[Click on BLUE links for sources and information]

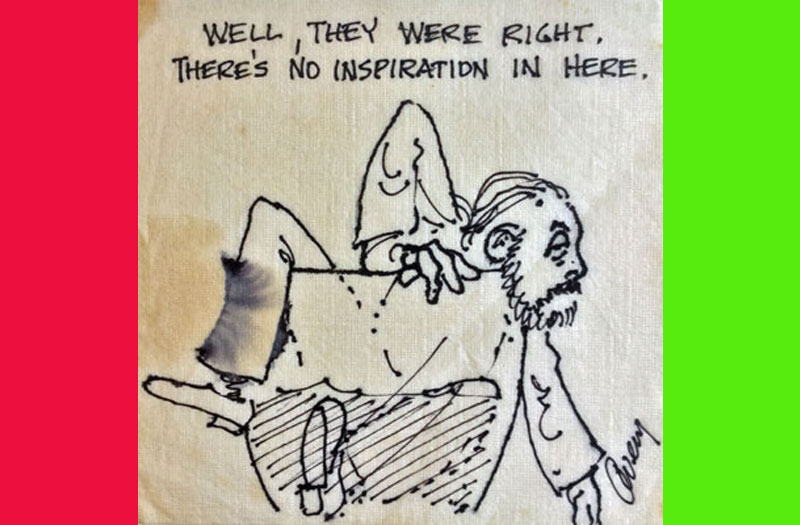

Think in the Morning does not pretend to have any special incite into the economy or the financial markets. It is true that we studied both, worked in academic and private related fields, and that we strive to stay informed but that might be, to rephrase the words of a character we fondly remember, a “determent” not a “betterment” to our understanding.

How the economy is really doing depends on the messenger and on the messenger’s bias. Trump and his supporters say things are great. Most Democrats feel otherwise. Among academic economists there is confusion.

Is the glass half full or half empty? If you are uncomfortable with either answer, maybe you’re looking at the wrong glass. Think in the Morning has this idea that the confusion might be explained by the unequal distribution of income.

Near the end of 2013 the Economist published an article claiming that out of any highly developed nation in the world the U.S. had the highest after-tax and transfer level of income inequality, with a Gini coefficient of 0.42.

Inequality is only one factor (see Eating The Seed Corn), but an important one.

After 1923, income inequality began to rise again reaching a new peak in 1928—just before the crash that would usher in the Great Depression—with the richest 1% possessing 19.6% of all income.

Today the top 1% possess about 21% of all income.

In a short persuasive Ted Talk, Richard Wilkinson provides a wealth of data to show how extreme inequality can be divisive and socially corrosive and undermine trust. The more unequal societies seem to do worse on almost all social scales. Average levels of income and growth are no longer the problem. It is relative income and social status that seems to lead to the negative impacts we see today. It’s not “the economy stupid” but “the inequality stupid”.

Wilkinson’s conclusions have not gone unchallenged. Those with great wealth and the true believers in the capitalist credo such as the Cato Institute and the Hoover Institution point out the other side of the story. And, they are not all wrong. But, as far back as Adam Smith, the so-called “father of economics” or “father of capitalism”, it was apparent that all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy:

… the true measure of a nation’s wealth is not the size of its king’s treasury or the holdings of an affluent few but rather the wages of “the laboring poor.”

As Dennis C. Rasmussen writes in The Problem of Inequality According to Adam Smith, the “father of capitalism” knew that money did not provide happiness, that too much emphasis on material things was not consistent with tranquility (the true source of happiness). Rasmussen put it like this:

“It is the vanity, not the ease, or the pleasure, which interests us.” In other words, it is the fact that people sympathize more easily with the rich that leads them to want to become rich themselves, and to (wrongly) assume that the rich must be supremely happy. “When we consider the condition of the great, in those delusive colors in which the imagination is apt to paint it, it seems to be almost the abstract idea of a perfect and happy state,” he [Adam Smith] writes.

Inequality causes the hoi polloi to envy the rich and shun the poor where the opposite might be more conducive to a cohesive society. As Rasmussen points out:

The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) and The Wealth of Nations (1776)—are full of passages lamenting the potential moral, social, and political ills of what he [Adam Smith] called “commercial society.”

Like many of his self-proclaimed followers in the 20th century, Smith did suggest that the great wealth of the few generally benefits the rest of society, at least in material terms and over the long run … More broadly, he claims that the conspicuous consumption of the rich encourages productivity and provides employment for many. So a degree of economic inequality does have its advantages, in Smith’s view.

Never the less:

What has received little attention, even by those who approach Smith’s thought from the contemporary left, is that he also identified some deep problems with economic inequality. The concerns that he voiced are, as I recently wrote in an article for the American Political Science Review, interestingly different from those that dominate contemporary discourse. When people worry about inequality today, they generally worry that it inhibits economic growth, prevents social mobility, impairs democracy, or runs afoul of some standard of fairness. These are the problems that Obama identified in his speech, and the ones that have been highlighted by academics ranging from Thomas Piketty to Joseph Stiglitz to Robert Putnam.

None of these problems, however, were Smith’s chief concern—that economic inequality distorts people’s sympathies, leading them to admire and emulate the very rich and to neglect and even scorn the poor. Smith used the term “sympathy” in a somewhat technical sense to denote the process of imaginatively projecting oneself into the situation of another person, or of putting oneself into another’s shoes. Smith’s “sympathy” is thus akin to the contemporary use of the word “empathy.” And he claimed that, due to a quirk of human nature, people generally find it easier to sympathize with joy than with sorrow, or at least with what they perceive to be joy and sorrow.

What should we do, if anything, about the unprecedented level of inequality in our society? If you think Wilkinson’s argument makes any sense, we should do something. There is no easy fix. One novel approach that might work over the long run is proposed by Guillermina Jasso in an interview by Joe Pinsker: How Individual Actions Affect Economic Inequality. We presented some other ideas in Reassessment and Reassessment II. We could repeal the Trump tax cut that was a giveaway to the rich. We could provide some meaningful assistance to those who have lost jobs do to trade instead of imposing tariffs that our own consumers pay.

Let’s get back to our original question, how’s the economy doing? Well, if you are rich, just fine. The stock market is up, real estate is up, corporate profits are up. That is where inflation is showing up, in assets, in the things rich people buy. Ordinary people have jobs but their wages are not much higher than they were a generation ago. We think the historically unprecedented inequality explains some of this. We think such high levels of inequality are dangerous.

The biggest issue that I dwell on over inequality is more of a grass roots understanding (actually an observation) that my children will not be able to achieve the level of economic stability and security that I now have after a lifetime of work. Their prospects for affordable and comprehensive health care & insurance, affordable medications, an ability to put some money into a savings account that will slowly but measurably accumulate interest (to use in case of an emergency or for a rainy day), the attainable dream of buying a home, a new car before retirement, a paid two week vacation every year after 10 years with the same employer, and the satisfaction of helping their own children advance beyond their parent’s level of education are no longer “Reasonable Expectations” for most.

The reality that the roads that were built at about the same time I began to drive are no longer smooth and adequate for the traffic on the road as the country goes deeper in debt for no reasonable improvement or even basic maintenance of public libraries, parks, museums or public schools, all the while user fees for public institutions such as the courts, universities, and government agencies are rising almost annually.

The inequality of the nation is no accident or unintended consequence of capitalism. The inherent and primary corporate aspiration to own everything in existence is really not too nuanced and complicated to for anybody to understand. Anybody who isn’t in attendance at the Great American Economy Soiree is just shit out of luck. The kids are getting tired of trying to trickle themselves up the economic ladder to the level their parents were born at.

Yes, Joshua. You aren’t alone in noticing this.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-04-07/dalio-says-capitalism-s-income-inequality-is-national-emergency

Good stuff, KD… Wealth inequality is now the number one generational issue. Those who own assets and those who don’t as the policymakers turn on monetary spigots to try and save a failing global economy. Trump will own this one. Go down worse than Hoover.