[Click on BLUE links for sources and information]

Reports that say that something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know. Donald Rumsfeld

In 1979 Olga Andreyeva Carlisle in an interview with the famous Russian writer and dissident, Andrei Sinyavsky, asked this question: “Nationalism can be regarded as a natural reaction to the uniformity of modern life. But right now it appears that Russian nationalism is taking on a new, ominous political significance. I would like to have your thoughts on this subject.” Sinyavsky replied, in part:

… the Russian sense of self is becoming very assertive, very insistent. It takes on a chauvinistic cast. There is a lot of hostility toward the rest of the world . . .

Within the dissident ranks new passions are being born—intolerance, a renewed yearning for isolationism—that go with a vision of Russia as a theocratic state. I find such sentiments disquieting, even when they are expressed in very high-minded terms, as when Alexander Solzhenitsyn speaks.

. . . this view of the world excludes any degree of freedom. Personally I find it unacceptable regardless of who will win in the end. The Soviet camp may eventually win, or the West, or no one, but what does it matter? Only people matter, their feelings, the manifestations of human thought, the entire spectrum of human affairs. These are an end in themselves and should not be sacrificed to some abstract cause. Extremist ideas have dominated us too long, they have made too many victims already—our literature, our culture, not to mention the millions killed. That extremist ideas might gain popularity in dissident circles would have been hard to imagine only a few years ago. But here they are, growing rapidly among émigrés, and in the Soviet Union too. Andrei Sinyavsky, 1979 (The Hudson Review, Andrei Sinyavsky: Strolls With Pushkin, Richard Pevear, Spring 2017

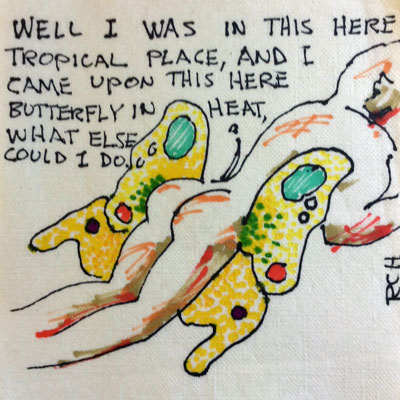

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

Sinyavsky’s answer resonates today when nationalism once again “is taking on a new, ominous political significance” in America and around the world. Does this matter? I think it does. In his 1946 essay Neither Victims nor Executioners, the French author, philosopher and journalist, Albert Camus, wrote:

We are asked to love or to hate such and such a country and such and such a people. But some of us feel too strongly our common humanity to make such a choice. Those who really love the Russian people, in gratitude for what they have never ceased to be — that world leaven which Tolstoy and Gorky speak of — do not wish for them success in power-politics, but rather want to spare them, after the ordeals of the past, a new and even more terrible bloodletting. So, too, with the American people, and with the peoples of unhappy Europe. This is the kind of elementary truth we are liable to forget amidst the furious passions of our time.

We share a common humanity but we are first and foremost individuals. As individuals we are susceptible to the fears and passions that can move human beings in dangerous directions.

The nationalistic surge today comes with a resurgence in “intolerance” and “renewed yearning for isolationism” and suggests that we have forgotten Camus’ “elementary truth” “amidst the furious passions of our time.” What can we do about this Herculean hydra that periodically rears its ugly head up out of the swamp?

Consider the road trip. “The road trip?” you say with a laugh. Yes, I’m serious.

Travel to other environments, cities, states, cultures, countries inhibits the poisonous sting of the hydra–shine a light on it and xenophobia cowers. In the Instagram era, the late Anthony Bourdain, chef, author and travel documentarian, showed us the meaning of authentic travel. Lucky for us this option stares us in the face at this very moment. It’s summertime, and summertime is one of the best seasons for a road trip (the others, to paraphrase Mark Twain, are fall, winter and spring).

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Jack Haye artist

I think it’s useful for Americans who don’t have passports and who haven’t traveled much to see, to at least get a picture of what people are like in these countries that we read bad news about all the time,” Bourdain said in a 2016 Eater Upsell interview. “So that when news happens, you have some clue of who we’re talking about. That they’re not just stacks of brown bodies, that they’re people. You saw them with their kids, you saw them cooking someone you know, maybe me, dinner. Anthony Bourdain

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

The road trip is an American tradition. In automobile-enthralled America if you have the interest, time and the money for gas there are unlimited options. There are other ways and places to travel—on planes, trains, busses, or just taking a walk. There are vicarious trips like reading a book or watching a travel/food/culture show like the ones that made Bourdain famous. Road trips in their various forms both real and imagined have spawned an enormous output of art including but not limited to written material, photographs, music, and cinema. Travel is a proven way of opening the mind and bringing us closer together, the perfect antidote to closing us off and tearing us apart.

Road Trip Reading List: Literature, Maps, and Ideas—click on the links to read.

The Obsessively Detailed Map of American Literature’s Most Epic Road Trips

Eight Incredible American Road Trips You Must Experience in Your Lifetime

Great Road Trips in American Literature

Ten Essential Road Trip Books That Aren’t On The Road

A Literary Road Trip Across the U.S.A.

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

It’s been 50 years since I graduated from Stanford. I mention this only because the university recently offered a class on The American Road Trip taught by poet, filmmaker, and author Kai Carlson-Wee (Text—The Open Road: Photography and the American Road Trip). It’s about time!

Carlson-Wee’s new book of poems, RAIL, is a beautiful and haunting rendition of the author’s train-tripping through America. For a preview, try his essay Train-Hopping Gave Me Back My Life. His beautiful poem, The Cloudmaker’s Bag, resonates with Think in the Morning as it reminds us of some of our past blogs. After reading the poem, you will never again think of a wanderer in the same way. [The Cloudmaker reappears in other poems in Carlson-Wee’s book.]

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, artist unknown

The Cloudmaker’s Bag

From RAIL by Kai Carlson-Wee

He shows me the camp stove he cooks with.

Ten-dollar poker chips. Crystals he carries

in small leather pouches, tied to his shoelace,

his belt loops to harness the sun. He carries

a matchbook, a cell phone and charger, a

lighter,

an old deck of playing cards with nudes

on the backs of them, needles and balled

thread,

thin strips of tinfoil wrapped up in two

yellow

Ziploc bags. He carries his own wife’s bones

on a necklace. Fingers them round in the

glow

of the shelter lights. Nuggets he dug from

the cremator’s shoebox of ash. He is seven

years homeless now. Living on handouts,

gravedigger jobs he has only been fired

from,

free meals down at the church. He carries

a homemade knife in his pocket. Dull gray.

Whetstone for keeping the blade-tip able

to break through aluminum cans. Watermark

stains on the handle from leaving it drawn

in the seaside rain. He carries a King James.

He carries a loose gold tooth on a string. He

Carries a phony ID in his wallet. Stranger from

Delaware, barely resembles him. Writes

down the names of the good eucalyptus trees.

Calls them his Darlings, his Leafy-green Loves.

He carries an old pair of foggy binoculars,

out-of-date passport, a penlight for writing his words

on the night sky. Something he picked up in Bozeman,

Montana. The stars are so clear there, they beg

for connections. For someone to map out

their infinite faces. To draw the invisible lines.

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

Another poet, my friend Bill Bradd, eloquently expresses his love of maps:

I’ve always been a map guy. At school I twiddled my time away staring at various National Geographic magazines. The WHERE OF IT was the question I wanted to know, and so my creative life’s work has been to record my surroundings, as I saw them, and to play free and loose with their locales.

Wherever a gap developed in the linear story, I would insert a PRESS-IN-ON-THE-MOMENT recording device which adds a certain three dimensionality to the place.

My first book of poetry, KINGDOM OF OLD MEN was a paean to the land of the large rock, the Precambrian Shield, where I was raised.

All my work deals with sense of place.

With this new work I have taken my mapping curiosity into my inner landscape and this book, Continent of Ghosts, is the result of this exploration.

—Bill Bradd

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

Travel inspires poetry and poetry inspires travel. Travel art, whatever the medium, includes the artist’s preconceptions as well as his journey. It reflects the artist back on himself and changes him. It changes him in a way that increases his respect for and his first-hand knowledge of other people and places. There is also the humbling factor of finding out what other people think of you. For the consumer of travel art, this can be a revelation.

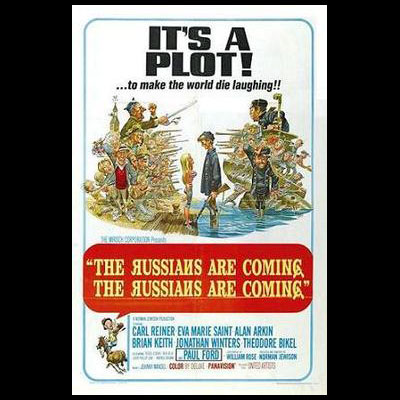

The Russians Are Coming: This 1966 movie filmed on the Mendocino coast is a great example.

Conspicuously absent from the links above are the views of famous Russians who spent some time in America and wrote about it. Given how much Russia has been in the news lately, it seems appropriate to make a note of some of their observations of America over the years. [Grigorij Machtet in the 1870s (The Prairie and the Pioneers; Frey’s Community), Maxim Gorky in 1906 (The City of the Yellow Devil and other writings), Vladimir Mayakovsky in 1926 (My Discovery of America), Ilya Ilf and Evgeny Petrov in 1935/36 (American Road Trip) and possibly the most famous of all, the author of Lolita, Vladimir Nabokov (see Nabokov in America: On the Road to Lolita by Robert Roper and Nabokov’s America by John Colapinto).

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard Artist

New York

by Vladimir Mayakovsky

You take a train that rips through versts.

It feels as if the trains were running over your ears.

For many hours the train flies along the banks

of the Hudson about two feet from the water. At the stops,

passengers run out, buy up bunches of celery,

and run back in, chewing the stalks as they go.

Bridges leap over the train with increasing frequency.

At each stop an additional story grows

onto the roofs. Finally houses with squares

and dots of windows rise up. No matter how far

you throw back your head, there are no tops.

Time and again, the telegraph poles are made

of wood. Maybe it only seems that way.

In the narrow canyons between the buildings, a sort

of adventurer-wind howls and runs away

along the versts of the ten avenues. Below

flows a solid human mass. Only their yellow

waterproof slickers hiss like samovars and blaze.

The construction rises and with it the crane, as if

the building were being lifted up off the ground

by its pigtail. It is hard to take it seriously.

The buildings are glowing with electricity; their evenly

cut-out windows are like a stencil. Under awnings

the papers lie in heaps, delivered by trucks.

It is impossible to tear oneself away from this spectacle.

At midnight those leaving the theaters drink a last soda.

Puddles of rain stand cooling. Poor people scavenge

bones. In all directions is a labyrinth of trains

suffocated by vaults. There is no hope, your eyes

are not accustomed to seeing such things.

They are starting to evolve an American gait out

of the cautious steps of the Indians on the paths of empty

Manhattan. Maybe it only seems that way.

Americans of a certain age may remember Khrushchev’s famous trip to America. “We have come to you with an open heart and with good intentions. The Soviet people want to live in peace and friendship with the American people.” Khrushchev greeted us with these words just three years before the Cuban Missile Crisis. Hey, all’s fair in love and war!

For something more recent and scholarly, try—Conflicting Views: How The Russian Public Perceives Relations With America

Or, this interesting piece on Russian Millennials—How Russian Millennials View U.S. – Russia Relations.

Or, How We See Each Other: The View From Russia

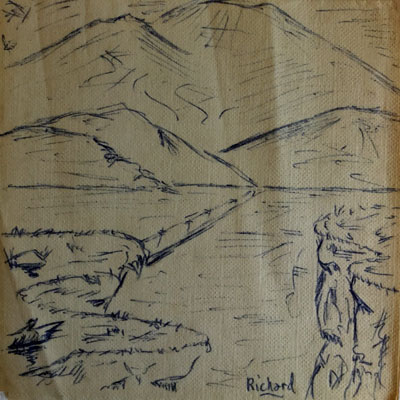

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Richard Albright artist

It is not always easy for Russians to travel to America. There was a period when the U.S. government banned Russians from a third of the U.S. (See: Russians Were Once Banned From a Third of the U.S.). And the Russian government has had on again off again restrictions. (See: In Russia, The Doors Are Closing). Russians come to America for many reasons including to have their babies. In the not too distant future it may even be possible to road trip all the way from New York to Moscow if a proposed “epic bridge” connecting Alaska’s westernmost border with Russia’s easternmost is constructed.

In Part II, Think in the Morning will provide some final quotes and experiences from the famous Russian travelers mentioned above–some hilarious, some outrageous, and some merely typical. I will end Part I with Nikita Khrushchev’s great-granddaughter, Nina Khrushcheva’s wonderful book on Vladimir Nabokov (Imagining Nabokov: Russia Between Art and Politics).

Nabakov loved the United States.

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard and KAT artists

He had an affinity for American parks. Already on his first trip he had visited Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Hot Springs National Park, the Grand Canyon, and possibly Petrified Forest National Monument (close to Holbrook, Arizona, where he recorded having captured a specimen). He also visited several state parks—in Tennessee alone he collected in or near Mount Roosevelt State Forest, Frozen Head State Park, and Cumberland Mountain State Park. While in Yosemite he again used the “accredited member” credential granted him by the AMNH (American Museum of Natural History). [See Nabokov In America: On the Road to Lolita by Robert Roper]

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

Nina Khrushcheva’s central point is that Nabokov bridges the gap between tsarist Russia (mystical, feudal and isolated) and the West far better than either the forced modernisation of communism, the chaotic shock capitalism of the 1990s or the authoritarian self-confidence of the Putin era. Nabokov, she says, presents the future of Russia for this century: a place that balances both the “indifference of democracy” and “heroes of kindness” such as perhaps his greatest character, Timofei Pnin (an émigré academic who is both besotted with America and at sea in it). [The Economist]

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

In 1953 Nabokov visited Ashland, Oregon where he finished his masterpiece, Lolita, and the first chapter of Pnin, a particular favorite of the Southern writer Flannery O’Connor who called the novel “wonderful.” Nabokov was an avid collector of butterflies, perhaps the most famous of all time. While in Ashland, he wrote a short poem based in part on his all-consuming hobby. I think the poem also shows how observant he was as a traveller (something further explored in Part II).

Lines Written in Oregon

Vladimir Nabokov

Esmeralda! now we rest

Here, in the bewitched and blest

Mountain forests of the West.

Here the very air is stranger.

Damzel, anchoret, and ranger

Share the woodland’s dream and danger.

And to think I deemed you dead!

(In a dungeon, it was said;

Tortured, strangled); but instead –

Blue birds from the bluest fable,

Bear and hare in coats of sable,

Peacock moth on picnic table.

Huddled roadsigns softly speak

Of Lake Merlin, Castle Creek,

And (obliterated) Peak.

Do you recognize that clover?

Dandelions, l’or du pauvre?

(Europe, nonetheless, is over).

Up the turf, along the burn

Latin lilies climb and turn

Into Gothic fir and fern.

Cornfields have befouled the prairies

But these canyons laugh! And there is

Still the forest with its fairies.

And I rest where I awoke

In the sea shade – l’ombre glauque –

Of a legendary oak;

Where the woods get ever dimmer,

Where the Phantom Orchids glimmer –

Esmeralda, immer, immer.

Wow! That’s all I can say….

Oh my. Hard to find the right words for how wonderful this piece was put together…interesting thoughts, good music and cool napkin art. Perfect.