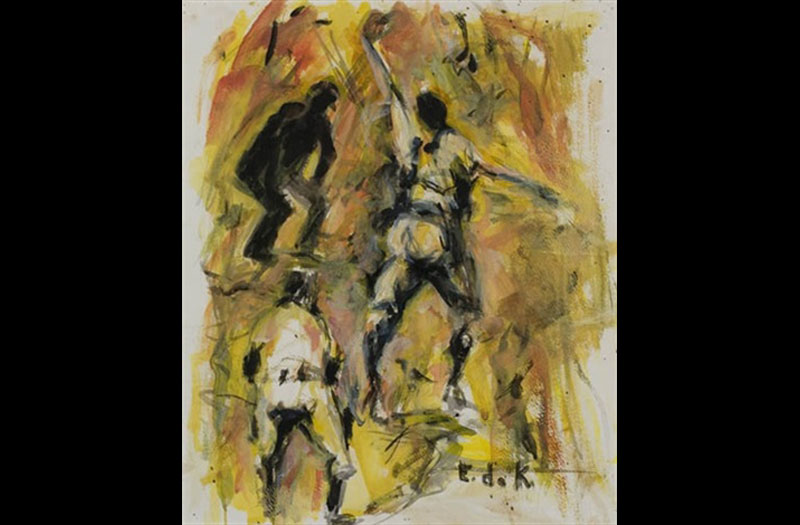

Abstract artist Elaine De Kooning was an avid baseball fan who was fascinated by their “stances,” and traveled with the New York Yankees and Baltimore Orioles in 1953 and 1954. Her painting (at the top of this page) “The Baseball Catch” is on display in the Frank and Peggy Steele Art Gallery at the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Author Stephen King said this about his novella Blockade Billy: “I love old-school baseball, and I also love the way people who’ve spent a lifetime in the game talk about the game. I tried to combine those things in a story of suspense. People have asked me for years when I was going to write a baseball story. Ask no more; this is it.”

In baseball there is an external immutable reality. It’s called the strike zone. (Not exactly immutable because it changes over time but at any point in time it is carefully defined.) Unfortunately, whichever system is used to call balls and strikes is flawed. Studies show they are wrong about 15% of the time. True Believers, of course, would argue until they’re blue in the face. Scientists would expect some of their decisions to be flawed. Artists would say with Keats “beauty is truth, truth beauty—that is all ye know on earth and all ye need to know.

Thankfully, in the most important games like the World Series, it is rare for a called third strike to end the game. It happened in the 2010 World Series when Sergio Romo struck out Miguel Cabrera on a called strike and the San Francisco Giants beat the Detroit Tigers. As far as I know, the umpire was accurate on that call.

Charles Peguy said: We must always tell what we see. Above all, and this is more difficult, we must always see what we see.

What we see depends on how we see. The poet William Blake cautioned us to see through, not with the eye.

“This life’s dim windows of the soul

Distorts the heavens from pole to pole

And leads you to believe a lie

When you see with, not through, the eye.

William Blake, The Everlasting Gospel