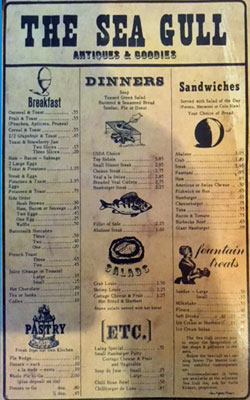

In October and November of 1995, Mike L. Evans wrote The Sea Gull Saga, a two part series for The Mendonesian, a local Mendocino publication. Part 1 of the series is transcribed below. Some of the original pictures in the article were not usable. Pictures of the old Sea Gull Cellar Bar were copied from snapshots taken during a wedding reception for the owners on June 8, 1974. Additional pictures were copied from a variety of sources. Part 2 of The Sea Gull Saga will follow in another post on this site. Additional posts relating to the Sea Gull Restaurant and Cellar Bar can be found in the FOOD section of Think in the Morning.

The Sea Gull Saga – Part I

By Mike L. Evans

The Mendonesian, October, 1995

“Over the years this property has had a number of owners. It was best known as ‘The Little Club,’ a bar/restaurant with a beer and wine license; and at one time was the Greyhound station. Originally the lot contained the old Stauer home, adjacent to the Stauer Blacksmith shop, which was later operated by John Chambers.

“The late Rev. Smith purchased the property, erected the present building in which he then conducted ‘Gospel Hall’ for a number of years.”

–From The Mendocino Beacon, April, 1962

The southeast corner of Lansing and Ukiah Streets. The heart of the village of Mendocino. A building that was the hub of community activity from the mid sixties through the late eighties. The place where people discussed vital topics, received jobs, gathered for unusual local events, such as Sunday Napkin Art, The Mendocino Dating Game, the infamous Sea Gull Gong Show, and a myriad of impromptu celebrations made possible by the environment provided by the owners of the different eras.

Owned by Mr. & Mrs. Clarence Mattison in the 1950’s, they sold the “Casa Mendocino” Mexican restaurant to Martin & Marlene Hall in April of 1962. The Halls renamed it “The Sea Gull.”

Marlene McIntyre started to work for the Halls in 1965 and worked at the Sea Gull in one capacity or another for the next 20 years, finally starting her own business (The Sea Gull Inn) in 1985.

Marlene McIntyre in old Sea Gull Kitchen

Marlene told me quite a few interesting stories while talking with her about the early days, the pre-David Jones era.

MARLENE: I moved here after marrying Jerry McIntyre. He was my second husband. My kids and I moved here when we got married in March of ’61. But I had previously moved here in 1956.

Martin and Marlene Hall owned the restaurant at that time and they were my friends, they just wanted somebody to relieve them in the kitchen. At that time Jerry just didn’t want me to work, because that was back when somebody told me what to do, I guess.

Finally then, we persuaded him that I really did want to work, so I started out working three hours a night, and that was back when the restaurant had breakfast, lunch, and dinner. It wasn’t the Sea Gull that most people knew as the old Sea Gull. It was just a coffee shop.

It had the counter, six tables along the windows there, and we did everything from these, even rented the Sea Gull Inn rooms from the restaurant.

At that time, too, we had maybe three dinners a night and we were really lucky because we did breakfast all day, people ordered boiled eggs at 9 pm.

When I think back on it, we had a lot of fun. We knew everybody that came in. We knew what they were going to eat before they even walked in the door. Like we knew Lang Chambers, she was an old school teacher, one of the older citizens in town, and she lived up above the barber shop. She always ordered a hamburger patty with cottage cheese. So after awhile we started calling that the Lang Special. Dr. Miles would come in and he always ordered a double hamburger patty with cheese and it might have had cottage cheese too, and that was called the Miles Special. And then we knew Big John, who had the Shell station over here. He’d come in and we always knew exactly what he wanted. We could even put it on the grill before they came in. We knew what they were going to eat. The minute we saw them, we’d say, “well, here we go.”

Marlene Hall in old Sea Gull Coffee Shop

It was just a whole different period in Mendocino.

M. What years were those?

MARLENE: In the middle sixties, like ’65. Martin and Marlene had the restaurant and they opened it in ’62 as The Sea Gull. Then they sold it, for a brief period of time, to Anita Klaus. They sold the restaurant and the Sea Gull Inn, which I own now, and also what is now the Mendocino Café. They sold all of that to Anita, and she really didn’t like the restaurant business. She ran it for a year, and then the Halls bought it back. By now, we’re in the latter part of ’64, and then I started working there in November of ’65 and I worked there until November of ’85, so that’s twenty years. Gosh, it would take me a book to tell you all of them.

M. When did they build the dining room, and the Cellar Bar?

MARLENE: Don Pollard did that, I believe it could have been ’65 or ’66, somewhere in there. What we knew in the old Sea Gull as the dining room and what became the Cellar Bar. The cellar was many things before it became a bar. It was a pool hall, it was a health food store, it was an antique shop. Gosh, I don’t think I can remember all the things it was.

Terry and Judy Johnson, Jerry, myself, and Martin and Marlene went to San Francisco and we visited the Marrakesh Restaurant, and decided that was a good way to decorate the Cellar Bar. We went to auctions down there at Butterfield’s.

You were here when the Cellar Bar was happening.

M: Oh yeah, the first time I ever got drunk in Mendocino was there.

MARLENE: Everybody got drunk there. I remember when the Dirty Bird first came in. Tony Miksak made it, and I was not much of a drinker, they were trying out these Dirty Birds, and so he made it, and I tell you what, I could not get off of that stool, I thought, “Good God, how am I going to get home?”

I don’t know if you remember all the funny stuff that was down there, from the puffer fish, and the rhinoceros foot, to all kinds of stuff that used to just make us wonder what Martin was thinking.

M: I remember the puffer fish and the heads on the walls.

MARLENE: The oriental rugs were covering the seats, and then they added the stove down there after the fact because it was too cold down there in the wintertime.

Entering the Old Sea Gull Cellar Bar from the front door

M: Did you notice any particular era when there was an influx of people who were kind of getting away from the city, before the hippies showed up? People not so much dropping out, but just wanting to get away from urban life?

MARLENE: It was people trying to find a style of living, and people wanted to get away and they loved Mendocino because they could just be whoever they wanted to be and nobody cared, and they still don’t care.

M: Oh, there were a few, I understand who did care.

MARLENE: Oh, I’m sure there were, I could name a few that did care, but I don’t know, when you think back it was kind of funny.

M: The Sea Gull was changing with the influx of people who came here …

MARLENE: It changed. Actually, I don’t think it mattered that the people came, I think it changed because those of us that were here, we changed too. I wasn’t any longer what I thought I was always going to be, just a mom and a wife. I wasn’t becoming that any more. My kids were all growing up here. Just like the Hall kids, they had to help clean the squid or wash the potatoes before they could go play. It was like a family, it wasn’t really like a business.

M: That seemed to carry over when David bought it.

MARLENE: When David bought it, nothing really changed, because David had the same attitude that the Halls had, and of course, he inherited the whole crew. By this time, I was doing a whole lot of stuff.

M: You were kind of running the place.

MARLENE: I did, kind of. And David was learning, he worked in the kitchen, and Martin too, they were not beyond working, they worked right along with us. If the dishes needed to be done, they did dishes.

When David bought the restaurant, that same attitude carried over that it was just a nice place.

I don’t think that feeling could ever happen again. First of all, everybody’s changed. We wouldn’t be there. There was myself, Lorna Young, (now Chance) and then Julie Calouro came on later, there was Cherie Christiansen and Max Salkin and Dancing Water, and so many more people.

But there’s more than one change that this restaurant went through. It seemed like every time we got a new chef it was going to go in a new direction, so we thought but it always went back to being the way it was.

M: Almost like the gravity of everybody saying “No, we want it to stay the same.”

MARLENE: That’s exactly how it was. We couldn’t get away from the steak sandwiches, which were wonderful, not that we wanted to. The good hamburgers—nobody makes those like we did then. I can try to make them at home, and they’re still not the same.

M: Is there any one thing that stands out, like when it burned?

MARLENE: Somebody came and told me in the morning that the Sea Gull had burned, and I thought, “Oh, my God, now what? Oh, it can’t.” It was like somebody dying, you don’t think that they’re dead, you know they’re going to be back again That’s just how it was. I remember sitting on the barbershop steps looking at that and I thought, “Oh, it will be back.”

Sea Gull Fire, Bill Foote Photographer, courtesy of Bruce Levine

And it did, it came back and it was okay. In fact, it came back even bigger and tried to be different, but it still went back to the old way.

Sea Gull Fire, Bill Foote photographer, courtesy of Bruce Levine

M: Because of the room available then it seemed to be a much homier place.

MARLENE: First of all, the barrels that were in the middle of the dining room were gone.

Everything changed. Of course, it had to change. Then the dumbwaiter came in. Doc Miles thought we were getting a little fancy there, though I don’t know that we were.

M: Rides for a dollar.

MARLENE: Yeah, rides for a Dollar.

M: I was just in the restaurant and the house yesterday. (now the office and old Sea Gull Bakery)

MARLENE: Oh, you were? I haven’t been in there. It gives me strange feelings when I go back in there, because it isn’t a home anymore. It was somebody else’s home and so it had somebody else’s feeling. I think I always felt too, that when people came in through the dining room door, that they were coming into my living room. In reality, they kind of were, because I lived there.

M: What was nice about it was that you still kept that family atmosphere, the hominess of it. As everybody said, it was like going down to the town living room. I think that had a lot to do with how you ran things.

Moving up to David selling the Gull, had you guys talked about it, had he said he was getting tired?

MARLENE: I knew he was going to sell, I think that I knew that things were going to change, depending on who bought it. And they did change. They changed a lot. Not that it wasn’t okay, its just that it didn’t ever come back after the change of ownership because they (Jim & Rochelle Marquardt) were two totally different people. They wanted to do their thing, which was fair, they owned it. Its just like here, I can do whatever I want to do here.

M: Jim Marquardt sort of had an idea of how people felt about it but he didn’t really, and he had no idea that people felt it was theirs and they should have a say in how it should be run.

MARLENE: Yeah, he didn’t realize that. And the thing about it is, in The Sea Gull as I knew it, everybody from the customers to employees, didn’t mind telling me what was wrong, or what was right.

For instance, it was okay for everybody to sign their tags. People would come in and they’d run credit. And we knew they were going to pay.

You wouldn’t do that today, anywhere. Well, you might at some places, but I doubt if people would do that anymore.

It was difficult for all of us who worked there after it changed ownership. I think that we always thought it was going to maybe be the same, but we knew it was going to be different.

M: Did you stay on to kind of ease the transition?

MARLENE: Yes, I did.

M: Did Jim & Rochelle ask you for any advice, or anything at all?

MARLENE: No. They came in and knew what they wanted to do. I think they might have been open to advice, but I felt that it was theirs, and I think I knew it was going to change. So consequently, I knew, when I saw the changes that were actually happening, that I couldn’t work there any longer. I couldn’t because I felt that it had worked for so long the way that it was, that to change it drastically right away wasn’t going to work. If you make a change it needed to be gradual change, it didn’t need to happen like it did.

M: Like the Sayers did when they took it over?

MARLENE: Yes. And if it starts up again, I’m afraid that the whole town is going to feel like, “Oh, good. Now maybe somebody is going to bring back The Sea Gull.” But which Sea Gull do we want? Do we want the one that we all knew and loved? Or do we want the second one, or the third one? Or do we want somebody to do something totally different? And that’s what I think, that’s what I hope.

M: I think that somebody will. I understand that the people buying it at this time are some locals and some non-locals, who do not intend to run it, they just want to lease it.

MARLENE: I hope they put the coffee shop back in.

M: The coffee shop is definitely missed. The town needs somewhere you can go and have a little breakfast in a coffee shop type atmosphere.

MARLENE: The other thing that happened was our breakfast really dwindled down when all the bed and breakfasts came in, including the Sea Gull Inn. Because all the B&B’s serve breakfast. Consequently there is not much of a breakfast trade left, except for the local people who come in and I don’t think that would support us. It would support someone if they were really good.

I’ll tell you when we had the most fun actually, as a group, was when we weren’t working. Cleanup. David would close (Martin and Marlene would, too) every January or so, and we’d get in there and just break our buns working so we could get everything clean in a week and reopen. Somebody would cook and bring us some food and we had so much fun doing that, and yet it was working. I remember this one guy, his last name was Vargas, he was supposed to paint the men’s room, and he did. He painted the toilets and he painted the sinks and he painted everything, and we had to go in there and take every bit of it off. It was really funny.

M: I remember Allison Browne at the time. Her first job was working as a bus person.

MARLENE: That’s right, and I remember she kept asking me when she was going to be able to wait tables, but she was too good as a bus-person (laughs) and later she worked here quite a while as a bartender. (see Feature photo in the next blog)

Another person that comes to mind is Danielle Belinger. When she came and applied for a job, and in fact every time I see her I think about this, she filled her application, when through all the proper whatever, and then she said she was a professional waitress. I said, “A professional waitress, nobody’s ever told me that, you must be good.” She got the job, and of course she was very good as a waitress. But she was the only person who ever applied who said she was a professional waitress.

M: She told me years later, when asked to fill out the job application, she said “I don’t fill out applications, I’m too good, I’m a professional waitress.”

MARLENE: She very well could have said that to me, but I think she did fill it out, but that’s exactly what her attitude was, she was a professional waitress.

Then I had people tell me that they’d worked at some of the big places in San Francisco and the truth of the matter was, they had never waited tables, but they wanted the job. You could just watch them and you could see that this person has never waited tables in their life. No experience at all.

I remember Tony Miksak and Cory Wisnia used to buzz me from downstairs, “Marlene, I need you down here, quick.” And they were having problems with somebody too drunk, and so I’d go down there. I never had any problems with anybody. I’d just say, “You guys gotta leave, and it’s time to go right now.” I remember Philip O’Leno, he was drinking, he intimidated everybody, but all he would do was just get up and go out the door, maybe mumble, but he’d leave.

I don’t know if they were just shocked to see this woman, I don’t know what these guys thought, they probably thought, “Oh, God, what a bitch, I can see why she’s doing this.” Actually, I wasn’t but that was my job, you know? That was my job, and I really didn’t mind it because it made the Sea Gull work. I think everybody respected me and all the employees, it didn’t matter how mad they would get at me, they always listened.

M: What do you think you miss, if you miss anything about it?

MARLENE: Oh, I miss everything about it, oh yeah! I’ll tell you what I missed was the socialness. I’m really not a social person outside of where I work. You don’t see me at Caspar, you don’t see me here and there, I’m pretty private, but this business that I’m in right now, and The Sea Gull gives me all the social life that I need.

M: Was there a period where people were more bizarre than at other times?

MARLENE: Oh, my goodness. There probably was a period of time when a lot of people were bizarre. But they all fit. And to work at the Sea Gull, if they didn’t fit, they either had enough sense to know it and would quit or I would just have to kind of say, in the best way that I could say it, that they just weren’t cut out for this kind of work. I don’t think I ever fired anybody and told them they were bad, but there’s a lot of people who were just, I don’t know if they were just too intelligent, or they just could never be a waitress, never in their life.

M: Like Carl Stephens?

MARLENE: Yeah. Like Carl? He was a bit bizarre, but I still loved him.

M: Were you aware at the time beforehand, that he was going to come in and wait tables, dressed as a Sea Gull Waitress.

MARLENE: To be truthful with you, I don’t think I did, because I wondered how I was gonna handle this one. Then I thought, well, its okay. And so he did. Because when he first came in, I thought, “Oh my God, now what? What am I going to do?” And the more I thought about it, the more I thought, “Well, I guess it’s okay. It’s okay.” But Carl was a special person.

I think that almost everybody in Mendocino who was a resident has worked at the Sea Gull in one way or another, I’m sure they did. Everybody became real special.

M: David told me the only reason the Sea Gull was what it was, was because of the people.

MARLENE: That’s true, that’s exactly it. It’s because of the customers that we had, and the tolerance that they had, too, because the service wasn’t always that wonderful, but nobody cared. We’d have people waiting up in the bar, tourists and locals, for an hour, to be able to eat there. And nobody cared. Nobody would hassle you, it was just the way it was.

M: Some of the dinner parties that I went to were pretty wild.

MARLENE: And our Christmas parties! Did you ever come to any of our Christmas parties?

M: I went to several. I even sat in with the band a couple of times.

MARLENE: Yes, you did

M: People would say, “Well, you need a date who works at the Gull to go.” And someone else would say “You can be my date. What’s a Christmas party at the Sea Gull without you?”

MARLENE: And what is a Christmas party without people trying to break in, pop in and be a party crasher? Like Danielle, for instance? Do you remember Danielle?

M: Cuban Danielle?

MARLENE: Is he still around?

M: He’s in Honduras.

MARLENE: He is, well, good for Danielle. I’m happy for him. He was another one, you know, he’d always come, and he was never invited, but he was always invited. He just knew he was going to break in.

Whenever someone would be acting rowdy in the bar, and they needed to be escorted out, I’d go up there and I’d say “You guys, you gotta leave.” And I always knew there were guys up there like Danielle and Billy Watson and all those guys, they were gonna stand up for me. Nobody would ever dare to say a word to me, because those guys would have been all over them. Even though I had asked them to leave, too, at some time or another. And they went.

M: Well, I think it is as you said earlier, it’s the respect that they gave you.

MARLENE: That’s what I think it was.

M: Do you remember when Bob Avery was bartending?

MARLENE: That was always fun, too. It didn’t matter who was bartending downstairs, it was probably always a good time, don’t you think?

M: Oh yeah, I was there having a good time the night it burned down.

MARLENE: But that next morning, it was so sad.

M: I was in Albion when I heard, I said, “Oh no, that can’t be, I was just in there.” We drove in right away, and we saw it, and the firemen were still working on it.

MARLENE: I think that was probably one of the saddest times that I can think about in my life up to that point. Of course, since then, my daughter Angie died, that’s now taken precedence over my life.

But the fire was really sad. Because we also knew that the old building was never going to be the same. Not that we even wanted it to be, but all the antiques in there, all the years and years of collection and all the memories that kind of went with that.

Old Sea Gull Cellar Bar

The Cellar bar down there had a whole ambiance all its own. It was like it always needed a good cleaning but it never got it.

M: It always reminded me of what I think an American opium den would be like.

Old Sea Gull Cellar Bar

MARLENE: That’s exactly it.

M: You would go down and people would just be lying back in the chairs with a smile on their faces.

MARLENE: And that was in the days when nobody cared what people did as far as their habits.

There was a little office where the liquor room is upstairs, and you’d go in there, and people in the hallway never thought you could hear what went on in the hallway, but you could hear everything, all the deals.

If there is one thing about The Sea Gull that I feel, it is that it meant too much to people.

……………..

Interview with Dick Barham

Mike: What years did you work at the Sea Gull?

Dick: I worked at the Sea Gull fro 1975 to 1977. I started washing dishes there. An opening came up in the old Cellar Bar. Bill Bradd was moving on, so he kind of broke me in down there.

M: Didn’t Bob Avery break Bill Bradd in?

Dick: Yeah, Bob was always there on call. There was Bob Avery, Bill Bradd …

M: … and Tony Miksak?

Dick: Well, Tony came a little bit after I did.

M: Is there anything that you remember that stands out that’s funny about working at the Sea Gull, or what it meant to everybody?

Dick: It certainly meant a lot to a lot of people. The town was still relatively small, not so many businesses, everybody had their eggs, potatoes and toast for 95 cents in the morning and then headed out to do whatever they did. It really was kind of a small town USA kind of meeting place. Now this goes on in the bakery, places like that. But we’ve all heard that everything kind of revolved around the Sea Gull. I don’t know how that applies to each and every case, but I think everyone stopped by for a short time at least, every day, it seemed. The other thing that was funny was how many people really worked there. I think the payroll was about 50 people at any given point in time.

Old Sea Gull Cellar Bar

I can’t imagine how many of the local kids worked there at the Sea Gull at one time or another while they were going to school. As you and I know, most everybody we know worked there at one time or another.

As for memories, yeah, there are lots. There were lots of characters in town.

M: Did you notice a tremendous difference from he pre-fire to the post-fire Sea Gull?

Dick: Probably. (laughing) Most definitely there was. I think there was just a natural change in the conversion of things. By the time the Sea Gull was rebuilt, everything moved upstairs. Certainly a lot of the charm and memories were gone, so you have to start a kind of new tradition. But I think it was a time when the town was going through a real resurgence of being discovered, a lot more people moving here, which in certain respects, took away some of the charm, the ambiance of the place.

M: It seemed to me that the attitude carried over very well from the old Sea Gull to the new Sea Gull, the feeling, the atmosphere.

Dick: It did, but the thing that I did notice though, was that a lot of the people just seemed to disappear. Quite literally, although I didn’t work at the new Sea Gull, so I didn’t know what the clientele was during the course of the day, before happy hour, during happy hour. Because during the happy hour days of the Cellar Bar, it was kind of fun, kind of crazy, total mayhem. There was certainly a group of people who would come in just for that, which did test your skills a little bit, as far as, A: keeping up with them, and B: making sure that, “Okay, that’s enough.” You kind of ended up babysitting these people sometimes.

M: I know that your were part of the happy hour crowd, later, on the other side of the bar.

Dick: No, I uh, no, I don’t think that, no, can we erase this? That’s not true. (heavy laughter)

M: I’m not saying you had to be babysat, but you must have noticed that sometimes there were people four deep at the bar, yelling at the bartender to get them drinks.

Dick: Yeah. One thing I do recall, but in the old Cellar Bar, there were times when, you could just hear a pin drop in there, and then of course, you’d wait until a play got out at the Art Center and it was wall to wall. I don’t know what the occupancy rating was for in there.

M: I think about 20 people. (laughs)

Dick: Yeah, but there were certainly a lot more than that. At eleven o’clock, the gals from the Heritage House would get off and they’d come in, let off a little steam, then a show would let out, and that place would literally be wall to wall, and I’d be the only guy there. In those days, I don’t know if it paid to have help, or didn’t pay to have help but, it got a little crazy at times as far as trying to keep up with the orders. But the main thing was, it was okay, everyone was pretty cool about it. It wasn’t a beer and bloody nose mentality. It was good.

M: You made my first Dirty Birds.

Dick: Birds?

M: Of course, I wasn’t buying them. Somebody bought me three one night. I finished the first one and a half of the second one. Before I finished the second one, they bought me another one, I never even touched that one. I was too far gone at that point.

Dick: Well that probably shouldn’t be put in print.

M: Oh well, no, this is just between you and me, Dick.

Dick: Oh, good! Okay, Mike.

M: The Dirty Bird was almost the famous drink of the Sea Gull, wasn’t it?

Dick: I think it was.

M: Do you remember who made that one?

Dick: Yeah, I did. I did it all. It was kind of my idea, I talked to Dave, I said, “Hey, lets have a Happy Hour here.” Not that we’re going to encourage putting people into a state of obliteration, but it might be good for business. I can’t remember the circumstances, but we came up with some kind of concoction made of vodka, tequila, Kahlua and half and half in a blender strained in an eight ounce glass for a buck-fifty. So, we used to make as many cans of those as we could—this was on Sundays—for one particular group. When the heads of the wild animals started being removed from the walls we kind of said, “okay, last call.” Time to put that one to rest.

M: It provided a little more room when the heads started coming down.

Dick: Yeah, you could wave your arms more.

M: And stand up and not hit your head. Is there any one thing that stands out from those days, more than anything else?

Dick: I don’t know. That’s a tough one. I think, as you ask the question, the thing that comes to mind was that it was the kind of job you looked forward to because there was always something unexpected that was going to happen. When the door opened, you could hear the reindeer bells, and you couldn’t see who was coming in.

I think what was kind of neat, is that, yeah, it was a job, but it was certainly an experience. People would come in and be a little bit different, then be a lot different when they left, so you discover things about them, and of course, it is true, that you become a really good listener, well, they can confide in you. And they really did. It was amazing, after just the one drink that they came in for, they would really start opening up. I guess it goes with the territory.

But aside from that, there were a lot of circumstances. There were funny instances that happened all the time, every night something funny would happen. A couple of times there were some very scary instances as well. But once again that goes with the territory when you’re dealing with alcoholism, which is the real downside of it, because if people don’t know when to quit, you have to assume that role.

As far as the instances, we don’t have enough time. I could go on and on. Without naming specific names, can I get away with that?

M: No, you have to name everybody. (laughs)

Dick: I have a list right here. Like the night I had to carry YOU out …

M: Was that the first time, or the third time? (heavy laughter)

Dick: That was the third time, I said, “Mike, there is a strike-three policy here; three strikes and you’re out.” (more deep laughter)

Remember Wiley Osborne? Well, Wiley was a big boy, he was about, as I recall, 6’6”, just under three hundred pounds. When he fell coming down the spiral staircase, from upstairs to downstairs, he got lodged in there, and it took us a while to get him out. The main communication from downstairs to upstairs was an intercom, which was interesting, because you’d hit it, and of course it would either be Marlene, or Dave, or even Cathy and we were so busy in there. They’d be ordering drinks over the intercom, and I’d be saying, “Wiley’s stuck on the spiral staircase … Was that a Bloody Mary?” and things like that happened a lot.

M: When it burned down, what was your feeling about it?

Dick: It was funny. It happened in the morning, as I recall, maybe even around 5 or 6 in the morning, and a friend of ours, Dale, stopped by and woke us up and said, “Dick, the Sea Gull’s burning to he ground.” She just went on, didn’t stop to make eye contact or anything. I went down there. I remember, Marlene was there, she was crying. There were a lot of people, and David was there, and I went up to him, and I can’t remember what he said, but you know David, “Well, there it is, you can’t do anything about it.” So you just worry about getting on with it. I’m sure as I feel now I felt a sense of loss.

M: I notice you’re choking up right now …

Dick: (Makes hacking sounds), no, I’m nervous. It was a loss, but the thing is, I wasn’t working there when it burned down. I had stopped working there for I believe, a couple of weeks.

M: You mean, like 2 weeks before it burned, you had just stopped working?

Dick: Is this gonna be some kind of legal issue here?

M: I understand that you were there the night it burned down, sitting in big chair .. (deep laughter).

Dick: It is a great feeling of loss, it’s powerful. I had that feeling, but it also numbs you, and you just become kinda real dumb.

M: Did you work on the new building at all?

Dick: From day one, Steve Scudder and myself were brought in along with David Clayton and his crew.

Dick Barham and Clifford Doolittle dismantle pipes after the fire, source: Mendocino Grapevine, January 13, 1977

There were a lot of people who worked there. There was actually a sign up sheet, and people would come up and sign up for a shift from 12 to 2 on a Thursday.

David Clayton

M: I remember doing some cleanup, gopher type stuff.

Dick: So it was a time. The one thing that sticks were the characters, the good times, learning from the bad times, dealing with human behavior. But just the fondness of reminiscing about that time, is the thing that sticks with me, because there’s other jobs that I have had that don’t have as much of an impact, or take up as much in my memory banks as this one.

M: How long did construction last?

Dick: I think it was perhaps six months.

M: It happened real fast, I remember. It seemed like it was open before anyone could believe it.

Dick: It came together pretty quickly. As I recall, we were doing it through winter, and it was one of our milder winters, it rained like heck every night, and then every day would be clear, so it really didn’t shut us down. That was the winter of ’76-’77, and that was a dry winter.

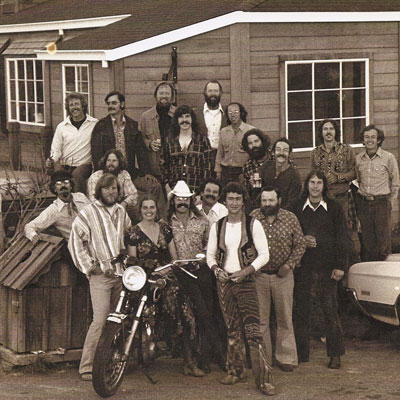

David Clayton and Crew, photographer Nicholas Wilson, courtesy Ilja Tinfo

…………

David Jones purchased the building/business from the Halls.

David: “I started business on January 1st, 1973. The deal was agreed to, signed, sealed and delivered in 1972.

In the fall of ’72 I worked there as an extra employee to learn the business because I was 25 years old, green out of college, never owned a business before, so I just said I want to start washing dishes, waiting tables and tending bar and figure out what I’m doing here before January 1st. That’s what I did until I actually took over. We never missed a beat, the place never closed or nothing happened. We closed on the first, which was New Years Day. We opened the next day on the second.

When Martin started the Sea Gull it was a counterculture kind of environment, in a way. From what I understand there were poetry readings, eclectic musical events that went on and things of that nature.

When I took over in January, the bar had a temporary license, so we were only open nine months out of the year. Very quickly, within a year, I traded licenses with another business on the coast and got a full year license.

I was young and I was terrified, but I was excited, and I felt that I had to be there when the place opened and when the place closed, and of course there was breakfast, lunch and dinner and a bar.

In those days we didn’t have any music downstairs except very occasionally, we didn’t have a Happy Hour, that started much later, the bar opened at 4 or 5 in the afternoon and it often closed at 8 or 9 at night. It was just kind of a service bar for the restaurant, and there wasn’t a lot of stuff going on. It was always open on the weekends. But even in ’75 there were slower nights when the bar closed early. We wouldn’t stay open when there was no one there.

M: When you got in there and the Cellar Bar was happening, did you hire new people? Was Dick Barham there before?

David: I hired Dick. In the first place, I didn’t fire anybody—immediately, anyway. I fired very few people over the years. Most of the people came and went of their own volition. I kept all the staff that Martin had. He had a great staff of people who knew the ropes, people naturally left, for one reason or another. I hired some other people. I hired bartenders, like Bob Avery, Dick Barham, Tony Miksak, and several others.

–Bob Avery

In that time before time, when the Sea Gull Cellar Bar really was in the cellar, a lot of Mendocino was imagined, shaped, prodded and produced by those who frequented the place – locals and otherwise. It was a strange den down there, wooden benches covered with oriental rugs cut to fit, brass tables that looked like gongs, overstuffed chairs, a very low ceiling, and crystals dangling from fancy fixtures (everyone thought they were amber until I washed them one night and discovered they were really clear glass deeply coated in nicotine brown!). The eclectic décor fit the clientele, or maybe the other way around, but it worked anyway, and most people seemed really happy with the inherent intimacy of the close seating and subdued lighting. I don’t remember any real “bummers” happening there – people generally took their disagreements elsewhere.

My tenure there began shortly after David Jones bought the place from Martin Hall. I don’t remember how it happened, really, but I spent a lot of time down there (it was my second office) and I think one night David was bartending, tired of it, and offhandedly asked me if I’d like a go at tending the bar. Talk about the fox guarding the chickens! With some magnificent restraint on my part I said I would consider it, and the next night I started. In those days the bar served primarily as a service bar for the restaurant upstairs, closing early as the diners thinned out (usually about 8 pm). Bartenders were required to wear a necktie and a vest, but the tie only lasted long enough with me to see me through a couple of days of training After some debate it was greed that I would at least arrive at work with a tie on, and after that it was up to me. Clip-on ties are great.

I never liked the idea of hustling folks out of the bar just because dinner was over upstairs, so I would take my time and let people linger over their cocktails as long as they felt like it. David Jones correctly recognized that extra revenue could be found by keeping the bar open late, and since it occupied a space separate from the restaurant it eventually stayed open until the regular 2 am legal closing. So I got to preside over the evolution of the Cellar Bar from a service bar to a nighttime hangout, and what a lot of fun we had there.

The only time it ever seemed to be almost too much work was when the Fireman’s Ball was held across the street in what is now a retail store, and 500 people would jam themselves into that little basement room during band breaks, wall-to-wall banshees all wanting their drinks at once. I have to confess to an occasional outburst of temper during those times, but otherwise I stayed pretty mellow, I think.

A lot of people got their first introduction to Mendocino in that bar downstairs having conversations with me and the patrons, and I like to think that I was a good envoy on behalf of the community. I enjoyed promoting the town, and not a few people told me years later that one of the reasons they chose to live in Mendocino was their recollection of those first hours in town. It always gave me a good feeling. It still does.

— Tony Miksak

The Cellar Bar was small, narrow, lined with overlapping reddish Persian-style rugs, old prints on the wall, dust balls, cigarette smoke, and in the winter, mud. After the seats at the bar filled, people lined the walls. I’d walk around with a tray of drinks and hear things like, “Nice buns!”

From my perch behind the bar I watched romances bloom and fade. They’d meet, seduce each other, become a couple. Then they’d argue, flirt with others have a fight, split up. The entire process frequently took less than a week.

There was the time my girlfriend left me for another boy. When she walked into the Cellar that night I couldn’t breathe. Tears burst out of my eyes and I had to leave the bar for the backyard. Things were more intense in 1975.

For some reason Metaxa brandy was the thing. We served more Metaxa than anywhere in the world outside of Greece. Coffee drinks were popular, too. Lots of Kahlua, lots of cream, very sweet and hot. Irish coffees cured a lot of flu attacks. We often had a room full of wide-awake drunks.

Twenty years later we’re drinking double mocha lattes. Same idea.

Everything I know about getting along with people, being fair and trusting employees, teamwork, respect – I learned from one person, David Jones. He had no idea he was teaching me. Later I was unhappy because I wanted to be the bar manager, a position David had never thought necessary. David wasn’t good at sharing his immense work load, and eventually he flamed out.

When the operation moved upstairs after the fire it was like lifting a rock and watching the bugs blink. The Oriental mystique gave way to big crowds, big space, loud bands. It was a different kind of fun. Harder work, even more smokey. But it no longer felt as if everyone who lived in Mendocino was in the same room at the same time.

Mendocino was like a summer camp in those days. It was stunning to see someone you knew walking around with a couple of old people named “parents”. Most days it felt as if we owned Mendocino and the rest of the world was very, very far away. There were a lot of fewer freeway miles and many more curves between civilization and Mendonesia.

And it was wetter. The rain went on for a very long time, and then there was a day of sunshine, and another month of rain and storms. People would emerge from their leaky cabins half-crazed with mold. The sound of rain dripping into pans was familiar music. Hot brandies in front of the stove at the Gull were the antidote.

I moved to Mendocino because of a broken heart. I came up to Mendocino to mope for a while and on the way back hitched a ride with a man who was writing the music for a movie being filmed here. I borrowed my brother’s Mustang, got the “gopher” job. I began to make daily round trips down to SFO. Film down, actors back.

By the time the movie finished I had a new girlfriend, a job at the Sea Gull, and a place to live one block from work. I bartended for six years, living on my tips, banking my salary. I fathered a child, did a rock ‘n roll show on KMFB and took weekly cello lessons in Santa Rosa. Plus I was friends with every last person my age. Everyone came into the Sea Gull at one time or another.

Crackling radio chatter woke me up. I joined the other stunned villagers in the early morning light gazing at a smoking black ruin. Image: Eddie from Mendosa’s in his volunteer fireman’s yellow coat, stepping among black planks in what used to be the restaurant. No walls, no roof. There was nothing anyone could do but wait for the rebuild.

Becky and I worked the night of the fire. I have no idea what happened. We closed as usual and the place burned down. Closest we could figure, someone left a lighted cigarette in the couch facing the Franklin stove. A small fire simmered most of the night. When David came in to open the kitchen, the outrush of hot air knocked him flat. Everything was gone in an hour.

It’s so sad and infuriating to watch the Sea Gull molder into oblivion these days. Maybe it should be leveled. Trying to reconstruct what was there won’t work. Maybe someone will install a coffee shop, restaurant and bar. Make the restaurant dark and break it up with a lot of walls and corners. Drape the bar with Persian rugs and build it way too small for the number of people who go there. Keep the prices low and the portions generous. And it still won’t be anything like the old Sea Gull.

And yet how incredibly marvelous the whole thing was.

— Lee Larsen-White

I worked at the Sea Gull for about a year and a half between 1976 and 1979, as a bartender. It was to be my shift the evening after it burned down. I remember two things about the Sea Gull distinctly: Happy Hour and David Jones. Happy Hour was a bartender’s nightmare, and a customer’s delight. Each day, teams of people would meet at the Sea Gull after work to have a drink and socialize. When I was working, I was often overwhelmed by crowds of people, often three or four people deep, all shouting my name and expecting me to remember what they were drinking. When I was meeting my friends there, I was always delighted with the hubbub. I liked knowing that there was somewhere I could go where I would know most of the people in the place.

The one most important factor in the Sea Gull was its owner, David Jones. David was the best employer I have ever had. He was concerned about his staff as well as his customers. He supported the community consistently, hiring talented locals to do paintings, woodwork, murals, signs, and music. He even recognized and supported napkin art. While other businesses talk about treating their employees as family, David actually did so. His warmth, patience and congeniality permeated the place. I think that when he left and new owners started treating their customers and employees as just that rather than as friends and family the community went into a state of shock. That was not, after all, what our town was about. We were all spoiled, there’s no question about it, and I will always be grateful to David for showing us how good it can be.

Since this article is so long, I’ve divided it into two parts. Part I ends at the beginning of David Jones’ interview, and then continues in the November issue with David, more input from former Sea Gull employees, and an interview with present owner, Jim Marquardt. The future of the Sea Gull is discussed after Jim’s interview. As we go to press, the Sea Gull is in escrow. –Ed.