Copied From Northglow, January/February 1984, Vol. II, No. 1, pp. 12-22

Editor’s Note: When Michelle Robinson sent us this article about the many-faceted Kelley, she explained in a covering letter the reasons for the introduction and conclusion and the way they were linked to the body of the story. They made sense and we suggested that she try to incorporate them as transitions. She tried—and tried—and gave up; they were too wooden, she complained, and interrupted the flow.

We finally decided to let the editor be the wooden one (no comments, please) and make the connections in this note, which borrows heavily from the author’s explanations.

Michelle began with Glenna, the grown woman (fully clothed), working through the teen-aged girls (fully clothed), to get to the mythic nude in Kelley’s sculpture “Tritogenea” in an attempt to dramatize the difference between the demeaning pornographic responses women of all ages and at any workplace get to their bodies and the respectful artistic treatment of the unclothed female form.

As for the conclusion: the piece, deliberately fable-like, with a classic small town diminishment theme (Kelley’s travails being an example of what many of the artists in this once “artists’ colony” are going through) needed some statement of celebration at the end. And the encounter with the whale—thousands of miles from Mendocino but in a recess of that same great ocean—says this: “no matter how cramped or crass our bucolic lifestyle is becoming, all of us here understand that we re still linked by the ocean and its creatures to a greater psychic expanse.”

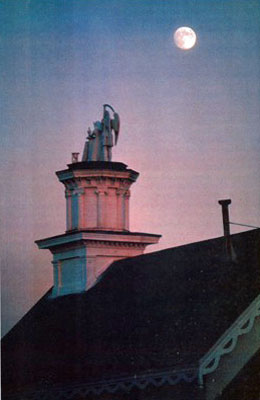

Mendocino Masonic Hall by moonlight. The famous century-old figures on top of the building have something in common with S.R. Kelley’s work. Kelley uses redwood and Eric Albertson, who built the hall, carved the crowning piece from a single redwood log. Completed in 1872, the building has been in continuous use by the Masons ever since.

Sculptor, Piper, Busker

By Michelle Robinson

Photography by Timothy Higgins

Long ago, over midmorning coffee at the Sea Gull, Glenna Hunter, garbed in baggy fatigues, rivets my attention with her latest attempt to find work.

Glenna is a fine carpenter. Mostly, she is hired to crawl under old building and shore up first-growth pier and post foundations. She has just come from a job interview with the town’s largest contractor. You would be hard pressed to find a man straighter in his attitudes or appearance. Yet he was the first (at the time, also the only) contractor to hire long-haired journeymen as they began drifting into Mendocino.

It is winter (this winter almost a decade back into our friendship, when dynamite Mendocino Country Women enjoyed their greatest repute) and Glenna, tired of the underbellies of buildings, is looking for inside work. She arrives punctually at the construction site with her tool belt, taps the boss on the shoulder, and asks to be put on the crew. He looks her up and down, then says bluntly, “I put you on, my men will keep their eyes on your tush all day and no one will do any work.”

Five minutes later, he is offering Glenna all the scrap lumber she needs to complete a shelter for battered women she is building on her own land.

“Don’t tell anyone I’m giving you this stuff for that,” he cautions. “I’ll never live it down.”

Glenna does this story mostly in pantomime. We are laughing and gasping too hard for it to be told any other way; two women—braced by the buzz of coffee room camaraderie around them—wising in hysterical unison the capacity for sudden, inscrutable, ironic kindnesses within the most barbaric men.

I never cease to find remarkable the interior resemblance between ourselves and other species whose lives are organized most like our own.

Like social pack wolves, we digest our food, drink, insights and rank more easily companioned. (Is anyone really comfortable eating alone?) At the Sea Gull each morning during breakfast, the Chronicle crossword puzzles are done communally across the tables—staving off future senility—much like neuroanatomist Marian Diamond’s old rats, whose cortical neurons increased in size and whose dendrites flourished, when they were kept in roomy cages with a dozen (no more) companions and challenging new playthings daily.

From the Sea Gull counter, one gets a glimpse of Mendocino’s matrix of casual cultural medicinals—none more therapeutic than our exchange of generic-Mendonesian tales.

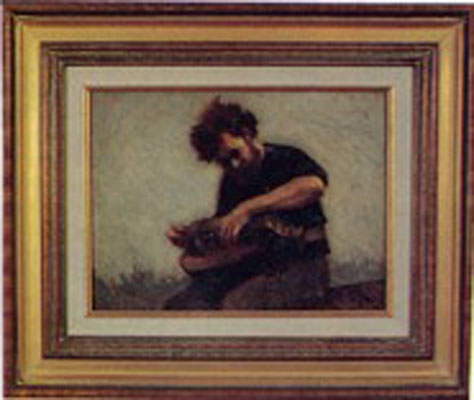

Kelly, The Hurdy Gurdy: oil portrait by Olaf Palm; in the collection of Ernestine Barrett, Riverside, CA

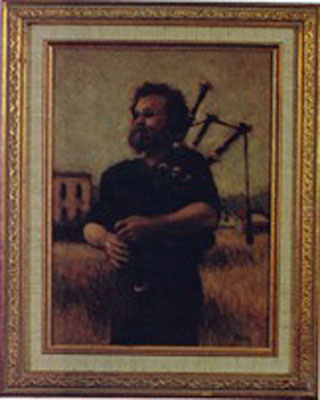

Kelley, The Pipes: oil portrait by Olaf Palm; in the collection of Don Robb, Fair Oaks, CA

There is an exchange peculiar to a story that is spoken that does not exist in the written word—a simultaneous synchronization of micromovements between teller and listener (we sometimes experience as enrapture) as the listener part of the universe alters to oscillate with the speaker. I think of it as a manifestation (at near distance) of Bell’s theorem wonderfully summed by Nobel physicist Brian Josephson with these words:

“When a polar bear jumps into Arctic water, in some weird way it may cause a train wreck in the south of France.”

Some bridge the difference between what is spoken and what is written with music. Jed sits in the pickup parked in front of the Mendocino Laundromat reading the Chron sports page. Loud L.A. rock blasts from his speakers, but his nose and shoulders move—just barely perceptibly—to the sports. He startles when I address him through the open window. Tells me he watches a movie when he reads. As I leave, he leans over: “Know any kids looking for work? I could use some help … (pause) … manicuring.”

Jed is a grower. The code word is uttered with a meaningful look.

“I like to provide employment opportunities for local kids when I can,” he adds, quite seriously—in the same concerned, paternal tones and phrases I have heard ring from the mouth of the manager of the Fort Bragg Chamber of Commerce.

Later that week (now almost a decade after my conversation with Glenna), I sit down at the coffee table at the Sea Gull already occupied by two 16-year-old girls. Both work as maids during the summer. One works for a swank bed and breakfast inn, the other for a more yeoman lodge. They are exchanging stories of sexual harassment: the men who enter the rooms silently and grope at them from behind. The ribald suggestions other male guests make: what they would like to do to their bodies in the rooms they clean on the beds they make. Teenage girls do not file sexual harassment suits. They handle these situations with their elbows, or profanity, when profanity suffices. And they nod into each other’s recountings.

Across the street, the Mendocino Shell Station is metamorphosing into Ghiradelli Square. The gas station is closing. The gas station is the only business in the past decade to be owned and managed by a youth who graduated from Mendocino High. Local teen-agers do not work in the shops. Sometimes they bus. Sometimes they even prep-cook. More often they make beds and stay out of them. Jed’s offer is generous, if not tragic. Mendocino is a wonderful place to raise children when they promise to grow no older than 15.

…………………………….

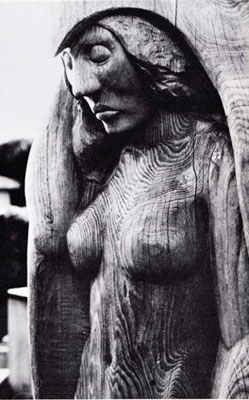

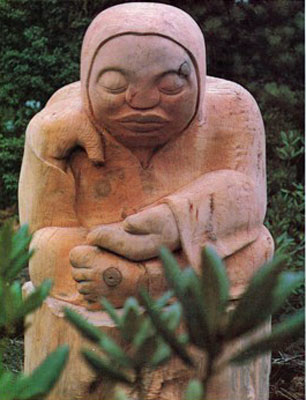

Up the stairs, above the Sea Gull restaurant, is the Sea Gull Cellar Bar where children are not allowed. A huge (12-foot by 4-foot by 3-inch thick) bas-relief redwood slab carving, “Tritogenea,” dominates the southern wall.

Three figures stretch across the carving. One sits, the others sprawl, androgynously, at either end—one cloaked in rough-hewn winged extensions of its arms.

The central figure is a woman of indistinguishable race and time. Gauguin in that respect (as is the coloration of the redwood slab, her black stained hair, the fill-in flora). She sits spreadeagle in a visually strong position and just by gesture, she is moving strength around—gesturing with it, hamming it up, receiving it, displaying it. She is the power figure (also the only one unclothed); a mix of primordial vigor and pagan ceremony—slightly savage in her openly displayed pubic nudity.

Naked, she wears the horned headgear of earliest shamanistic significance. And this headdress is sublimely contrapuntal to the hats worn by the other two. The squatting figure on her left is decked in an elaborate fool’s hat~~which is what the horned helmet (and shaman’s role) reduced to during the time of kings, to become later the witch’s hat of the Inquisition, degenerating finally into the dunce cap punishment that lingered on long into the McGuffey classroom. The sprawling feathered figure wears the skulltight executioner’s hood.

I have always wanted to ask the sculptor if he was aware of this historic millinery progression as he assorted his symbolic accessories. Then forgot to ask when we talked.

The carver’s name is S.R. Kelley. There is the same cadence to all he does—his massive carvings, the music he plays on the bagpipes from the ocean headlands and on the hurdy-gurdy from the front porch at Gallery Fair; the way he tells a story, even the way he digs. Hypnotic strokes. Deliberately ambiguous. Mythic. Narrative. Explaining much without ever being indiscreet or confessional. Never going that far in a conversation or his art. You could translate it all into the same sine curve.

You can actually feel yourself phase-locking with Kelley as he tells a story, like pendulum clocks mounted side by side in a shop. That mutual oscillation has been called “rhythmic entrainment.” Perhaps the delight of a good story from a master story teller (or a tune from a fine musician, for that matter) is that the telling changes for a time what may be our own awkward pulse.

You must catch up with Kelley. I catch up with him as he is carving into a huge mound of pygmy hardpan, shoveling clumps of variegated red clay and subsoil into a wheelbarrow he has raised with two-inch blocks to fit his own height. Trotting the wheelbarrow down a lane to dump along the roadside before the rains come and turn the mix into a new, even harder, conglomerate. Trotting back to the pile. The land is transitional pygmy some two miles up the Comptche-Ukiah road in an area oldtimers once called “The Prairie.” The dirt is a private disaster left over from a septic tank the county has required him to sink into the impenetrable soil.

Kelley managed to live on his land close to 17 years, using a low flush marine toilet that drained into a hole he never saw fill in that time. Now that the septic system is in and the mound nearly leveled, the county insists he add $4,000 more worth of leach line. There are days when Kelley makes all of $5 busking. It is surely a Sisyphean task which comes across like an episode from Velikovsky as he shovels and hauls.

“I’ve been in Mendocino almost 20 years—a year less than half my life,” begins Kelley. “Found the land within three years and started building at once. Got the shell of the house built before I actually owned the land. The house wasn’t to be a house, it was to be a shop. And the guy next door said, ‘Don’t build a shop and expect to live in it while you build, because you’ll never have a house. And don’t put plastic in the window or you’ll have it in there for five years.’ Well, I took my last plastic out the eighth year. And I know I’ll never build a house. I don’t have the time.” He says this last indicating the pile of dirt with his shovel, then smiles and adds, “But I have four shops.”

In one of the four shops on his land where Kelley lives his backwoods equivalence of the starving-artist-in-the-garret existence, he carefully crafts hurdy-gurdies for an international market. He is an encyclopedia of good-humored hurdy-gurdy vignettes.

(Listen to Donovan’s Hurdy-Gurdy Man HERE)

“There’s a weird subject,” he commences. “I’ll start with the origin of the name. Hurdy is old Scottish for the shape of your rear end. So to hurdle a fence means to get your ‘hurdies’ over the fence. And a gurdy, as all fishermen know, is some sort of crank or winch. And some early hurdy-gurdies, of about the time they would have named it such, were dimpled in the back where the crank went in. So you can imagine how this slang term came about.

“That it’s obviously a slang term becomes apparent when you look at it well. Because there are other names for it—in every culture—more proper names.

The Bird Woman, redwood sculpture by Kelley

“During the last of the French kings, the time they called Arcadia at Versailles, they took to putting on little plays and everybody acted as though they were peasants—very clean and rich peasants—but they took up the peasant image. And it became quite the thing to play the hurdy-gurdy. Everybody had rhinestones and ivory and everything you could think of put on theirs. And the craftsmen were paid to do nice ones. So that caused them to evolve into a very fine instrument.

“When it passed out of favor, why then, it went back to the street in the hands of the blind beggar. And then what happened is, there came along the organ grinders, who would buy an instrument like a player piano—that is, a big box with a crank—and they would play this thing that was not playing at all. They would just provide the power. And since both people would stand in the street with their cape hanging over their instruments to keep off the dust and dirt, people didn’t know which it was.

“And if you take a fairly well worn out grind organ and you take a hurdy-gurdy the beggar hasn’t done anything right to in years, they both sound fairly bad—which gave the hurdy-gurdy a lot of bad press in some circles. It’s something that can go badly awry, much like the pipes, and everybody will hate it. But done right, it’s very beautiful.

“The problem with it is that it is difficult to accomplish. First of all, you must learn to hear it, and tune for it, and get all the drone. Since Bach did what he did to music, everybody’s gone for the fundamental. And nothing’s right except the fundamental. That’s why drone music sounds odd to the classically trained ear.

“Helmholtz back in the 1800’s said you can learn to hear up to 12 overtones. And in piping—and the hurdy-gurdy, which uses the same stuff, and Indian music—you don’t tune the fundamentals perfectly since on different notes—and even the same note on a different object in different string—it will come out slightly different. So instead of getting the fundamentals perfectly in tune as the starting point, you must tune all the overtones to have a harmonious halt.

“And not only a harmonious halt. There’s a lot of solo kinds of character you could have. And this is all limited by what the instrument feels like doing that day, according to the humidity, temperature, rosin and age of the strings; what you did yesterday; and, of course, your ear goes through some changes, so the sound itself propagates differently through the ear.

“Some days it won’t go. Everybody says, ‘Oh yes, that’s fine.’ But nobody dances. And other days, when it’s fine, but you’re not all that fine, everybody goes, ‘Boy, that would be neat if only you’d learn to play it.’ Or subtleties to that effect.

“And some days, everything is right and you make magic. You can bounce. You can feel the keys—the vibrations feed back through your fingers. And when it’s together, it’s like an army marching over a bridge all in step. It tends to make the whole bridge move.”

(Read more about the hurdy-gurdy HERE.)

All this Kelley speaks as he hauls and shovels. Listening to the tape later as I transcribe it, I can hear the metre of the work in the prose. Then thinking back, I realize that instead, he was pacing the labor to his syntax. And the longer he discoursed, the more effortless seemed his work.

There is a pause where he leans against the wheelbarrow, then a return to the shoveling and his voice.

“The two reasons for the pipes not being favorites are: first, they’re hard to get running and when they’re running poorly, they’re pretty awful. When they’re running mediocre, they’re fun. But when they are running great, some people do not like them because they’re inescapable. When they’re running great, they’re even worse because you can’t tune them out. You can’t say it’s bad. And you really don’t have any choice but to let them pull your strings. And people don’t like that. It scares them. Which is the ‘devil in the fiddle’ and ‘the devil in the pipes.’ That’s why some folklore runs down that line.

“I remember,” says Kelley, “the first time I marched to the pipes. I was marching back from a movie in the dark the first time I felt it. It makes your step so amplified. There can be 120 men all stepping at the same time and suddenly you feel 80 feet tall. You get that and you get a sense of oneness with people, even when you know it’s not true. But also it teaches you to obey commands without asking questions first. You just do it and that becomes Pavlovian—they hope.

“The pipes start so far back, they suppose in the Middle East, and went through things like the forerunners of the oboes. Somebody thought to put a bag on it so you could breathe without stopping playing, which is the whole point of that.

“Mine are Scottish pipes, made by Gillanders in his 51st year of making them. And he had taken over from his father in his 49th year of making them. So there is exactly 100 years of experience involved in making mine.

“The pipes sound much the same to me as I’m playing them as they sound to whoever’s listening. The hurdy-gurdy varies with distance and angle due to having tops and bottoms, but with the pipes, the sound is very close to the same thing. You might say I’m in the best position since I’m not biased toward chanter or drone. When you’re listening as you stand behind it, you hear mostly drone, and when you stand in front of it, you hear mostly chanter. The one difference is, your ears take on a different pressure when you’re playing, and that alters the sound. It has a slightly deadening effect. A lot of times I have to stop and swallow to clear my eyes.

“When music is working right, you don’t think about what you’re playing. You don’t really think at all. You just listen, and basically you’re intaking—consciously or sort of unconsciously. But obviously, you’re putting something out, so you’re just part of the circuit.

“I’m sure something is going on when I play out into the ocean. I haven’t seen the large sea mammals do anything. But one time I was playing back and forth to a little bitty frog in a puddle. He would croak when I croaked and stop when I stopped. The big guys might be more subtle. Certainly the seals seem to take it all in. The whales just keep on going by.”

Not all who journey to Mendocino come to entrain with the ocean and dance the cosmic dance. Often they are simply here for a day of 19th century timber town kitsch.

Kelley plays the bagpipes on the headlands for his own pleasure. He plays hurdy-gurdy from his perch on Kasten Street when it is his only available self-employ. I ask him how he sees his music altering the streetscape.

“I play my music on the Gallery Fair porch because it’s illegal to play on the street. You have to be on private property—with permission. And I expect someone will eventually get it together some day to make a law against that. Last winter I had to play to eat. A five-dollar day meant I could eat for two or three days.

“You tend to be repetitious. You tend to repeat not only the music, but the answers to all the questions as well. Your arms get tired. It does become work.

“Some ignore the music, couldn’t care less. Then there’s the kind that just like the feeling. They don’t have to know much about it or be particularly with it; they just sit down and hang out and decide that’s a fine place to be in town. And that’s always nice.

“There’s another kind that’s afraid of it. And afraid of the person behind it—and this includes locals too. When you start to play in the street, it becomes a reverse status thing. And the more you do it, the more you see people turning away. There’s a certain fear of involvement. And a certain idea about begging.

“Technically, to play, sing, dance, put on a show or whatever on the street for money, without any agreed upon price, is to beg for it. In England, to do something for it—in a show business sense—is called busking, and it’s been around for a long time.”

“Are you only there for the money?” I ask. “Do you get anything else?”

“I get practice. And it get me publicity. Occasionally, I sell an instrument, or get a job that actually pays. In the past I’ve done it to eat.

“To do it on the street every day puts you on another level of competence. It indexes through your mental computer more ways to access a tune and relate it to other tunes and different ideas about tuning. Ninety per cent of anything is perception—that is, if you can see it clearly, usually you can do the right thing about it. It frees my mind up for when I’m playing seriously.

“Playing long is good for you. Playing long gives you bigger muscles. Playing on the street isn’t necessarily good because you have to deal with a lot of foolish stuff and things that don’t make you feel good.

“In the end I noticed I was getting by on the money without it. And it was bad for my persona. That I was not presenting a good face. That I was going some harm with my playing. And I was wearing out my welcome at that spot. It was foolish to continue. So I decided to back off and wait until I really needed the money again—which does have an inspirational quality to it—and let people develop a nostalgia for the funny sound.”

Dusk overtakes our conversation. Kelley puts aside his tools. We sit on the embankment over cups of coffee, easing into talk about sculpture.

Tritogenea was begun on a bar napkin. Kelley then spent four days wandering about town. Drawing. Wandering. Drawing. He came up with 30 pages of elements. Switched them. Changed angles. Discarded.

“Finally,” says he, “it just went click. All of it as one thing came into place. And I showed it to both Davids (Sea Gull proprietor, David Jones, and designer-builder, David Clayton. Clayton, the most talented and emulated of the 20th century Mendocino architect-builders, died in an automobile collision on Dec. 22, 1983) and they both said, ‘Fine,’ and I ran right home and did it because we were all satisfied.”

It took Kelley three months to carve the sculpture. He worked the green redwood slab outside under a shed in the damp weather, for redwood cannot be worked dry.

Tritogenea was completed the day before the new Sea Gull (phoenix-like, arising from the ashes of the old building which had caught fire the winter before) opened. The stairwell would not accept the enormous bas-relief. Kelley squeezed it between the firehouse and the new building, hoisted it to the firehouse roof, removed one of the brand new porch windows and carefully maneuvered it into the Cellar Bar.

There was a 40 per cent humidity difference between the shed and the attic. And a 30 per cent temperature jump. Tritogenea cracked within the first week of its installation. The crack spread across the rough-winged figure, topping short of the most delicately wrought work.

“David thought it would fall in half and we both had lots of people advising us separately how to fix it. At one time David said there were so many people that knew just what to do that if I didn’t do something, he would put it in the hands of someone else. So I put two great big clamps on it. And then I went away.

“Monique worked the bar then and after a couple of months she said, ‘Hey, Kelley, how long are you going to leave those goddamn clamps on?’ I said, ‘Well, until somebody tells me to take them off.’ Three days later the clamps were in the stockroom. Monique had decided to take them off. The split hadn’t altered the carving any. You can’t clamp it together forever. And it would look bad to fill it in. So it’s best just to let it be.”

Tritogenea. The name of the Sea Gull carving induces as much perplexed musing as the sculpture itself. I’ve watched people peer closely at the small brass nameplate and wonder at its meaning.

Kelley won’t tell.

He discloses only that he came across the name in a book he was reading at the time, that the context has nothing to do with the carving, but the sound of the name sounded so much like what the carving looked like, he named it so.

I asked Kelley if he felt shamanistic as he was carving the piece.

“Oh yes,” he answers. “I always do to an extent. The thing about abstract art is that it is student work. People in art school learn how to put a circle and a triangle in an interesting position and that’s where they stop. Or they learn something about texture and color. And they stop. All these are merely technique. In that carving I used technique to show flow of energy. So you got that technique down. And if that’s all you had, it’s merely student work, which is what most art is.

“On the other hand there’s rhythmic capability in art. And it seems a shame to leave anything out. Mythic things speak to you very well. They drag up things that you may not understand and they cause you to be more alert. So the mythic element in that carving tends to awaken not only the intellect, it causes you to enjoy the aesthetics and techniques too.

“My point is not to tell people what to see when they look at them or to limit their ability to think when they look. Just let them look. And if it causes something in them to waken, that’s sufficient.

“So I can take the woman figure and mix it with strength and shamanism, paganism, savagery, funny hats, plants what have you, and it gives a little more weight to those mythic elements—to give people some sense of everything that is going on besides the workaday world. In a way, I like to think of what the gods and heroes were doing on their day off.

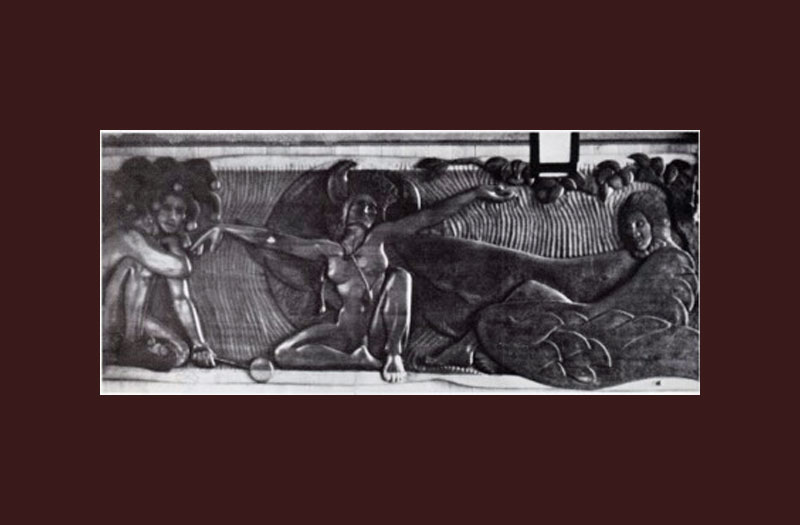

“I have a woman in a bird costume, a great big one, down at the Gallery Fair. She’s naked with this bird costume draped over her and that suggests the obvious pun of ‘the woman in the bird-day suit.’ She’s not particularly Indian, but you relate to that. My inspiration is all subliminal. I like to think of her as Thor’s favorite cheerleader going off to the showers after the big game.

“These mythic people went off duty from time to time. They went to bed. They took a crap. They had girlfriends other than official girlfriends. They did whatever they liked to do. Water ski. You could take it to that pop sense and show her water skiing, but that would cheapen it. So I try just to show them in a slightly different guise. Still it’s mystic. You might not know what they’re doing, leaving the question again. And if I leave enough questions, someone will start asking their own.”

I’m astounded by Kelley’s irreverent assessment.

When I first came across the Bird Woman, I recognized at once the creature of my favorite creation myth—a solitary female presence with hawk aspects gazing into the curved mirror of black space, poised to burst forth with the single scream of lonely ecstasy which brought forth all that became beings—indeed, an early version of big bang theory from the ancient white goddess traditions.

“Well, that’s here all right,” agreed Kelley. “All the myths made up in different places are all about the same sort of people or even the same person, and that’s one of them.

“This one happens to be finishing up the ceremonial aspect that imbued her with all that power, but still, she has to go off and have some refreshment, or give it up sometime. So I catch her leaving the field of performance an she’s a little bit tired, going off to have a drink as soon as she gets out of that costume.

“In most of my sculpture, it’s really the gesture or the action that I’m most interested in. I prefer real figures for that reason. Just to show what they are doing rather than what sort of belt buckle they’re wearing or who does their hair. And I feel the same about their faces, so I use just enough face to get the idea across.”

Pratyeka, carving by Kelley

“You seem to choose native faces,” I remark.

“They’re archetypes. I tend to a Grecian sort of nose with no dent I the bridge. I just sort of like that. It’s not really choosing anything. It’s the sort of face that seems to have power. You could look at Greeks, Indians, a lot of brown peoples, but also, a lot of the white peoples too. There’s some sort of power in a certain mass in the jaw and the forehead and the nose—maybe Neanderthal.

“I found when I first did a carving in bone many years ago, that I could work it down from basically a Tiki into a bearded Viking, and work that down into a lightly bearded, then non-bearded Viking; into a fairly strong woman; into a delicate woman; into a baby. I was sitting there with my little tool, sculpting out on this half-inch face, going from one face to the other, and found it’s actually a convenient technique to hack your way into the material and pick a place to stop. You start out with the craggy sort of stuff just to find out where you’re going to put it all and then refine it until maybe you get back to zero again.”

We are finishing our coffee on the embankment and Kelley is feeling as if he should get back to his task. I ask him how he thinks that the state of being the generic poor-genius affects his mind and art.

“Part of it is, it keeps your feet on the ground. You can’t afford much insulation. You can’t buy your way out of problems. You are forced to see them. During the time I did Tritogenea, everything was working perfectly. I had plenty of money for what I was doing. It was just the process of having time and money at the same time. You use it. But it doesn’t seem to affect inspiration. Certainly it affects your character over the long haul.”

I ask him if he ever experiences a Pygmalion-like syndrome. If he ever bonds to his wooden people as children bond to their stuffed animals and dolls. It is something I have always wondered about sculptors of life-sized forms.

“For me, it feels more like I’m a peculiar sort of camera that can photograph what you normally can’t see. And I might bond to whoever it is I took a picture of, but the photograph is only a nice record. Naturally you don’t fall in love with that.”

The bonding, he makes clear, is with his young daughter who lives with her mother the ridge over. Kelley tends her most afternoons in his habitat-shop. She is what keeps him in Mendocino, a place that has lost much of its flavor for him, an old ‘newcomer.’

“Besides the colonial tourist, the cocaine-head Marin county-ite, there’s just the sheer population pressure, not mattering too much who it would be. Just too many people, too many dogs, too many cars, too many stereos. You can hear them all the time.”

But about his year-old daughter he says tenderly, “She suits me very well. It was love at first sight. A true joy and a pleasure. I know some other kids are pretty neat, but I wouldn’t live with them. I would live with mine. I’ve never had an unpleasant minute with her.

“My projections are all pretty standard. I live here. I won’t. I’ll continue to be able to see my daughter. I won’t. She’ll grow up great. Or she won’t. Things will work out for me or they won’t. All the juvenile fantasies pop up from time to time. All the different permutations. It’s sort of like having a TV set. Everybody’s got one in their head. After you watch it enough, you tend to ignore it most of the time.”

“How do you sum existence?” I ask him. It is hard to follow such a declaration with a lesser probe. There was a long pause. The longest between us yet. I found myself settling in for the answer, rather than perched for a talk.

When Kelley did reply, it was in a voice quiet but firm.

“Tradition is just a fad,” he said.

And we left it at that.

St. Francis, carving by Kelley, photo by S.R. Kelley

……………………………

At the Caspar Inn, at the same side table where Kelley once sent to sit in the filtered sunlight, with a beer and a bag of peanuts, to sketch out a five-panel mural that came to him in a complete set of scribble before he could sip the beer, Gary Summer describes to me an encounter that defies traditional tale.

It was while he was kayaking in the Johnston Straights between Vancouver and the mainland, seeking an orca whale.

“People think of killer whales as big and dangerous. They’re like a shark, only ten times bigger with dorsal fins that come six, seven, eight feet out of the water. Huge males.

“In an enthusiasm to know a s new species, you’re forgetful of all that. And when you’re out there alone in a kayak and you actually come across a killer whale, you are suddenly reminded that the teeth are five or six inches each and they have two sets of these very sharp teeth and they’re known for eating other mammals; that that’s how they got their name.

“A feeling comes over you, like, ‘What am I doing here?’ I was scared. For about fifteen seconds. Longer. And then that fear was gone forever and from that point on, I was only awed by its magnificent grace and beauty and this setting where they make their home.

“Killer whatels use a sonar system. Out in the water, you can actually feel the sonar beeps through the amplification of the hull of a kayak. It feels as if someone is looking right through you. And that’s precisely what they are doing. With the sonar they’re able to detect hard substance like bone. They’re seeing your insides, your skeletal insides and, in order to feel this, you have to be very quiet yourself. And very receptive. Just listenig Really hard. Then you feel it through your body. You may not hear it—though you could—the hull of the kayak, depending on its thickness, resonating to a continuous clicking.

“Likewise, any noises you make will resonate through the hull and and the whales will hear that. I think all nature can hear attitude. I think the way you approach a whale in attitude is the way a whale will approach you.

“Everything opened up to me out there. Fear (which is something that is contrived and conceived, something I remembered I should feel) disappeared when the situation became so full.

“There was no separation between the whale, the ocean, the sky, the eagles that crisscrossed overhead, the rainbows which were stuck in the sky. I felt as if this were all one. It was like a spiritual experience. And my vision of the whale became totally one of harmlessness. Like I felt harmless.

“Fear is just something we have as a result of concepts we think about. When we drop those ideas, the fear drops too. I felt as if there were no fear in the entire universe. That fear which dropped for the killer whale is the fear that dropped for death in general.

“It was an expanding experience for me. I thought the environment no longer at odds with my own being. In fact, I felt no separation from that environment. The ocean was glassy still. Sitting quiet I the kayak, I felt like a sea gull, settled on a piece of driftwood, just perfectly right where I was.”

Perhaps I should edit it a bit?

Kelley, so happy you commented. I typed the article verbatim as it appeared in the magazine. I would be happy to add any and all comments you want to make. Thanks, David