[click on BLUE links for more details or information]

Trompudo

“Start with the idea that you can’t repeal the laws of economics. Even if they are inconvenient.” Lawrence Summers

My brother was eight years older, and I idolized him. When he went away to college, he had some difficulty with his writing skills and was forced to take a remedial English course fondly dubbed Bonehead English by the students. No one that I know has ever been required to take a course in Bonehead Economics. That’s unfortunate because so many people talk about the economy in barber shops, barrooms and coffee shops with little knowledge of the details.

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Sandra Lindstrom artist

Many people think they intuitively understand everything they need to know about economics because they work for a living or run a business. To read some ideas about why so many think they know as much or more about economics as the experts, look HERE.

When I studied economics, the textbook of choice was Paul Samuelson’s ECONOMICS. It was a useful text, but I wanted some historical perspective to be sure I understood the dismal science. I found an 1890 edition of Alfred Marshall’s text, Principles of Economics, and I still have that text today. People seldom consult the original texts in any field. That is a shame because there is much wisdom to be found in old books. Some people avoid the subject of economics like they avoid math and science.

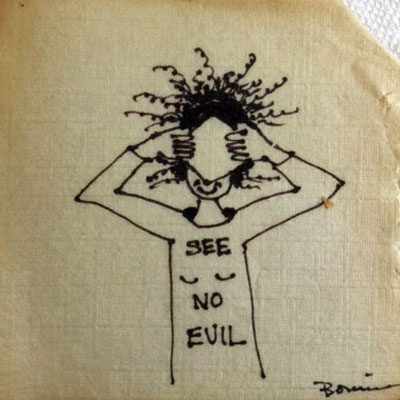

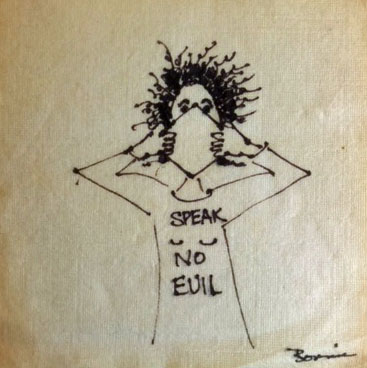

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, artist Bonnie

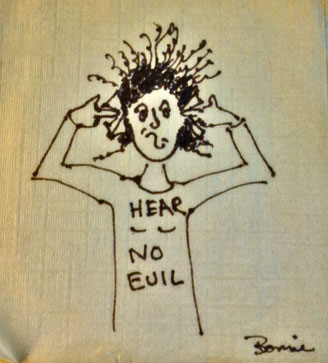

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, artist Bonnie

Others jump right in assuming they’ve got it all worked out. The very first sentence of the Marshall text is:

“Political Economy, or Economics, is the study of man’s actions in the ordinary business of life; it inquires how he gets his income and how he uses it.”

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, artist Terry

Marshall would understand how anyone who’s bought a pack of gum or tended an all-night gas station or worked as a cabbie (especially post-Uber) might think of themselves as an economic expert. They’ve had personal experience with the economy. As Professor Samuelson wrote in his text: “We each naturally tend to judge an economic event by its immediate effect upon ourselves.”

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, artist Suzanne

One of the first things I noticed when I sat down to read the Samuelson text was that he pointed out a few common fallacies in economic reasoning. It was an early example of what is now called behavioral economics. Samuelson pointed to three fallacies in particular that must be avoided in economic decision-making.

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

The “post hoc fallacy” occurs when we assume that, because one event occurred before another event, the first event caused the second event. A bonehead example would be: “Every time I wash my car, it rains. Therefore, washing my car causes the rain.” It sounds silly but much economic reasoning today fails to rise above the level of such spurious correlation.

Another error in reasoning, the fallacy of composition, occurs when it is assumed that what is true for the part is also true for the whole. For example, if one farmer increases the size of his crop, his sales and profits will probably go up. If all farmers increase their crops, a glut in supply could cause prices to fall so much that all farmers lose money. You might like the Super Bowl example better: if one fan stands up, he gets a better view; if all fans stand up at the same time, no one gets a better view. The famous economist John Maynard Keynes used the fallacy of composition to explain the difference between balancing the budget for a family and balancing the budget for the government. This is something many still do not understand including many members of Congress and the Senate.

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

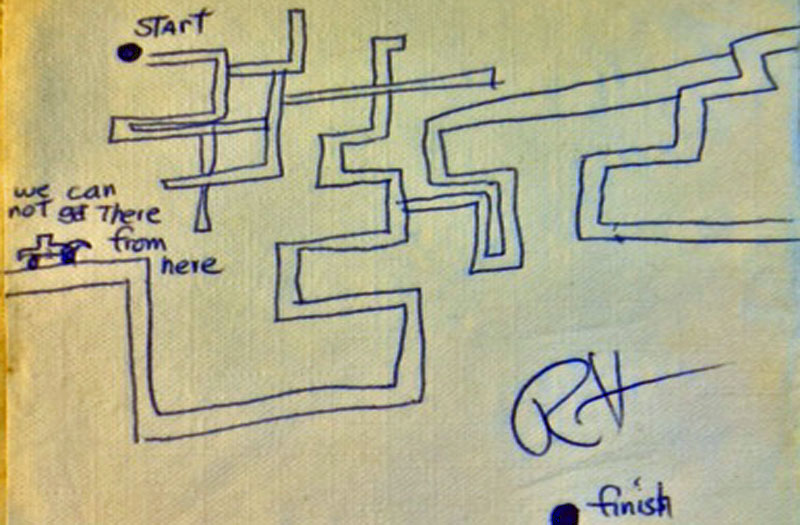

The final fallacy Samuelson discussed in his elementary text was the failure of the “other things equal” assumption when applying economic theory to economic reality. Tax policy is an area where this is important. The idea that lowering tax rates won’t lower tax receipts and might even raise them IF employment and output rise sufficiently may or may not be true depending on the “other things equal” assumption. There’s many a slip between the cup and the lip when applying economic theory to the real world, a lot of moving parts. Back of the napkin calculations and rules of thumb don’t always apply as expected.

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Bob Avery artist

There are two relationships most economists consider essential to understanding how the economy works. While the math is simple, I won’t derive the formulas here. Go to the links if you want to see why the relationships are called identities, that is, trivially true by definition.

The first relationship is based on the CIRCULAR FLOW OF INCOME and is expressed in one form as follows:

The (excess of private investment over savings) + (the government deficit) + (the trade deficit) add to zero.

That is:

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

WHERE:

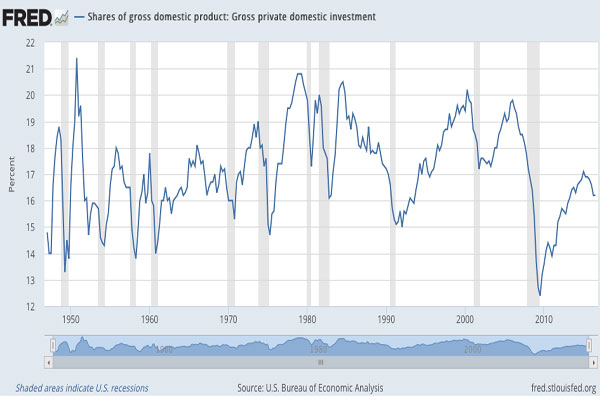

I = Investment

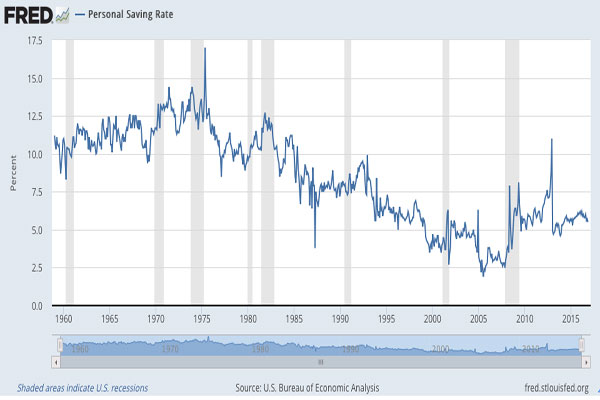

S = Private Sector Savings

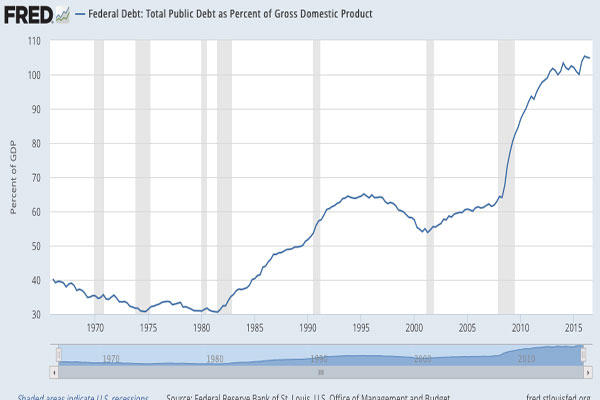

G = Government Expenditure

T = Tax Receipts

X = Exports

M = Imports

[FOR GRAPHS OF THESE ECONOMIC VARIABLES, SKIP TO THE BOTTOM]

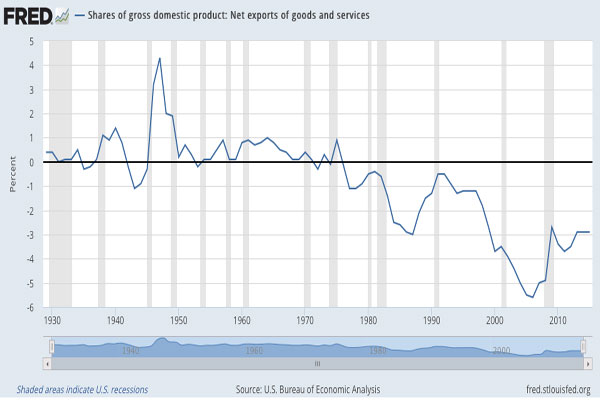

One simple conclusion (OTHER THINGS EQUAL) to be derived from this relationship is that if the government runs a budget deficit, the country will likely run a trade deficit. This will be true if Investment exceeds Savings. The “twin deficits hypothesis” is one reason why many are skeptical of President Trump’s pledge to reduce the trade deficit while at the same time lowering taxes and encouraging more investment through policies such as reducing regulations. Of course, OTHER THINGS MAY NOT BE EQUAL. President Trump’s team feels that the “animal spirits” of business owners will cause them to increase production and employment so much that government revenues and exports increase sufficiently to avoid the twin deficits problem. They may be right but most economists disagree with them.

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

The second relationship, also an identity, is usually referred to as the EQUATION OF EXCHANGE. Simply stated, the “average price level” multiplied by “real GDP” must equal the “quantity of money” multiplied by the “velocity of money.” Or,

PQ = MV

WHERE

P = average price level

Q = real GDP

M = quantity of money

V = velocity of money (i.e. rate at which a dollar turns over during a year)

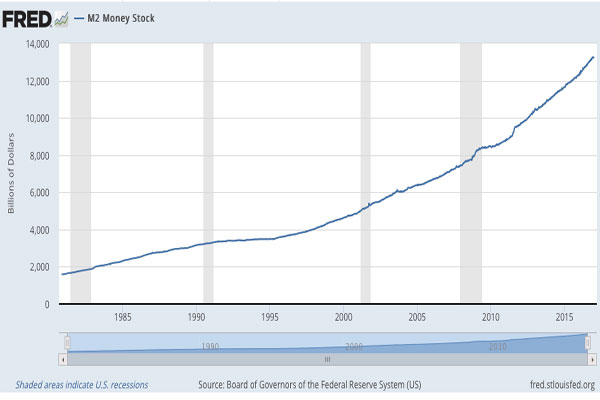

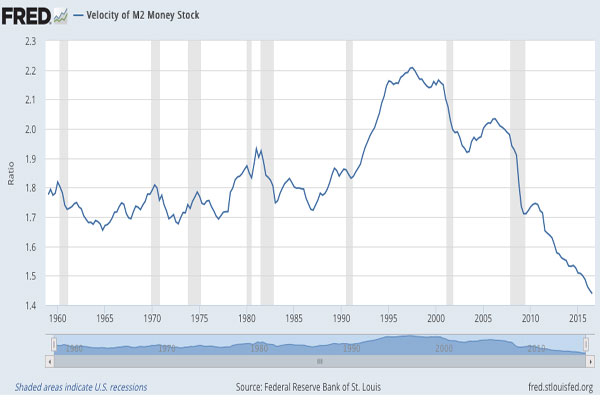

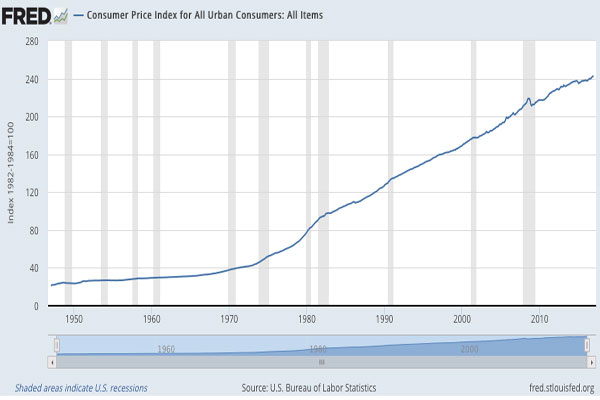

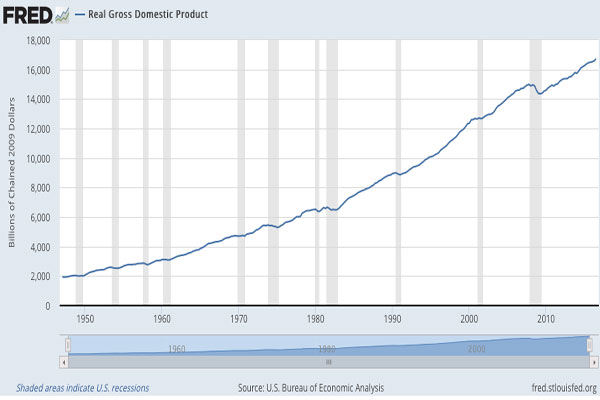

If the quantity of money is increased, as it was by the Federal Reserve Bank after the financial crisis of 2008, the formula indicates that either the price level or real output should increase. The FED was hoping to have a positive impact on real output. However, uncertainty and fear during the crisis led to a substantial decline in the velocity of money. Therefore, the impact on both the price level and output was lower and slower than expected. The money supply is now much larger. Should the velocity of money pick back up again we could see an increase in Q (real GDP). However, if the economy is now close to the full employment level as Federal Reserve Chairwoman Janet Yellen has argued recently, an increase in V could lead to an increase in P (inflation) instead of an increase in Q (output).

These relationships pose a problem for Donald Trump who is hoping to increase investment in the U.S. economy by lowering taxes and regulations. His boom could quickly be followed by inflation and a growing trade deficit.

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, artist Jack Haye

Using the CIRCULAR FLOW OF INCOME and the EQUATION OF EXCHANGE combined with an awareness of the three common fallacies in economic reasoning, it’s possible to go a long way toward understanding how the economy works. But not all the way. The key is to thoroughly understand the various components (I, S, G, T, X, M (exports), P, Q, M (quantity of money) and V). And there are many other pieces to the economy not mentioned in this short post. To thoroughly understand these concepts and all the moving parts surrounding them you must go far beyond a little BONEHEAD ECONOMICS.

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

President Truman famously asked to be sent a one-armed economist, having tired of exponents of the dismal science proclaiming “On the one hand, this” and “On the other hand, that”. Unfortunately, the only one-armed economists are those who don’t understand the complexity of what they are trying to describe.

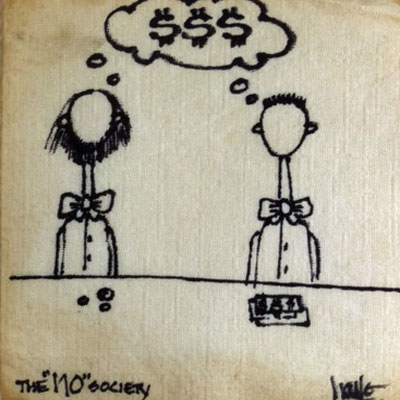

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, artist unknown

GRAPHS

So….if we are looking for a model to follow……do we follow MACHIAVELLI, ADAM SMITH, THE EMPEROR HADRIAN, SAMUELSON, TRUMP….or…our Mom’s…who usually seem smarter than all of the above?

I’d go with Samuelson, Machiavelli, and Mom in reverse order.

Is there a napkin art gallery?

Kelly House had a book of them. I will thinking of a way to gather up as many as I can then have them all together at Kelly House or Art Center. Working on it. Thanks.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0 is an accounting identity. An accounting identity is something we us ex-post to record what has happened. It is not something that carries causal information explaining what happened but rather it is something that systematically describes what needs to be explained. Using an accounting identity to infer causality might be considered to be, well, boneheaded.

Now, it is true that when budget deficits are large, trade deficits tend to be large as well. There is an indirect connection between the two. Budget deficits drive up interest rates. The higher interest rates draw in foreign capital seeking higher returns. The inflow of capital drives up the value of the dollar making US exports less competitive and foreign imports attractively priced.

You are correct that it is an accounting identity. It must hold ex post I did not mean to imply causality and I mentioned that many variable were left out in particular capital flows. My point is that the large deficits that could result from a combination of tax cuts and spending increases must be financed with a combination of increased savings or a trade deficit financed by foreign purchases of our bonds.