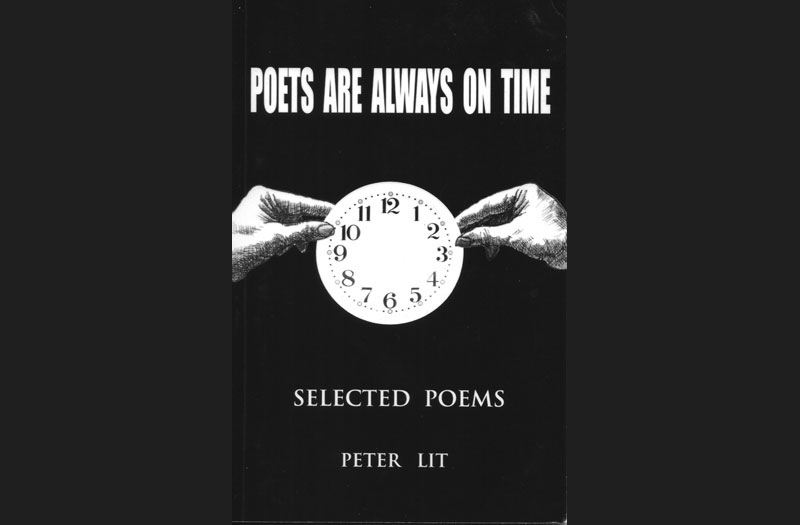

NOTE: Poets Are Always On Time by Peter Lit is available at Matson Mercantile in Elk, Gallery Bookshop in Mendocino, on Amazon/Kindle and directly from the author.

Peter and I are old friends. Not close, old. We both ran bars with live music on the Mendocino coast in the 70s and 80s. I withdrew from the insanity about 10 years before Peter. Competitors and friends. Unlikely but true. Recently we traded our recent “work”, my novel for his poems. I have now read his poems, all 103 of them, several times. Take it from me, they are worth reading. I offer this short review of his work. I hope you buy the book and read all his poems. Do it for me. Do it for yourself. Read them as many times as you wish. I intend to read them again and again whenever I feel like it.

These poems are from a span of 40 years, more or less. Most of that time the author lived in rural Mendocino County five miles inland from Elk. He has been building his home and feeding plants to gophers for over 35 years. Primary funding for these activities, ignoring the first 10 years, came from the Caspar Inn, owned and operated by the author until 1996. That experience is rarely alluded to in this book. Peter Lit

Peter writes in a sharp, clean style, mostly in free verse, sometimes with surprise endings. He is a natural storyteller. Some poems are crisp one or two sentence thoughts, arresting in their simplicity. They are arranged chronologically. It is not necessary to read them in order but I think the Confetti de Costa Rica poems are best read as a stand-alone unit.

Geographically the poems range from Hawaii to New Hampshire, from Alaska to Costa Rica and through San Francisco to Elk on the Mendocino Coast. The themes are wide ranging—birth, life, death, insanity, animals, birds, and solitude to name a few. Like many poets Lit writes about writing.

Karma

Ah—these creatures,

these creatures

of mine, which i

perforce,

own

have returned to visit.

They are insistent,

claiming their rightful place,

their proper share.

They were conceived and held

with such delight, once,

but now

they show another face

much like my other face

no

, the other one,

the one pride keeps from view.

To best understand the poems, it is useful (but not necessary) to dig a bit into the people and places that inspired them. There are many references to Buddhist thinkers and teachings (Lama Chime Tulku Rinpoche, S.N. Goenka, Mahakala). The “Islamic fishing guide; al-Khizir, the Green One, a.k.a. Kwaja Khadir” is integral to SO CLOSE I COULD HAVE TOUCHED IT. Charles Olson, Max Aub, e.e. Cummings, Carl Sandburg, and David Duncan are among some writers mentioned.

GATÉ GATÉ PARAGATÉ (gone gone everyone gone) is a gem of a poem in just seven lines (or less depending on how you count them). The title is derived from the Heart Sutra.

GATÉ GATÉ PARAGATÉ

On superbowl sunday

i followed a turtle as it swam offshore.

It was so beautiful,

moved so gracefully,

that i found myself beyond,

beyond,

far beyond, into deep water.

One poem I found very moving, REDEMPTION FOR CENTURION MINISTRIES, was inspired by a secular non-profit organization whose mission is to exonerate innocent individuals who have been wrongly convicted and sentenced to life sentences or death. I couldn’t help but think of the Dylan song Hurricane.

A few of the lines are reminiscent of Lao Tzu (the Taoist teacher) and his concept of “wu wei”—doing by not doing. For example: “I am silent in wonder” in FOR C and, in my personal favorite PORK CHOP: “As I learned to reach without reaching.”

PORK CHOP

Pork roast for dinner, sausage for breakfast;

we are getting fat from this unaccustomed flesh

My pig, my friend, we are feasting on your body;

bought for a drunken sow, your mercurochromed male body

turned you from ‘Daffodil’ to ‘Pork Chop’;

we cut off your balls, and raised you for meat.

As i learned to reach without reaching,

you learned to delight in the touch of human hands.

i shot you four times, in the head;

it took you twenty minutes to die.

i sat watch the time, thinking of hot afternoons

when I would go down to this boarded pen

and spray you with water while you scampered

in the mud, wagging your unscrewed tail;

remembering my return from a three-day absence,

how you grunted with delight, mouthing me gently.

In a fashion, killing you was the last defense

of my attachment to our pre-programed connection:

i wanted to ‘know’ where meat came from, now

i know. Believe what i can, think what I will

there are times knowing does not feel good to me.

These are good poems, thoughtful poems, poems to think on and come back to. I’ll end with a poem about the “cultural differences” between the Americas north and south and how they are reflected in language.

The Ticos use “vengo” to mean

i am coming, or

i am coming tomorrow, or

i intend to come

in the not-too-distant future.

Mañana means not now.

The line between the present and the future,

between action and intention,

is flexible, amorphous.

It is indicative of cultural differences

and the scope of possibility.

Thanks.

Peter-

I had no idea. What a wonderful surprise. Be well.

Thanks for reviewing these North Coast gems. It is amazing how we think the trees from afar are ‘better’ than the ones living in our back yard…

Peter, what a delight! I’m going to call Gallery Books right now and order a copy.

Thank you!

Erif