Chester was erudite and twisted; this is a lovely combination.

Peter Lit, The Caspar Inn

We are each a reflection of our culture. In the melting pot of America, a culture may be no more than a family tradition. It could be something you invent, as did the Beatniks and the Hippies of the “Sixties.” Or, it could develop over a lifetime. Appreciation of different cultures is the sign of an open mind, a good thing as long as your mind is not so open that your brains fall out as the physicist Richard Feynman used to say.

I first took over the Sea Gull Restaurant and Cellar Bar in Mendocino on January 1, 1973. I was a kid at the time. Now I’m an old man. Before closing the deal with my lifelong now sadly departed friends, Martin and Marlene Hall, I spent a couple of months working every job in the restaurant from dishwasher to front desk, from cook to bartender. I was excited but terrified. I had no experience running any business let alone a restaurant and bar with nearly fifty employees. I couldn’t cook or mix drinks. I had college degrees but they were in mathematics, statistics and economics. While I grew up in a small town, I had lived for nearly a decade in the Bay Area, Palo Alto and Berkeley. Now, here I was, back in rural America, about to take over a giant project for which I was, by any reasonable standard, unprepared. To put it in hackneyed terms, I was a fish out of water, wet behind the ears. Or maybe I was a ten foot blue lobster. Now, that would have been something.

Blue lobsters are rare. Estimates by the University of Maine Lobster Institute put the likelihood of catching a blue lobster as one in 200 million.

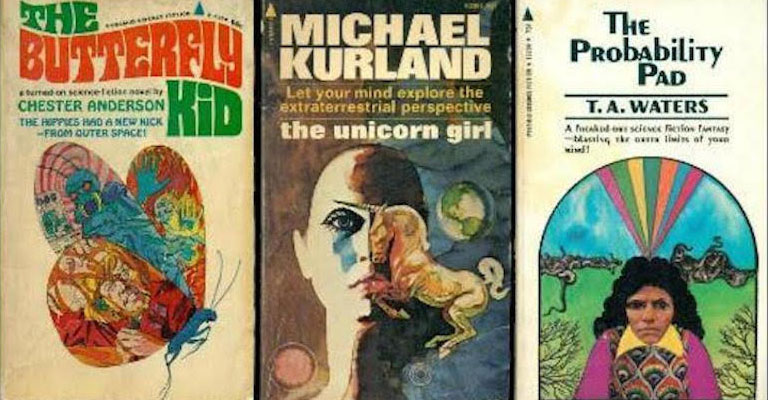

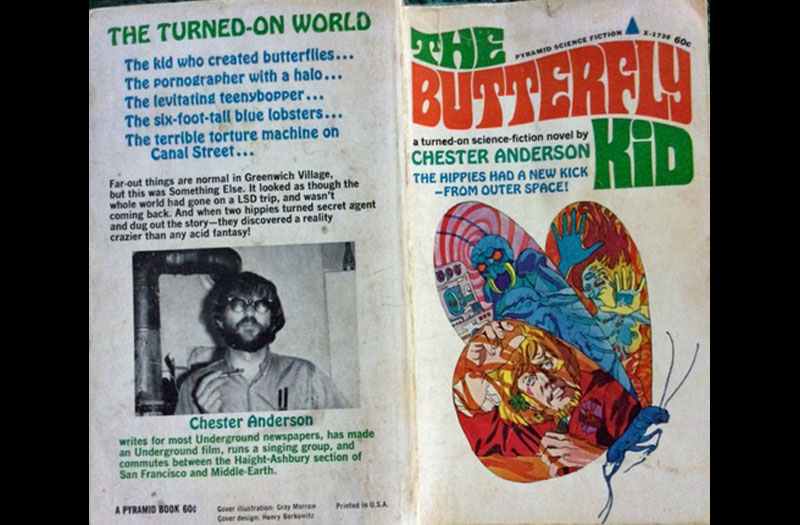

The sign of a good book is that it lasts. Chester Anderson’s The Butterfly Kid (1967) is the source of my reference to the ten foot blue lobster. Ten foot tall blue lobsters were the imaginary beasts, the evil (but nonviolent) characters in Anderson’s science fiction cult classic. The book has been re-released as an e-book on Amazon Kindle (50 years later) along with two other books that make up the Greenwich Village Trilogy (The Unicorn Girl by Michael Kurland and The Probability Pad by Tom Waters). FOREWORDS to all three books and a couple of reviews are pasted below. Together the books and the FOREWORDS provide a unique insight into that (use your own adjective) period we call the “Sixties.” It was from the “Sixties” that I walked into Mendocino and The Sea Gull. There, surrounded by multiple contradictions, I found my culture.

In our last blog, The Phoenix Myth, we mentioned another book that has held up well—The Search for Goodbye-To-Rains by my friend Paul McHugh. (Paul’s new book—Came A Horseman—is out December 20—available at Gallery Bookshop in Mendocino and all online sites, etc.) Paul told me that in The Search for Goodbye-To-Rains: I tried to capture some of the gestalt of the 60s/70s and think I succeeded to some degree. Both McHugh and Anderson did that. They captured the magical qualities of those years each in their own way. I asked Paul if he knew Chester. His response:

He [Chester] had a story he loved to tell (I think I heard it about three times). This was while he was living in NY, and was part of the coffee house/music/hipster scene there…. apparently to the point that Yoko Ono invited him to monthly soirees and impromptu improv music events at her spacious apartment. The deal was, after smoking some refreshments, Yoko would pass out these cards to people that had cryptic instructions on them about making various sounds – which she would then record, and edit, and add to her, ah, “unusual” musical concoctions. At one of these events, Chester finally got the card he’d been waiting for. It told him to, “Make a sudden, loud, strange noise.” He stood up, took a cherry bomb and matches out of his pocket. He walked past the coffee table, picking up a heavy glass ashtray as he passed. He went to Yoko’s open grand piano, placed the ashtray on the strings and put the cherry bomb in the ashtray. He glanced over his shoulder. “Yoko had this odd look on her face, but she didn’t stop me!” Chester said. He lit the fuse of the cherry bomb, and gently closed the lid of the piano. “I carried out her instructions to the ‘T,'” Chester said. “And it was really fun. But for some reason, I never was invited back.”

One of the perks of the restaurant business is that you get to see and sometimes meet an array of fascinating, often strange, sometimes eclectic, people doing ordinary human things like eating and drinking. This includes famous musicians, actors, authors, poets, and even a few wealthy movers and shakers. Of course, it’s the mostly silent, “ordinary Joes”, you know, the kind of folks that make the world go round, where life’s wisdom resides if there is any. The artist’s job is to bring that wisdom to us.

Chester Anderson’s The Butterfly Kid was published in 1967 and was nominated for a Hugo Award. Anderson moved around a lot. He was born in Stoneham, Massachusetts in 1932 and raised in Florida. He attended the University of Miami before becoming a beatnik coffee house poet in Greenwich Village and San Francisco’s North Beach. He spent time in and around Los Angeles. Later, he lived in a cabin on the Russian River. After that he lived for a number of years in Mendocino prior to his death in Homer, Georgia.

Sea Gull Bartender Bruce Clawson told me: I knew Chester well. I actually knew him before he came to Mendocino. He lived in Isla Vista when I met him and he was good friends with Alfonso Riede [owner of Alphonso’s]. I think that was because of their mutual love of classical music. I don’t have any stories about him, we ran into each other in Mendocino of course. I would make him the occasional martini when I worked at the bar.

Anderson was “a gifted musician, played two part inventions with two recorders simultaneously, played duets with Laurence M. Janifer at the Café Rienzi. He also directed and acted in theatre while in Mendocino.

When the “Sixties” started depends on where you were and what you were doing at the time. It lasted a bit longer in sleepy Mendocino. Richard Lupoff in his FOREWORD to The Unicorn Girl (see below) gives his opinion:

[The Sixties]: Some people argue that the era began with the election of John F. Kennedy to be President of the United States. That was November, 1960. Others argue that the Sixties really began with Kennedy’s inauguration in January, 1961, or with his assassination in November, 1963.

Maybe the Sixties originated in England with the rise of the Beatles, Twiggy, and the Carnaby Street fashion fad, and American politics had nothing to do with it. Or them. Maybe the phenomenon (or collection of phenomena) that we call the Sixties was imported to the US.

But I know exactly when the Sixties ended. They ended on that glorious day in August, 1974, when Richard E. Nixon resigned the Presidency of the United States. That one, I will assert with absolute conviction. I was sitting in my friend Jerry Peters’ living room when Nixon came on TV and read his statement. Jerry and I toasted the event and then went for a walk around the neighborhood and you could tell that an era had ended. [Richard A. Lupoff, FOREWORD to The Unicorn Girl-see below]

My first experience with the Sea Gull literati (no one ever called them that) was meeting Robin White. He was the author of several novels and one notable nonfiction. He won the Harper Prize in 1959 for his novel Elephant Hill and an O. Henry Prize in 1960 for his short story Shower of Ashes. He was not a man of the “Sixties”but he did display some of the qualities.

While attending Stanford he [White] was a prominent member of a bohemian colony in Palo Alto on Perry Lane, which writer Tom Wolfe described in “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test” as a place where people never shut their doors “except when they were pissed off.” White shepherded novelist Ken Kesey into the community, but, according to Wolfe, regretted doing so because of drug use by Kesey and his traveling band of “merry pranksters.” White later moved to Mendocino, where in November 1974 he led 500 local artists and other bohemians in a somewhat whimsical effort to make Northern California a separate state. Its failure did not seem to faze him. “Well,” he told The Times in 1976, between sips of beer, “if at first you don’t secede….” [L.A. Times obituary]

Bartender Dick Barham told me he made beer and martinis for Robin White in the old (downstairs) Sea Gull Cellar bar. I doubt White crossed paths with Chester Anderson. If he did, given White’s opinion of Kesey, I suspect neither would have found the encounter enjoyable in spite of Chester’s unique talents as a writer, artist, and musician.

Peggy and Jaime Griffith who ran 955 Ukiah Street Restaurant in Mendocino for thirty years shared this anecdote about Chester:

A vivid memory—when we lived on Main Street, Chester was a main fixture hanging around Alphonso’s door—not going inside so he could visit with the neighbors passing by Alphonsos. It was a gathering spot for tobacco users. Chester was a friend of John’s (Jaime’s brother and former Sea Gull bartender) and our acquaintance. One time he was walking down Main Street almost dragging a large bag that was somewhat inconspicuous as to what he was carrying—a large amount of pot bagged by the pound that he was looking to sell or trade for food or mercantile. One of the many characters of Main Street. We lived with Bertram (artist Jim Bertram) on Main in between houses. Moved (artist) Dorr Bothwell 3 or 4 times borrowing Jim Meyers pickup, always was during the Spring winds fighting to hold down stacks of large sheets of art paper. Main Street was rich with many characters all mingling together—Johnny Granscog, Hilda Pertha, Bill and Jenny Zacha, Raymond Hee—it was a great period of time.

Before Mendocino, Chester lived in San Francisco’s North Beach. His experiences there are documented in many publications, for example in a biography of Richard Brautigan (Jubilee Hitchhiker: The Life and Times of Richard Brautigan by William Hjortsberg). Think in the Morning wrote about Brautigan’s stay at the Sea Gull in How Richard Brautigan Saved My Life).

Joan Didion’s essay (later book) Slouching Toward Bethlehem documents some of the Haight Ashbury of the “Sixties.” She tried to meet Chester Anderson to get his views on what was happening there but she failed to get a face to face. Today many writings of both are housed near each other in Berkeley according to Collections As Connectors—Holdings From Off Center. “The Summer of Love, from the Collections of The Bancroft Library” fortuitously brings together two representative figures who, in 1967, circled each other warily, but never met.

From Joan Didion, Slouching Toward Bethlehem:

Chester Anderson is a legacy of the Beat Generation, a man in his middle thirties whose peculiar hold on the District derives from his possession of a mimeograph machine, on which he prints communiqués signed “the communication company.” It is another tenet of the official District mythology that the communication company will print anything anybody has to say, but in fact Chester Anderson prints only what he writes himself, agrees with, or considers harmless or dead matter. His statements, which are left in piles and pasted on windows around Haight Street, are regarded with some apprehension in the District and with considerable interest by outsiders, who study them, like China watchers, for subtle shifts in obscure ideologies. An Anderson communiqué might be doing something as specific as fingering someone who is said to have set up a marijuana bust, or it might be working in a more general vein:

Quoting Anderson:

Paranoia strikes deep— Into your life it will creep— (Buffalo Springfield)

Pretty little 16-year-old middle-class chick comes to the Haight to see what it’s all about & gets picked up by a 17-year-old street dealer who spends all day shooting her full of speed again & again, then feeds her 3,000 mikes & raffles off her temporarily unemployed body for the biggest Haight Street gangbang since the night before last. The politics and ethics of ecstasy. Rape is as common as bullshit on Haight Street. Kids are starving on the Street. Minds and bodies are being maimed as we watch, a scale model of Vietnam.

Anderson described his time in San Francisco in a letter he wrote to a friend.

406 Duboce Avenue/San Francisco, Calif./February 9, 1967

Dear Thurl,

I did move to San Francisco, 1/7/67. Moved in at this address with Claude & Helene Hayward.

In San Francisco what’s happening is a drug-oriented social revolution centered in a neighborhood called Haight/Ashbury (those being the main intersecting streets thereof). A psychedelic community has sprung into existence, based essentially on pot & LSD. (Note: the pill inclosed with this letter is 1000 micrograms of LSD — hereinafter & henceforth called Acid. Divide it in half & share it with thine frau.) The operating principles of this community — more than 20,000 people — are Love & Freedom.

And it’s a lovely place. Everyone wears long hair and odd clothes & strange jewelry. I myself have grown a beard, given up cutting my hair, returned to boots, taken to wearing things & beads around my neck, & look generally quite picturesque, but fairly drab within my environment.

Naturally, I leapt into this community with the joy of an otter in water. With the 2nd BUTTERFLY check I made downpayment on a Gestetner silk-screen stencil duplicator & Gestefax electronic stencil cutter, with which Claude & I have set ourselves up as The Communication Company. The piece of paper headed thus explains what we’re doing.

Most of my writing lately has been for the company, and is enclosed. I’m also at work on a novel: THE LOVE FREAK, set in & playing with this community. This is the one I expect to be a best seller.

Anyhow, I’m now a community leader and, since it’s a revolutionary community, a political/revolutionary/ultraradical leader as well. It’s all enormous fun, & I wish you would come out here & join me. You’d have no trouble supporting wife & Kind here. In fact, within six weeks the company will probably be able to afford to hire you. We’re beginning to make money.

Claude is advertising manager for the _Sunday Ramparts_ — the newspaper published by _Ramparts_ magazine. He & I have interested the magazine in the hip community (whose members, including us, are called hippies). So the magazine is using me, at $2.00 an hour, as a researcher, investigating the community & pulling stories out of it. What this means is that I’m being paid to do what I’d be doing anyhow, a very dolce arrangement.

Why have you not written? Did you get THE BUTTERFLY KID? Shortly I’ll send you a copy of FOX & HARE similarly duplicated. But why have you not written?

The Communication Company (a member of the Underground Press Syndicate) is about to publish:

High Tea (with notes)

A Handbook for Unicorns

Poems Good & Bad (i.e., every poem of mine I can still stand)

The Changes, a magazine of basically literary pretensions

The Underhound, a satire mag I used to run in my North Beach days

all of which, along with everything else we put out that’s appropriate, you’ll get for enjoyment & archives.

I am exceedingly happy. Money is no longer a problem. I’m high most of the time & about to get high the rest of the time. I’m busy, creative, engaged, involved, having a ball. Why haven’t you written?

I’m also writing a regular column on Total Art for the San Francisco ORACLE, a subscription to which I have entered in your name.

All the stuff in this mailing I wrote.

Love & joy,

[Signed Chester]

The Digger Archives, Chester Anderson Papers (CA 1963-1980)

Mitchell Zucker, a writer who has several Guest Posts on Think in the Morning, worked as a janitor for many years at the Sea Gull. Mitch told me he did not know or remember Chester Anderson but he did have a story about the Diggers with whom Anderson cooperated.

Aha, you mentioned the Diggers. During the 60s I was working for the university at Davis, building their psychology and ecology depts experiments, one of which involved studying I believe it was quails. I had the opportunity of obtaining dozens and dozens of eggs, which, as I recall were considered aphrodisiacs. Since I was friends with the diggers and spent time in the city with them, I supplied quantities of aphrodisiacs, much to their delight. Perhaps it was during this time that his [Anderson’s]name reached me. Maybe it was around 1964. But that’s as far as my 85-year-old brain can harvest.

The Butterfly Kid is a good book and of particular interest to me because of Anderson’s connection to Mendocino. On re-reading the book, I made a few notes. Anderson calls the jukebox in the Garden of Eden Coffeehouse the “Kallikak box.” I wondered what this meant, if anything, so I looked it up and discovered The Kallikak Family: A Study in the Heredity of Feeble-Mindedness and also Beatrice Joy Chute’s short story The Jukebox and the Kallikaks. I think it’ may be a whimsical muse on how listening to a jukebox can make us “feeble-minded”—something today’s technology-crazed crowd can appreciate. The “Reality Pills: whatever you imagine will be real no matter how kooky it seems, (LSD?) place the book solidly in what Jesse Jarnow calls the “psychedelic future.” The old Anderson proverb: anything is better than embarrassments is something our current President (Trump) agrees with. My particular favorite is: “Sturgeon’s Law” [which I’ve used often pontificating to friends and relatives]: 90% of everything is crap. Finally, Chester’s method of coping remains relevant today: “I allowed myself to hope. Hope is good for you.”

Chester was a gay man. He wrote about that life-style in two books: Fox and Here on which he teamed up with Mendocino artist Charles Marchant Stevenson and Puppies, a book he published under the pseudo name John Valentine. According to Peter Berg of The Diggers:

Chester Anderson was a Beat consciousness type who was in total rebellion against his Navy/military family. I believe his father was high-ranking, maybe an admiral. He had dropped out, and he was older than many of the other people who were involved with the scene. I would imagine the age range of the Haight-Ashbury was about 20 to 30. I was a little older, he was at least ten years older than I was. And he was a Sexual Freedom person. He had his own sexual preference issue. And he had acquired a Gestetner machine; Gestetner was an early Xerox-type printing machine, very well made by the way, that used color. At that time, Xerox was not in color, but Gestetner was. [smiles] I think he had obtained it under a false pretext. Anyway, he and someone who worked at Ramparts magazine, Claude Hayward, began something they called the Communications Company. They were struck by the Digger ethos, and they were going to be the ‘free’ printers. The form that they used was to produce daily or occasional 8.5 by 11 or 8.5 by 14 sheets of paper with various messages on them, some of them very helpful to people, like numbers to call if you had an overdose, or numbers to call for social assistance. But a lot of them were ones composed for example, for street events, or composed for expression, or had poems. When Martin Luther King was killed, David Simpson made one that had a splash of red, as blood, and the words, “Goodbye, brother Martin. Today is the first day in the rest of your life.” And we passed that out in the street. A lot of Brautigan’s poems first appeared that way. A poem that was rejected by the Oracle newspaper for its overt political content, written by Gary Snyder, was titled “A Curse on the Men in Washington, a curse against the Vietnam War.” A curse on the men and their children, by the way—that’s why the Oracle thought it was too far out. Anyway, we first published it as a street sheet—I know, because I got that one published. I imagine they did several hundred.

Two reviews of Anderson’s book worth reading are Panicky Teenyboppers and Casually Absurd and Hilarious, Chester Anderson’s The Butterfly Kid.

I could go on and on but this is already too much. FOREWORDS to all three books are below. Thanks for indulging.

FOREWORD

to Chester Anderson’s The Butterfly Kid

–Peter S. Beagle

El Cerrito, California

October 2019

Robin Williams is supposed to be the guy who first said, “if you can remember the sixties, you weren’t there.” It’s a perfectly good line, and as accurate as most such good lines. I’ve heard it attributed to a number of people; any number of aging stoners of my acquaintance still claim it as original, even when they have some difficulty remembering their street addresses. Personally, I usually go with a considerably older Italian saying: “Si non e vero, e ben trovato.” (If it isn’t true, it ought to be.)

Me, I have real trouble with the sixties myself. And I was there.

I already was living and raising a family in the hills of Santa Cruz, California, by 1967, when Chester Anderson published The Butterfly Kid. As Donald Trump is forever declaring, “Most people don’t know” that it is the first installment—for lack of a more exact term—of a legendary epic called in toto The Greenwich Village Trilogy, written in three sections by three different writers: Anderson; my truly ancient friend Michael Kurland completed the second part, The Unicorn Girl, the following year; and T. A. Waters finished off the whole unique opus with The Probability Padin 1969. The Butterfly Kiditself was nominated in 1968 for a Hugo Award. Unfortunately, that was the year Roger Zelazny came out with Lord of Light. Timing is everything.

I knew Greenwich Village well in those more-or-less innocent pre-acid days. To quote the great jazz poet Dave Frishberg, “I was hip when it was hip to be hep.” (In my memory, by the way, to call someone a “hippy” then meant that he or she was faking the style without ever getting it quite right.) One of my several painter uncles had a studio deep in the Village, and my buddy Phil Sigunick and I used to pose for him on a regular basis. He paid us five dollars each, and back then you could get some serious mileage out of ten dollars in Greenwich Village on a sunny afternoon. Our Bronx was as boring as home always is. But, oh, there were golden people hanging around MacDougal Street in our time, Sonny—as, of course, there were in Edna St Vincent Millay’s time and Charlie Parker’s time and Delmore Schwartz’s time. I know that I saw Lenny Bruce then (still in the process of becoming Lenny Bruce), and Woody Allen doing stand-up a couple of times, and any number of folk and blues singers you might want to mention. Dave van Ronk, naturally, and Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry; Larry Adler, the great harmonica player, and the tap dancer Paul Draper (both of them run out of the country in the fifties for singing the wrong petition or hanging with the wrong friends). Phil and I were more than once struck silent to spy our hero Josh White walking the street like a natural man. (What? Actually talkto him?) Hedy West … Judy Collins … Ramblin’ Jack Elliot … that grubby little kid everyone who caught him at Gerde’s Folk City called “Lockjaw Dylan.” It was that time, and we were that young. Everybody was young.

As are Chester (author and charming, candid narrator of The Butterfly Kid) and Mike (doughty, if chronically drowsy, sidekick). The time is some way beyond the sixties—though clearly not thatfar removed—and there’s this amiable, innocent kid named Sean. He’s just arrived from Fort Worth, Texas, and he’s a lead guitarist, and he makes butterflies. They’re increasingly big, increasingly numerous, increasingly beautiful butterflies out of nowhere—and he has absolutely no idea how he creates them. Nor do Chester and Mike. Nor does Sativa, Sean’s instant groupie. Nor, really, does anyone else in a Village turned even zanier than usual, more than usually populated by what had just better be walking fever dreams and more or less sweet hallucinations. It’s all very much as though all of New York City, south of the mystic region where Hew-ston Street becomes How-ston, has gone on the collective Trip of Trips.

The villain of the piece—and a truly grubby, slovenly, treacherous, pathetic piece he definitely is—turns out to be one Laszlo Scott, currently the purveyor of something he calls Reality Pills, which he scatters freely throughout the Village as the representative of an invasion of six-foot–tall blue lobsters. They’re quite courteous, immensely intelligent, and utterly nonviolent—though they have absolutely no objection to violence employed by another species, when it serves their purpose. Their purpose—with the willing assistance of pitiful Laszlo Scott (everyone in the Village, except for friendly blue extraterrestrials, despises Laszlo, and he knows it)—is to test out the reality-distorting Reality Pills on an audience of distortion-tolerant stoners, all as eager for the treat as Mr. Carroll’s oysters. If the results are as satisfying as the blue lobsters plainly expect them to be, the next step will be to introduce billions of gallons of “reality” into the New York City water supply, which will inevitably lead to utterly peaceful, utterly remorseless conquest of the entire planet, which, with any luck at all, might not even be noticed.

And the heroes of this epic? The true cavalry riding to the rescue in the nick of time, bugles ablare and banners a-snap in the wild wind of triumph?

Well … there are fourteen of them, counting Chester and Mike, racketing up to the New Croton Reservoir—and directly into it, courtesy of the legendary bus Furthur). They are more or less called he MacDougal Street Commandos. Many are muscians of one discipline or another—if disciplineis quite the word I want—often playing at their beloved Garden of Eden coffeeshop, under Chester’s direction(which may not be the right word either). And as a group they are generally too stoned to be juch afraid (thank goodness!). they say “groovy” a lot.

Okay. This is a silly story. It starts out silly, with all those butterflies and all those “groovies,” and it unquestionably gets sillier and sillier, what with the blue lobsters ruthlessly torturing the captive Chester by forcing his helpless mind to visualize the complete adventures of Donald Duck: “… 3V, wide screen, with full sensory participation. Fine. I’ve always enjoyed the classics.” But the lobsters are only warming up, and it gets worse.

Mind you, it’s not a perfect story (Nobody in the entire development of human speech has ever sounded remotely like poor Laszlo Scott, to start with.) The entire geological epoch has, of course, dated notably itself over half a century. I can testify (being quire nearl as old as Michael Kurland) that “hippy” flourished best and longest in the year-round Greek-myth climate of Northern California and withered early on in the cold, dirty sidewalks of New York City. Then, too, it’s impossible for me not to notice the lack of African American persons in the entire novel, since both Phil and I knew so many in the Village, even in those dear, dim days. As I’ve said, “Timing is everything.”

Given these caveats, what we do have is a very nearly pure delight. Each of the successor books takes off in a slightly different direction, but the three stories fit together like pieces in a cosmic jigsaw puzzle and re-create a time that perhaps never was. And without benefit of Reality Pills.

FOREWORD

to The Unicorn Girl by Michael Kurland

–Richard A. Lupoff

2002

FOUR WORDS:

Read. Enjoy. Trust me.

There, I always wanted to do that. Thank you for giving me the chance.

Michael Kurland’s The Unicorn Girlis a novel about a magical world, half-mythical, half-historic, half-imaginary. Of course it is. That’s why it’s magical. It is a lost world, too, a lost world called The Sixties.

What were the Sixties, and when were they? First of all, theydidn’t start at 12:00:01 on January 1, 1960, nor did they end at 12:00:00 midnight on December 31, 1969. There’s a good deal of debate as to exactly when the Sixties—that astonishing era that we call, as a matter of convenience, the Sixties—really began.

Some people argue that the era began with the election of John F. Kennedy to be President of the United States. That was November, 1960. Others argue that the Sixties really began with Kennedy’s inauguration in January, 1961, or with his assassination in November, 1963.

Maybe the Sixties originated in England with the rise of the Beatles, Twiggy, and the Carnaby Street fashion fad, and American politics had nothing to do with it. Or them. Maybe the phenomenon (or collection of phenomena) that we call the Sixties was imported to the US.

But I know exactly when the Sixties ended. They ended on that glorious day in August, 1974, when Richard E. Nixon resigned the Presidency of the United States. That one, I will assert with absolute conviction. I was sitting in my friend Jerry Peters’ living room when Nixon came on TV and read his statement. Jerry and I toasted the event and then went for a walk around the neighborhood and you could tell that an era had ended.

For better or for worse, the world was made new.

The Sixties were, to borrow a phrase from Chuckie Dickens, the niftiest of times and the nastiest of times. In some ways they were a flashback to the 1920’s, “The Era Of Wonderful Nonsense.”

In the Twenties, sheiks wore raccoon coats and straw skimmers and slicked-down hair; shebas wore short dresses and feather boas, rolled-down stockings and cloche hats. They all drank bathtub gin or bootleg hooch whether they liked it or not. This was called “striking a blow for freedom,” and when I was in the army thirty years later some of our old-timers still used that expression every time they enjoyed a libation.

In the Sixties, men paraded around in long hair, moustaches and beards. Love beads and bell-bottom trousers. Girls (!) wore granny glasses and granny dresses and long straight shiny hair and no makeup at all, or else they opted for miniskirets and oversized sun-glasses anchored tro trhe tops of rheir heads and dark eye-shadow and pale lipstick.

For somje of us the most important questions in the world were when the Beatles were going to release their next album, or whether trhe Jefferson Airplane’s music was as trippy as the Grateful Dead’s. (It wasn’t.)

And the drugs—can they nab me for a series of felonies I committed thirty years ago solely on the basis of this essay? If so, get a comfy cell warmed up ‘cause here comes Arch-Criminal Number One! I remember an icy winter’s evening when my wife and I were meeting our friend Steve Stiles to celebrate his birthday. We’d bought him a baggie of something wonderful but illegal and wrapped it in bright paper and tied it with a ribbon.

We’d arranged to meet in the East Village, and when Pat and I arrived there was Steve, just across St. Mark’s Place, and there was a uniformed police officer in the middle of the street directing traffic. We certainly wouldn’t jaywalk, so I hollered Steve’s name, drew back my arm, and flung the gift-wrapped package skyward. Itr arched high over the policeman’s head through a light fall of lovely, feathery snowflakes, curved gracefully downward, and landed safely in Steve’s eagerly outstretched hands.

The light changed, Steve strolled across the street, passing inches from the cop, and everybody had a good laugh, never worrying about how close we’d come to three pairs of handcuffs and a ride in the paddy wagon. Instead, it was off to the Fillmore East to hear the Mothers of Invention and Sly and the Family Stone.

Like our parents and grandparents in the 1920s, we too felt that we were “striking a blow for freedom.”

Those days were long ago, and the playful lifestyle of the era seems as remote and as alien to today’s world as the civilization of the druids who built Stonehenge or that of the Aztecs who constructed those mysterious pyramids in Yucatan.

But if all that playfulness was the light-hearted side of the Sixties, there was a serious side as well. There was the Civil Rights movement with its heroes like Martin Luther King, and Rosa Parks, its villains like Bull Conner and George Wallace, and its martyrs like Chaney, Schwerner, and Goodman. There were good guys like Senators Eugene McCarthy, and bad ones like John Mitchell and Richard Daley. There was the tragedy of Kent State and the horrifying police riot in Chicago, and behind so much of this, the Vietnam War, and behind that, the Cold War.

Remember the Black Panther Party and the Youth International Party? Remember, “Girls say Yes to boys who say No?” Remember movies like Easy Riderand Zabriskie Point? If you don’t, ask somebody who was there.

We treasured the books that this new consciousness and this new spirit of questioning spawned. Ken Kesey and Hunter Thompson and Tom Robbins hit the bigtime bestseller lists, and in the smaller world of science fiction there were topical novels by Michael Moorcock, Chester Anderson, Michael Kurland, Thomas Waters, Grania Davis, Norman Spinrad, and Robert Silverberg. I even wrote one myself, called Sacred Locomotive Files. The late Don Bensen bought it for one publisher and loved book so much that he went to bat for it in-house. He fought so hard to get it decent treatment that he got himself fired and had to buy it all over again for another publisher, once he’d got another job.

I think of all the people I knew and loved and admired in the Sixties, and what became of them. The era acted like a crucible. Some of my friends and heroes were destroyed; they literally lost their lives in the flames that were those years. Others were warped, distorted, dreadfully damaged, although they managed to survive and to some degree recover. But the majority of the people I knew in that era were tempered by the heat. Like iron, they emerged as better and stronger men and women than they had been before those strange and wonderful and terrible days.

And then, quite suddenly, the Sixties were over. Along came the Disco Seventies and the Go Go Eighties and the Dot.Com Nineties, and now we are living in a new millennium unlike anything that any of us could have anticipated.

Will there ever be another era like the Sixties? Oh yes, I think it’s inevitable. When the proper concatenation of economic conditions, social and political circumstances, and technological advances occurs—as old H. P. Lovecraft would say, “When the stars are right”—well, we had the Roaring Twenties and the Swinging Sixties and eventually we’ll have something else, something new and yet old, some fresh Era of Wonderful nonsense all over again.

When?

Ah, there’s the rub.

But, listen, I’ve been getting too serious and profound for my own good or for your amusement. Michael Kurland calls The Unicorn Girlan entertainment and also a fantasy, and he’s right on both counts. We all need an entertaining fantasy now and then, and Michael has created a wonderful one for us.

Just the other day I reread The Unicorn Girlfor the first time in more than thirty years. Seamlessly I found myself slipping from the grim present into a past that never quite existed, but nearly did, and surely should have. I found myself an invisible d’Artagon heading off on an adventure with the three mod musketeers Anderson, Kurland, and Waters, and their lovely companions Sylvia and Dorothy. My only complaint with the adventure was that it ended too soon, but that’s always a sign of a book that one loves.

Michael tells me that the memo to subscribers to Crawdaddymagazine is authentic, and it makes me wonder if I’ll ever collect the money that Crawdaddyhas owned me since 1969. Nah, I don’t think so. The attribution to William Lindsey Gresham is also authentic; Gresham was one of the great, tragic literary talents of the Twentieth Century and I commend his works to you. Other poetry in The Unicorn Girlis Michael’s own creation, and damned skillfully executed at that.

In this book you will encounter one of the world’s great natural story-tellers. I’ve worked with Michael on several projects in recent decades, and can tell you that his is one of the most startlingly creative minds I have encountered. We would be working along on a story or on a piece of nonfiction, and I would have thought or written myself into a seemingly inescapable literary cul-de-sac. Time after time, Michael would take over the helm and turn the narrative in a direction that I not merely hadn’t thought of taking, but hadn’t imagined existed.

And suddenly, we were off and rolling again

That’s what happens to the adventurers in The Unicorn Girl.

Now here’s another delight you can look forward to. I mentioned that I was saddened when I’d finished reading The Unicorn Girl. But on this occasion, The End is not really the end at all. No! Barely had I finished reading The Unicorn Girlwhen my friend Maurice Newburn surprised me by handing me a copy of Perchance, by Michael Kurland.

What was this?

I thought I knew all Michael’s books, or at least knew of them, and had read most of them. But here was one I’d never even heard of. I skipped home merrily clutching the book and discovered that, twenty years after the publication of The Unicorn Girl, Michael had produced a—well, yes, I’ll take a chance and call it a sequel.

Perchanceis another wondrous adventure in the realm of multiple realities. Once again people go blipping from one earth-variant to another. The characters aren’t the same as in The Unicorn Girl—or are they? Delbit and Exxa bear a suspicious similarity to Michael and Sylvia, and their leaps and scrapes are as breathtaking as those of their prototypes. The mood is, perhaps, a trifle darker, the tone just a little more serious, butr to this reader at least Perchancereads like Unicorn Girl II.

Perchanceis out of print at the moment, but if you wish hard enough—visit enough paperback dealers—cruise enough websites—you just might turn up a copy. Or, well, maybe Michael will see fit to bringPerchanceback into print. One can certainly wish

But for now you hold in your hands the one, the only, the original Unicorn Girl. It’s time to slip an old Harper’s Bizarre or Strawberry Alarm Clock LP onto the turntable, pour yourself a glass of cheap wine, take off your shoes and put up your feet. Then set fire to a little Maui wowee (if you’re so inclined—don’t tell anybody I encouraged you to break the law) and settle in for a trip to a wonderful half-real, half-imaginary era with Michael Kurland and The Unicorn Girl.

FOREWORD

to The Probability Padby Tom Waters

–Barbara Hambly, Los Angeles, California 2019

It was Michael Kurland who introduced me to Tom Waters.

Twice.

The first time was years before I actually met Michael. It was a central premise of The Butterfly Kid, The Unicorn Girl, and The Probability Padthat unlike most stories told from a first person POV, the name of the hero was the same as the name of the author: Hey, this is a book by Chester Anderson and, by gosh, when he talks about “I” he means himself, Chester Anderson, coffeehouse poet and science fiction writer, saving the world from alien invasion. When Michael Kurland narrates his adventures of going on a quest (with his good pal Chester Anderson) with a fair damsel to find her lost unicorn (and ends up saving the multiverse from destruction by intelligent green dinosaurs), he means him, Michael Kurland, retired spy and science fiction author.

And when he speaks of “… a tall, thin man in the robes of a mystic, with the erratically trimmed ends of thinning blond hair, sticking out from under his turban …,” he means his good friend, magician and mentalist and author T. A. Waters (who in this case had been inexplicably transported to what appeared to be Ogallala, Nebraska, in 1926). Tom later wrote about he, with the help of his good pals Chester and Michael, also saved the universe …

Even at first reading, I remember being pretty entertained byk their descriptions of one another. While Michael is generally described as an ex-spy and self-proclaimed expert on many things, while Tom is always a stage magician and hester is never without his recorder/has pipe and his I Ching, Chester’s description of Michael is rather different than Michael’s description of himself. Both are different from Tom’s description of Michael, while Michael sees Tom not quite as Tom sees Tom.

I never did meet Chester Anderson, who passed away shortly before I met Michael Kurland in real life. When the actual Michael Kurland—by that time a friend, living, like me, in Los Angeles—introduced me to the real-life T. A. Waters, Tom looked pretty much exactly like his description. He was at that time the librarian at the Magic Castle, a wonderful restaurant and prestidigitorium on a hill above LA—and also a well-known magician and the author of numerous books on mentalism and stage magic. At this distance, I have little recollection of our conversation, but I do know that I liked him. I subsequently met Tom at several science fiction conventions, and I always enjoyed his company. He was someone I would have liked to know better, and I was saddened to hear of his early death.

But even had I never met any of the intrepid heroes of what later came to be called “the Greenwich Village Trilogy,” those three books would still hold a special place in my heart They were first handed to me in the early 1970s by one of my dojo buddies, and I had never encountered anything like them. But as much as the zany fantasies themselves, it was the world in which they took place that drew me and draws me still. The world of the 1960s. The world I knew.

I suspect it’s why The Probability Padis my favorite of the three. It’s the shortest and has the simplest plot (“Aliens are attempting to take over the world yet again, how are we going to stop them?”). But while I thoroughly enjoy the others, The Probability Padis the book I’ve reread most often. To me, it strongly captures that place, that time.

Yes, all three of the stories take place in some never-quite-defined near-future, wherein it’s perfectly okay to smoke pot and become, as Chester says at one point, psychopharmacologically enchanted on a regular and recreational basis. (And to purchase the wherewithal to do so at any drugstore.) Our heroes take it for granted that they have to do occasional reality checks, particularly when the Evil Aliens get stoned and mentally transfer the effects into the brains or our unsuspecting narrators.

I don’t think any reader was ever fooled, nor were they intended to be. They take place in the late sixties, and that’s a world I remember—the way of looking at the world that I had and my friends had at that weird time when all of us were young. One can almost smell the friendly green whiff of—well, friendly green—mingled with incense, car exhaust, and the moldy scents of cheap New York City lodgings. (That’s back when there WERE cheap New York City lodgings.) It’s an attitude and a way of looking at the world that went far behond recreational substances, though they certainly contributed to the ambiance. Well, do I remember having conversations “so vague we couldn’t even remember what it was about duringit ..” When at one point Tom describes himself as wearing a neon paisley shirt and op-art jeans, I know that sort of outfit because I saw it on several of my friends. It was a time—and a world—where anything seemed possible an d much weirdness was accepted and tolerated.

God knows, I knew enough people who would greet the appearance of a tentacle Chthulhu-like monster with hysterical laughter.

The Probability Paditself, by the way, is either Michael’s Greenwich Village apartment or that of the evil quisling who is selling Earth out to the aliens, Jake Sheba. In either case, the place is familiar: mattresses scattered on the floor of the front room like lily pads (a room looking vainly for an orgy) and assorted six-legged wildlife in the corners. Like the Dude in The Big Lebowski, our three heroes give the impression of characters from one type of story who’ve been dropped into another genre entirely (which also happens several times in the course of the book). Chester, Michael, and Tom slouch amiably through a tale of dark doings, wandering off into conversations with lamps, TV sets, normie tourists from above 14thStreet and giant teddy bears (not to speak of guest appearances by Sherlock Holmes, Dracula, and squads of Tiger tanks). Though they’re aware that the situation is serious (you can’t really let Evil Aliens take over the planet), they’re not taking any of it particularly seriously.

After all, they’ve saved the world in the two previous books and are, in fact, getting a little tired of doing so.

As Tom remarks at one point, on the subject of alien invasions of Greenwich Village, “Around here, who would notice?”

To which Chester replies, “Who around here would care?”

That, it turns out, seems to be very much the point, if the book can be said to have one. The baddies are defeated not in battle, but by the fact that nobody takes their invasion seriously. The overly regimented, authoritarian Triskans depend upon disorienting their victims, whom they expect to be exactly like themselves. Confronted by the Village humans’ free-form attitude about reality, they are stymied. In a way, it is the human imagination that defeats them—in one of the gentlest climactic battles, perhaps, in all of science fiction.

Like a lot of people, the Triskans just couldn’t cope with Flower Power. The sixties leaves them baffled. When anything is possible, nobody is thrown into panic and hysteria at the prospect of the impossible.

In its way, the definition of that place and that time.

That flowers-in-your-hair world couldn’t last—if it ever really existed at all—and it was all but gone by the time I first read the books in the much grimmer seventies. But it’s good to remember what it was like.

Thank you, Tom, for reaching in and plucking that world out of the time-stream so that we can go back to it for a little while now and then.

Wow, David, you certainly gave me a splashdown in august company! And… for the record… I never knew that you took a flying leap into the Gull as an utter novice. By the time I got to Mendo, you were lookin’ like a total pro. Shows what you can do when you put the mind to it. Like the man sez, there is genius in beginning.