Hiatus: a pause or gap in a sequence, series, or process.

Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Silence is golden

Proverb

If the Sun & Moon should Doubt

Theyd immediately Go out

William Blake, Auguries of Innocence

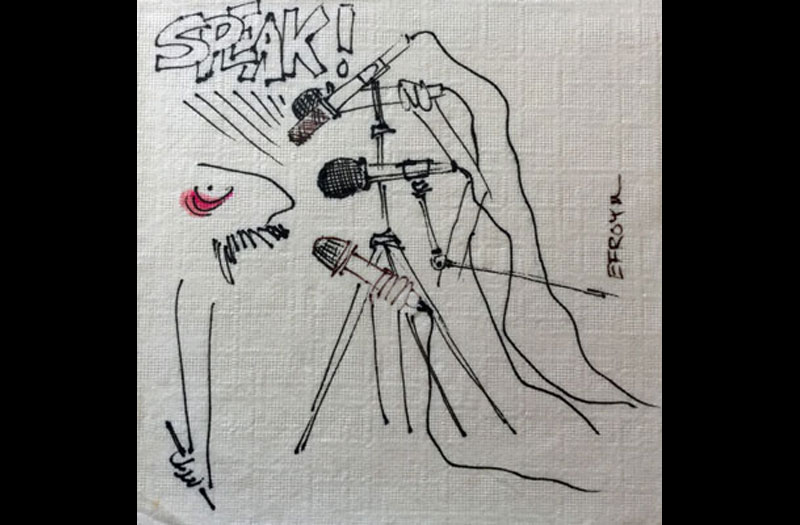

Our last blog was on February 27. Wow! Almost two months of silence. “What’s going on?” you might ask. Or, maybe you don’t care. You breathe a sigh of relief, “Thank God Think in the Morning is done. No more pretentious inane posts to slog through.” Well, we’re sorry to disappoint. We’re not done. We’ve been on hiatus.

By way of explanation, we’ve been temporarily sidelined by a momentary period of doubt. Call it writer’s block or failure of will or sloth, whatever. The fix, if one is wanted, is to follow the ubiquitous Nike slogan “Just Do It” inspired by double-murderer Gary Gilmore’s last words before being executed.

Our last posts were a first draft of a proposed story/novel, The Frolic Cafe. The plan was to write the story in real time in a series blogs. The past several weeks have been a time of reflection and judgment on how best to move forward with the novel and with the blog. The original idea was inspired by Valeria Luiselli’s second novel: The Story of My Teeth … a playful, philosophical funhouse of a read that demonstrates that not only isn’t experimental fiction dead, it needn’t be deadly, either. Luiselli’s elastic mind comfortably stretches to wrap itself around molars, Montaigne, fortune cookies and various theories of meaning. The result is an unusual “novel-essay” about art, identity and stories that delivers on the intellectual promise of her meditative, elegiac first novel, Faces in the Crowd, and her widely roving book of essays, Sidewalks, while amping up the fun factor.

Luiselli describes the process she used in writing The Story Of My Teeth as follows:

In mid-nineteenth century Cuba, the strange métier of “tobacco reader” was invented. The idea is attributed to Nicolás Azcárate, a journalist and active abolitionist, who put it into practice in a cigar factory. In order to reduce the tedium of repetitive labor, a tobacco reader would read aloud to the other workers while they made the cigars. Emile Zola and Victor Hugo were among the favorites, though lofty volumes of Spanish history were also read. The practice spread to other Latin American countries but disappeared in the twentieth century. In Cuba, however, tobacco readers are still common. Around the same time this practice emerged, the modern serial novel was also invented. In 1836, Balzac’s La Vieille Fille was published in France, and Dickens’s The Pickwick Papers was published in England. Distributed as affordable, serialized chapbooks, they reached an audience not traditionally accustomed to reading fiction.

I decided to write a novel in installments for the workers, who could then read it out loud in the factory.

I would listen to them, taking note of the workers’ comments, criticisms, and especially their informal talk after the reading and discussion. I’d then write the next installment, send it back to them, and so on.

The formula, if there was one, would be something like Dickens + MP3 ÷ Balzac + JPEG.

Many of the stories told in this book come from the workers’ personal accounts—though names, places, and details are modified. The discussions between the workers also directed the course of the narrative, pushing me to reflect upon old questions from a new perspective:

The result of these shared concerns is this collective “novel-essay” about the production of value and meaning in contemporary art and literature.

Our plan did not work out as hoped. No surprise there. We are not as talented as Valeria Luiselli.

When it is difficult to write, we find it useful to read others. A great book on writing by George Saunders: A Swim In A Pond In The Rain In Which Four Russians Give A Master Class On Writing, Reading And Life helped us determine how to proceed. The key takeaways are:

Essentially, the whole process is: intuition plus iteration.

That’s how I see revision: a chance for the writer’s intuition to assert itself over and over.

The beauty of this method is that it doesn’t really matter what you start with or how the initial idea gets generated. What makes you you, as a writer, is what you do to any old text, by way of this iterative method. This method overturns the tyranny of the first draft. Who cares if the first draft is good? It doesn’t need to be good, it just needs to be, so you can revise it. You don’t need an idea to start a story. You just need a sentence. Where does that sentence come from? Wherever. It doesn’t have to be anything special. It will become something special, over time, as you keep reacting to it. Reacting to that sentence, then changing it, hoping to divest it of some of its ordinariness or sloth, is…writing. That’s all writing is or needs to be. We’ll find our voice and ethos and distinguish ourselves from all the other writers in the world without needing to make any big overarching decisions, just by the thousands of small ones we make as we revise.

That is, the thing we would have planned would have been less. The best it could have been was exactly what we intended it to be. But a work of art has to do more than that; it has to surprise its audience, which it can do only if it has legitimately surprised its creator.

A plan is nice. With a plan, we get to stop thinking. We can just execute. But a conversation doesn’t work that way, and neither does a work of art. Having an intention and then executing it does not make good art … Artists know this. According to Donald Barthelme, “The writer is one who, embarking upon a task, does not know what to do.” Gerald Stern put it this way: “If you start out to write a poem about two dogs fucking, and you write a poem about two dogs fucking—then you wrote a poem about two dogs fucking.”

So, we gave up our plan, obviously. Our first twenty chapters are in need of revision. We refreshed our memory of the Frolic shipwreck by re-reading the three books by Thomas Layton that together embody the definitive research on that event. We paid particular attention to Layton’s description of the crew assembled for that voyage. The crew of the Frolic consisted mostly of dark-skinned lascars from Goa who spoke Portuguese.

To understand more about these people, we read a number of books about Goa. Moving forward we hope to revise and finish The Frolic Cafe offline. We will share it if and when we think it’s ready. In the meantime we expect to resume blogging on other subjects as ideas arise.

So, that’s it folks, our explanation for the hiatus and our “plan” to move forward: write, revise, repeat. Tune in as you please. We enjoy your company and comments.

Books We’ve Recently Read

The Story of My Teeth, Valeria Luiselli

Lascar, Shahida Rahman

A Swim In A Pond In The Rain In Which Four Russians Give A Master Class On Writing, Reading And Life, George Saunders

Sea of Poppies, Amitav Ghosh

Monsoon, Vimala Devi

Modern Goan Literature, Peter Nazareth

Inside/Out: New Writing From Goa

Hello Goodnight, A Life Of Goa, David Tomory

ReflectedIn Water, Jerry Pinto

Ferry Crossing, Short Stories From Goa, Manohar Shetty

Susegad: The Goan Arty of Contentment, Clyde D’Souza