[Click on BLUE links for sources and information]

Folks who read at least 30 minutes a week are 20 percent more likely to report greater life satisfaction and 11 percent more likely to feel creative. They’re also 28 percent less likely to suffer from depression and 18 percent more likely to report high self-esteem. Even if your worries are just garden variety, reading will probably help. Reading a book was ranked as a more effective cure for anxiety than taking a walk or chatting with a friend, and almost one in five respondents (19 percent) said reading helps them feel less lonely. Jessica Stillman, Reading 30 Minutes A Week Can Make You Healthier And Happier

Do people still read books in the era of Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram? Yes, and ironically, Millennials, the age group that dominates social media to the chagrin of their parents, are possibly among the most prolific readers of all. That’s good because reading, according to the research, can make you healthier and happier. (It can also make you wealthier according to Warren Buffett and Bill Gates.)

The percentage of adults who have read a book in the last 12 months is essentially unchanged from 2015, moving from 72 percent to 73 percent. The peak for the years Pew has surveyed is 2011, at 79 percent, but I will bet you dollars to doughnuts that something called “Fifty Shades of Grey” (released in 2011) has a lot to do with that number.

Is what you read important or is it just a matter of taste, something that we would expect to vary between people of different ethnic groups, sexes, ages, cultures and so on? It’s a fact that “literary” reading has been on the decline for several years but over 40% of Americans still read at least one novel per year. And, what you read does matter according to several recent studies.

A number of recent studies have demonstrated that fiction — particularly literary fiction — seems to boost the quality of empathy in the people who read it, their ability to see the world from another person’s eyes. And good works of literature, particularly novels, can grant you direct access to another person’s mind — whether it be the mind of the author, or of one of their imagined characters — in a way that few other works of art can.

Young girls reading at a bakery in Oaxaca, Mexico

Can we attribute populism, tribalism, and other divisive social and political trends to the fact that we are reading fewer literary works? Maybe, but a lack of reading is probably not the only or even the most important factor involved. Demographics, religion, jobs, inequality all play a role. But, if reading more of the “right” stuff can help make society more cohesive, it’s worth encouraging.

The percentage of reading done as e-books has been steady since 2014, at around 28 percent. I’m guessing that figure is much lower than Amazon would wish for, and may even help explain why it is starting to open retail stores. Amazon is probably also concerned that 40 percent of readers consider themselves print exclusive, while 6 percent read only digital books.

Are people who read more “smarter” than people that don’t? Those who are defensive about not reading like to point to the “bumbling professor” who walks out of his house in the morning lost in thought and forgets to change from his pajamas into his day clothes or the “math genius” that can’t tie his shoes. In other words, common sense is not something you can learn from a book. But, preliminary evidence does indicate that reading can raise one’s IQ. So, it probably doesn’t hurt to build a little reading into your busy schedule if you haven’t done so already.

Children’s Library along Alcala Street in Oaxaca, Mexico

Who doesn’t read? According to Pew Research 24% of Americans have not read a book in the past 12 months. The largest subgroups of nonreaders include Hispanics, people with no more than a high school education, low-income, and those who live in rural areas. People who read the most include the college educated, middle to high income, and surprisingly, those under 50 (although a third of teenagers don’t read books for pleasure anymore). Millennials read more than other age groups but they also read differently. They read for information, are good scanners, are visually oriented and they are Internet oriented.

You might be inclined to read a bit more if you have some very specific questions you think a good book could answer. For example: what books can help me deal with depression and anxiety, or what can I read to tackle a midlife crisis, or which modern novelists could rekindle my love of fiction and so on. The British newspaper The Guardian has a useful site where you can find some of the answers: Book Clinic. The questions (your questions since you can ask them) are answered by experts in their field. It’s a good place to start to find a book you might be interested in reading.

The difficulty of finding a good book

At Think in the Morning we love to read as you may have surmised if you read JP’s Books. We understand that our readers and friends may not be as enthusiastic about books as we are. It occurred to us that you may enjoy a list of books that can be read a little bit at a time, a page or so with an entire thought that can be absorbed in a few minutes. Our list is not at all complete, but it gives some examples of books we like that can be read in spurts whenever you happen to have a few minutes free. Our list follows with a few comments mixed in. Enjoy.

I particularly like Michael Pollan’s Food Rules: An Eater’s Manual. Diet books are boring and anyone who has tried to diet knows that most diet books are a scam and the diets don’t work at least not in the long run. Pollan’s book isn’t easy to follow but his sixty-four rules are sensible, enjoyable to read, and well documented. I hope to be able to follow his advice someday. The overriding rule: Eat Food, not Too Much, Mostly Vegetables, pretty much says it all. I like Rule 7: Avoid food products containing ingredients that a third-grader cannot pronounce. And, even more, Rule 11: Avoid foods you see advertised on television.

We are all interested in what happens after we die. David Eagleman uses his prolific imagination to provide us with forty alternatives in Sum: Forty Tales From The Afterlives. The tales run 3 or 4 pages. Each is a different afterlife as envisioned by Eagleman. Here is one afterlife he calls Perpetuity:

If you wake up and find yourself in this suburb, you’ll know you were a sinner. Not that the accommodations aren’t nice; there are televisions here with many stations to choose from. You have neighbors on all sides of you, with whom you interact occasionally. There are shelves brimming with books that tell good but implausible adventure stories. The children here are sent to school, and the adults go to work. Careers are easy and the groceries are cheap. You learn that this is called Heaven. We live close to God here. The only mysterious part is that all the good people you knew—the Samaritans, the saints, the generous, the altruists, the selfless, the philanthropists—are not here. You inquire whether they have been sent on to a better place, a super-Heaven, but discover that these good people are rotting in coffins, the foodstuff of maggots. Only sinners enjoy life after death. There have been many theories about why God would arrange things this way. Everyone has a hypothesis, and it’s the customary topic of discussion at barbecue cookouts. Why are we the ones rewarded with an afterlife? It seems clear that God doesn’t much like the inhabitants here; He rarely visits us. But He wants to make sure He keeps us alive. The woman at the coffee shop insists He is keeping the bad ones around like the Romans kept gladiators: at some point we will fight to the death for His amusement. Your neighbor across the street theorizes that we are being stockpiled to wage war against another God in a neighboring universe, and only the sinful make useful soldiers. But they’re both wrong. In truth, God lives a life very much like ours—we were created not only in His image but in His social situation as well. God spends most of His time in pursuit of happiness. He reads books, strives for self-improvement, seeks activities to stave off boredom, tries to keep in touch with fading friendships, wonders if there’s something else He should be doing with His time. Over the millennia, God has grown bitter. Nothing continues to satisfy. Time drowns Him. He envies man his brief twinkling of a life, and those He dislikes are condemned to suffer immortality with Him.

Library behind the National Palace in the Zocalo in Mexico City

Wislawa Szymborska may not be a household name in America but she is a hero in Poland. Szymborska is a Polish poet and writer who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1996. Think in the Morning highly recommends her poems. Nonrequired Reading is an eclectic set of “sketches” per her own introduction to the book (see below). Most of the sketches are just a few pages and easy to read in a couple of minutes while you are waiting at the doctor’s office or to pick up your kids from school.

I GOT THE IDEA OF writing Nonrequired Reading from the section called “Books Received” you find in many literary journals. It was easy to see that only a tiny percentage of the books listed later made their way to the reviewer’s desk. Belles lettres and the most recent political commentary always received privileged treatment. Memoirs and reprints of the classics stood some chance of being reviewed. The odds for monographs, anthologies, and lexicons were much slimmer, though, and popular science and how-to books were virtually guaranteed to go unnoticed. But things looked different in the bookstores. Most (if not all) of the rapturously reviewed books lay gathering dust on the shelves for months before being sent off to be pulped, whereas all the many others, unappreciated, undiscussed, unrecommended, were selling out on the spot. I felt the need to give them a little attention. At first I thought I’d be writing real reviews, that is, in each case I’d describe the nature of the book at hand, place it in some larger context, then give the reader to understand that it was better than some and worse than others. But I soon realized that I couldn’t write reviews and didn’t even want to. That basically I am and wish to remain a reader, an amateur, and a fan, unburdened by the weight of ceaseless evaluation. Sometimes the book itself is my main subject; at other times it’s just a pretext for spinning out various loose associations. Anyone who calls these pieces sketches will be correct. Anyone insisting on “reviews” will incur my displeasure. One more comment from the heart: I’m old-fashioned and think that reading books is the most glorious pastime that humankind has yet devised. Homo Ludens dances, sings, produces meaningful gestures, strikes poses, dresses up, revels, and performs elaborate rituals. I don’t wish to diminish the significance of these distractions—without them human life would pass in unimaginable monotony and, possibly, dispersion and defeat. But these are group activities, above which drifts a more or less perceptible whiff of collective gymnastics. Homo Ludens with a book is free. At least as free as he’s capable of being. He himself makes up the rules of the game, which are subject only to his own curiosity. He’s permitted to read intelligent books, from which he will benefit, as well as stupid ones, from which he may also learn something. He can stop before finishing one book, if he wishes, while starting another at the end and working his way back to the beginning. He may laugh in the wrong places or stop short at words that he’ll keep for a lifetime. And, finally, he’s free—and no other hobby can promise this—to eavesdrop on Montaigne’s arguments or take a quick dip in the Mesozoic.

Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez gave a Spanish-language copy of Eduardo Galeano’s book Open Veins of Latin America to U.S. President Barack Obama when Obama made his first diplomatic visit to the area for the Fifth Summit of the Americas. That alone might encourage some of you to read Galeano, or not. Galeano is worth reading whatever your political affiliation. His book Mirror, Stories of Almost Everyone consists of a few hundred short pieces each digestible in a short single gulp. Here is his Brief History of Civilization.

And we tired of wandering through the forest and along the banks of rivers. And we began settling. We invented villages and community life, turned bone into needle and thorn into spike. Tools elongated our hands, and the handle multiplied the strength of the ax, the hoe, and the knife. We grew rice, barley, wheat, and corn, we put sheep and goats into corrals, we learned to store grain to keep from starving in bad times. And in the fields of our labor we worshipped goddesses of fertility, women of vast hips and generous breasts. But with the passage of time they were displaced by the harsh gods of war. And we sang hymns of praise to the glory of kings, warrior chiefs, and high priests. We discovered the words “yours” and “mine,” land became owned, and women became the property of men and fathers the owners of children. Left far behind were the times when we drifted without home or destination. The results of civilization were surprising: our lives became more secure but less free, and we worked a lot harder.

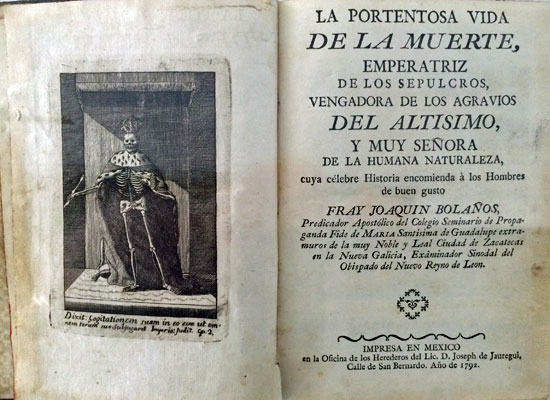

Book on display, Uabjo Biblioteca Francisco Burgoa library in Museo de las Culturas de Oaxaca, Oaxaca, Mexico

The Tao te Ching needs no introduction. In its current form it consists of 81 chapters none of them much more than one page. You could keep a copy in your back pocket to read at random when you have a few unexpected minutes. Or, you could keep a beautifully bound and illustrated copy on your coffee table to impress friends. I have given several away at wakes for friends, sadly an all too common occurrence these days.

Mason Currey’s wonderful book Daily Rituals: How Artists Work gave dozens of useful answers to a question that nagged me for years and still does—how do creative people get things done? Here is the chapter on Toulouse-Lautrec.

Toulouse-Lautrec did his best creative work at night, sketching at cabarets or setting up his easel in brothels. The resulting depictions of fin de siècle Parisian nightlife made his name, but the cabaret lifestyle proved disastrous to his health: Toulouse-Lautrec drank constantly and slept little. After a long night of drawing and binge-drinking, he would often wake early to print lithographs, then head to a café for lunch and several glasses of wine. Returning to his studio, he would take a nap to sleep off the wine, then paint until the late afternoon, when it was time for aperitifs. If there were visitors, Toulouse-Lautrec would proudly mix up a few rounds of his infamous cocktails; the artist was smitten with American mixed drinks, which were still a novelty in France at the time, and he liked to invent his own concoctions—assembled not for complementary flavors but for their vivid colors and extreme potency. (One of his inventions was the Maiden Blush, a combination of absinthe, mandarin, bitters, red wine, and champagne. He wanted the sensation, he said, of “a peacock’s tail in the mouth.”) Dinner, more wine, and another night of boozy revelry soon followed. “I expect to burn myself out by the time I’m forty,” Toulouse-Lautrec told an acquaintance. In reality, he only made it to thirty-six.

Anyone with children or grandchildren knows how naturally inquisitive they are, always asking questions. Big Questions From Little People: And Simple Answers From Great Minds by Gemma Elwin Harris is an absolute delight and easy to read I short spurts. Here is a little taste.

Question: Is It OK To Eat A Worm? Answer: Bear Grylls, explorer & survival expert

Well, here’s the thing … If your life depends on it, then you bet it is OK to eat a worm. But you don’t want to be doing it every day, trust me. And if you do eat one, you’ve got to be careful because worms can have some bad stuff in their tums (as they wiggle around all day

underground!) So it’s best to cook them up. I find if you boil them up with some pine needles over a fire, it makes them taste a little bit better. I will never forget the first worm I ate. I was standing there, incredulous, watching this soldier suck a long, juicy worm up between his teeth and munch it down raw. I was almost sick. When it was my turn, I think I nearly was sick. But guess what? If you do it enough and you are hungry enough, then it gets easier. And there is the real secret of life and survival: if your spirit is strong enough, you will find a way to do the impossible. That’s the lesson of the worm. Oh, and remember: keep smiling even when it’s raining. That’s the second-most important lesson. So get out there and explore!

The famous Russian author Leo Tolstoy is known for his long novels. If you are intimidated by War and Peace or Anna Karenina you might try A Calendar of Wisdom: Daily Thoughts to Nourish. About this little book Tolstoy says:

I hope that the readers of this book may experience the same benevolent and elevating feeling which I have experienced when I was working on its creation, and which I experience again and again, when I reread it every day.

You might want to start with the wisdom lesson on your birthdate. It’s not something you can eat like a fortune cookie but it might give you that benevolent and elevated feeling Tolstoy speaks of.

This list can and should be expanded but I’ve already gone on too long. The bottom line is simple. It’s good to read, good for you and good for society. If you find novels or long books of any sort intimidating, you can start with a great number of books that are designed to be read a little bit at a time. This might get you started on a life-long healthy habit. If you’ve read this far, you’ve got the hang of it.

Does reading Think in the Morning count?

Double