The artists arrived so quietly the locals could not say when Mendocino became an artists’ colony. Like a solitary ant that finds a pot of honey laying down its pheromones to attract the others, one artist discovered the beauty of the Mendocino Coast, then another, and another until like the phase change that occurs when a liquid turns into a gas the artists appeared and the locals realized without warning that their community had changed around them.

No doubt there were disturbing signs to be seen by those who looked—long hair, odd clothing, eccentric behavior, and what should have been a dead giveaway to business owners had they paid attention—an exponential rise in the demand for part-time jobs. But, no one had time to look. Like people everywhere, the locals lived ordinary lives, in an ordinary town, without any thought that things could be different.

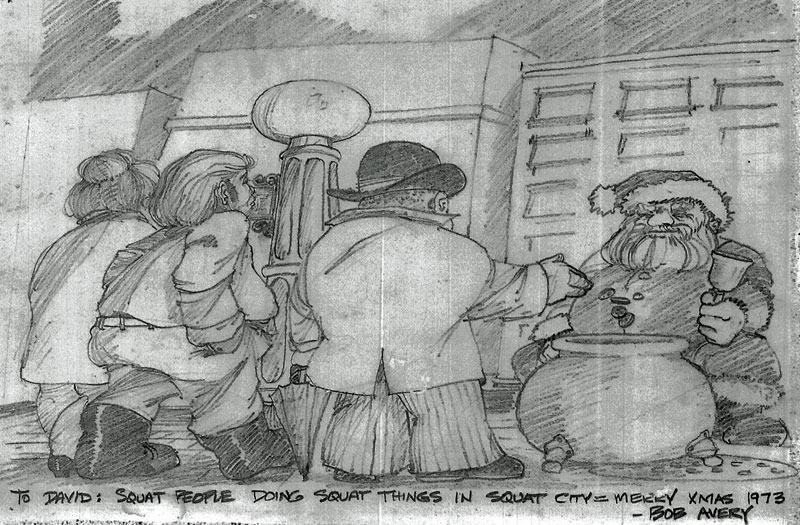

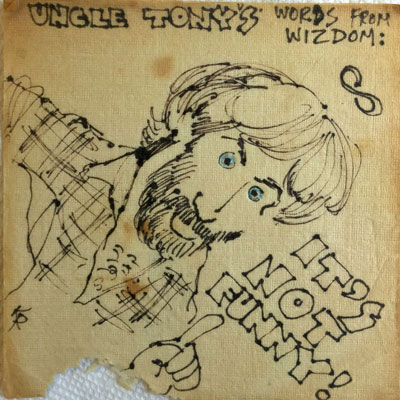

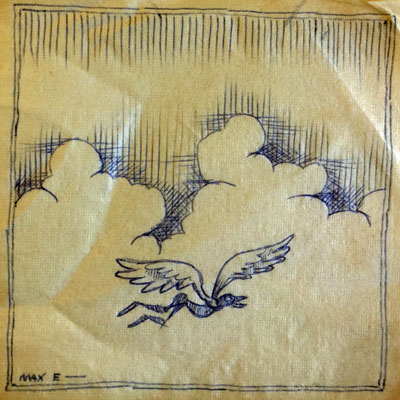

Napkin Art, Sea Gull Cellar Bar, Jack Haye artist

One day an artist came along and saw the potential and said: “I don’t know exactly why, but all my life I’ve wanted to do someplace some good.” That was the beginning, or the end depending on your point of view.

The artists, like Jonas, the Artist At Work in Albert Camus’ story, lived their happy lives. Things were going well. Art was made and sold and the town prospered. This made the businessmen happy. They were pleased the artists had come. The artists, however, began to experience the pressures of family and household. While they did sell some of their work, they found the buyers and critics alike fickle and uninformed.

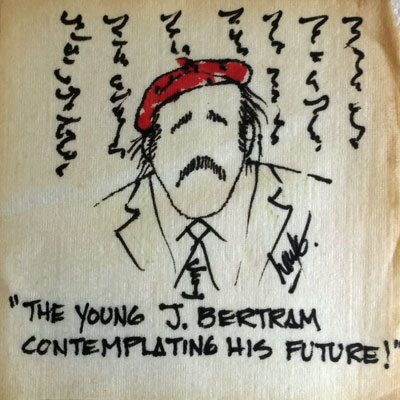

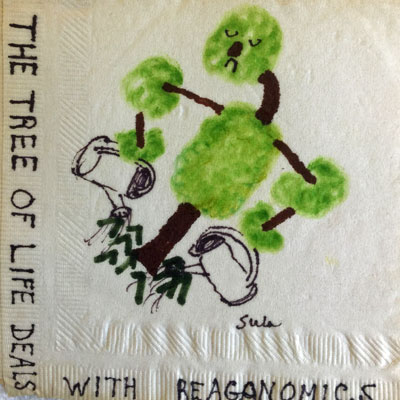

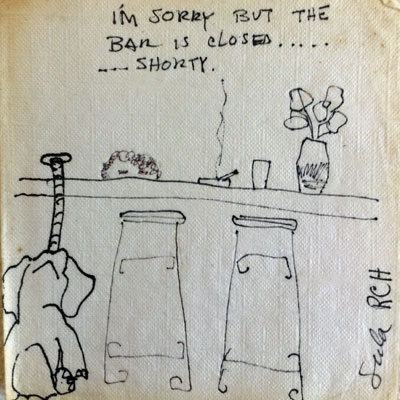

Napkin Art, Sea Gull Cellar Bar, Sula Combs artist

The worst was that the work of an artist is solitary and lonely. There is a need for something more, for solidarity with fellow journeymen, with the audience, yet one shrinks from social commitments out of jealousy, lack of time, and fear one’s work might suffer. It seems like a Hobson’s Choice, independence or interdependence.

Camus ultimately solves the problem of Jonas by choosing both in moderation. Choosing independence denies interdependence and vice versa. The artist needs both. The answer lies in finding the right balance.

In a particular time and place, the Sea Gull Cellar Bar of the 70s and 80s, the form Camus’ moderation took was in the group production of Napkin Art.

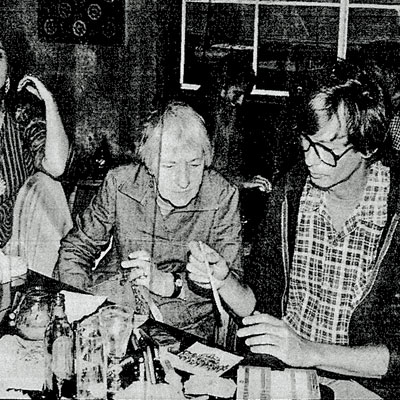

Mendocino Beacon Photo

Where the Artists Play [Mendocino Beacon November 11, 1982]

By Rob Fowler

The product of Sunday afternoons at the Sea Gull Cellar Bar will be displayed this weekend in San Francisco.

Mendocino Napkin Art, the novel form of expression which weekly draws artists together to transform paper suds-soakers into sketchpads, is being offered a corner at Gallery One, Sutter Street, in San Francisco. The reception is Friday night and is sponsored by Indelible Inc.

Napkin Art was created long ago as a catalyst to bring artists together to enjoy some lighthearted expression in an equivalent atmosphere.

Though many artists and would-be artists have dropped in over the weeks and tried their hand at creating a variety of scenes, the show will contain the best works from the 11 or so artists who form the nucleus of the group.

Included in the show are: James Maxwell, Estelle Grunewald, Jack Haye, Max Efroym, Bob Avery, Karin Kesler, Sula Combs, Roy Hoggard, Michael Fisher, Sandra Lindstrom and Mark Eanes.

Napkin Art, Sea Gull Cellar Bar, Kay Rudin artist

Napkin Art, Sea Gull Cellar Bar, Mark Eanes

A portion of the show’s proceeds will go to benefit the Josephine Randall Fr. Museum, a fitting entrance to expanded exhibits for the art form, as napkin shows first attained notoriety as fundraisers for local persons in need of medical attention.

To be shown this weekend is an assortment representing the sort of energy produced when some of Mendocino’s most talented artists pass the afternoon together.

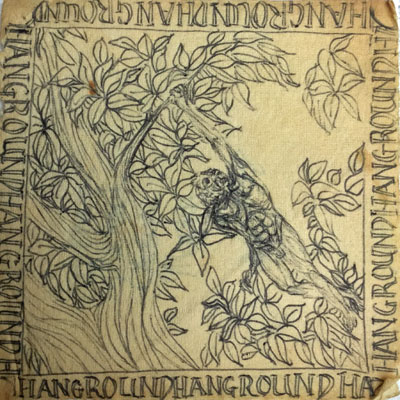

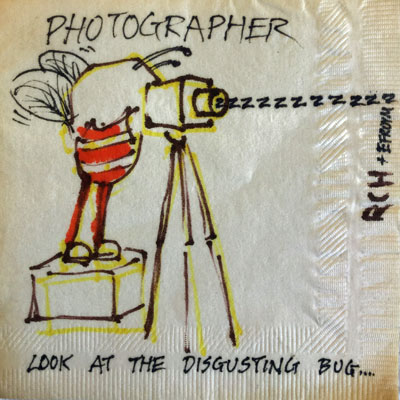

Napkin Art, Sea Gull Cellar Bar, artist unknown

From capturing a rose on a napkin to creating an “all thumbs” person—consisting of 53 thumbs—or a “Thumbhenge”—modeled after Britain’s Stonehenge—all forms of beauty and foolery are conjured onto delicate paper.

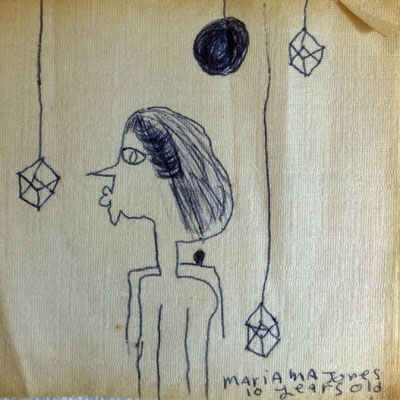

Napkin Art, Sea Gull Cellar Bar, Mariana Jones artist, 10 years old

Discussing artwork was a goal which spring boarded the continually attended sessions, but all artists agree it is their playground.

The thumb sketches point to one aspect of the playfulness which reins in the napkin sessions—that of theme work which produces stacks of usually sarcastic tro cute works on teddy bears, bunnies, udders, sperm, kittens and whatever one person starts to which others catch on.

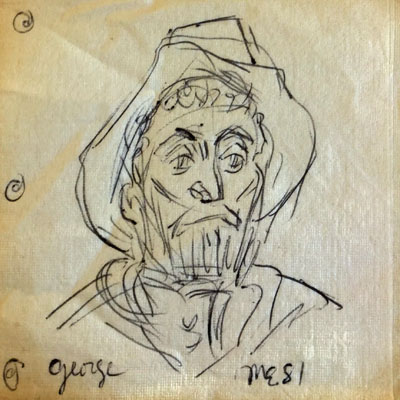

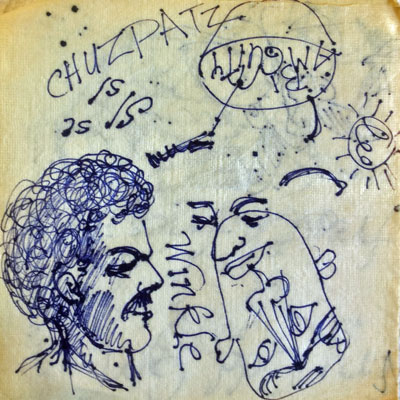

Napkin Art, Sea Gull Cellar Bar, Max Efroym artist

Has the sudden introduction of city attention changed napkin art?

“In a sense it may have,” said Maxwell, one of the founders, “but the atmosphere of being together didn’t change. When we did the first show to benefit Jim Noyes and Becky Dodds, (napkins sold for $1 for their medical aid) we began to strive for better products.

“The point is we must never lose the freshness of just getting together and enjoying this.”

“We are no longer as concerned with keeping it in the vein of cartoons. Collages, plaster napkins, sewing into the napkins and doing sketches on fabrics to form a quit have now been introduced.”

Napkin Art, Sea Gull Cellar Bar, artist unknown

“But, the interaction is still there,” he clarified.

“This is here for fun,” said Estelle Grunewald. “The primary reason is fraternizing. Mendocino is called an ‘artists’ colony, but so many of us don’t know each other. Through such things as napkin art gatherings it’s becoming a colony.”

She described the sessions as light hearted, and a short inspection of last Sunday’s gathering verified the report.

Napkin Art, Sea Gull Cellar Bar, Jack Haye

Seated in the Gull’s dimly lit lounge to the backdrop of a storm approaching from the ocean, several artists formed a human collage of dedicated detailing and playful visual conversation on napkins.

“There is no reason to feel shy here. When Matt Roland first introduced me to the group I felt very self-conscious,” said Grunewald, an artist whose work hangs in private and corporate collections throughout the Bay Area.

“But that quickly went away,” she continued. “Choosing a theme is a wonderfully democratic thing at the table.”

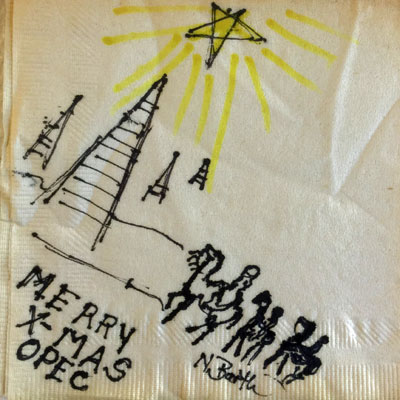

Napkin Art, Sea Gull Cellar Bar, Nancy Barth artist

Sue Moore, joining the group at this session, carefully completes a colorful dragon while Maxwell drops everything to facilitate an easy time for the interviewer.

After Efroym instigates a brief discussion about life at the Mendocino Beacon, he produces a portrait of a seemingly crazy, naked man losing control of himself beneath a “WORDS” sign.

Napkins are supplied by David Jones’ Sea Gull bartenders, to whom the group gives much praise.

Napkin Art, Sea Gull Cellar Bar, Sula Combs and Roy Hoggard artists

During the day one artist may design one-half of a portrait and leave it to be finished by another and pass-around napkins ware often circulated allowing originally conceived ideas to trans mutate at the will of the receiver.

A day’s play collects an average of 35 or so napkins which are placed on the performing stage in the lounge for bar customer perusal.

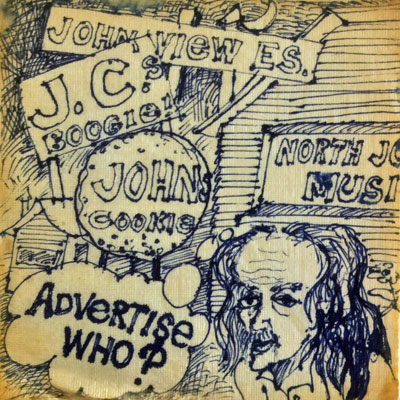

Napkin Art, Sea Gull Cellar Bar, John Chamberlin artist

Later, napkin wrapping potlucks are held where the works are placed on cardboard backing and wrapped with simple plastic cellophane for presentation.

In explaining the drive to remain simple, Estelle noted the groups indifference to an outside request to secure the works in something more permanent than plastic wrap.

“The point is we must never lose the freshness of just getting together and enjoying this,” she said.