[Click on BLUE links for sources and information]

Lesley Stahl: Have you seen the really bad schools? Maybe try to figure out what they’re doing?

Betsy DeVos: I have not– I have not– I have not intentionally visited schools that are underperforming.

Lesley Stahl: Maybe you should.

Betsy DeVos: Maybe I should. Yes.

CBS News, 60 Minutes Interview

The advice Lesley Stahl gave Betsy DeVos, to visit and study before you judge, is good advice. Travel is one way to understand other cultures and people. In recent posts we’ve been exploring whether or not travel encourages world peace. You can find our past travel posts HERE, HERE, and HERE. In this final post we will focus on Russia.

The first point to be made is that Russia is not Putin any more than America is Trump. American views of Russia are all over the map. Love it, hate it, fear it, fascinated by it, totally ignorant of it. Most of us have listened to Prokofief’s Peter and the Wolf, watched the Nutcracker Ballet by Tchaikovsky, played with those curious matryoshka dolls, maybe read Tolstoy or Dostoevsky or watched Doctor Zhivago based on the novel by Boris Pasternak. But this only scratches the surface. Russians are a very diverse people, just like Americans.

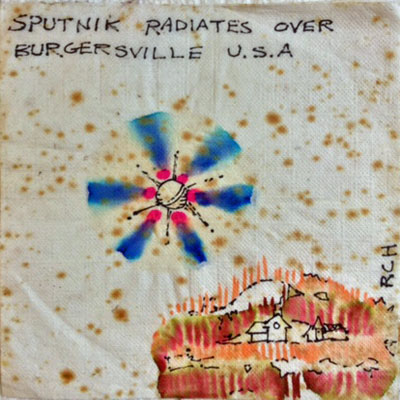

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

Maxim Gorky’s Reply To A Questionnaire From An American Magazine (1927-29)

from The City of the Yellow Devil by Maxim Gorky

Does your country hate America, and what do you think of America’s civilization?

I am not authorized to reply on behalf of the 150 million citizens of my country, for I have no way of asking them what they think of your country.

I imagine that even in the countries whose blood your capitalists are coining into dollars—in the Philippines, in the South American republics, in China—and even among the ten million coloured people in the USA, one would not find a single intelligent person who would presume to tell you on behalf of his people: “Yes, my country, my people hate America, hate all her people, the workers as well as the billionaires, coloured as well as white; hate the women and children, the fields, rivers, forests, beasts and birds, the past and present of your country, its science and scientists, its magnificent technology, Edison and Luther Burbank, Edgar Poe, Walt Whitman, Washington and Lincoln, Theodore Dreiser and Eugene O’Neill, Sherwood Anderson, all its gifted artists, and the splendid romantic Bret Harte, the spirituial father of Jack London—Thoreau, Emerson, and everything that makes up the United States or America and all who lie in these states.

I hope you do not expect to find anyone idiotic enough to give such an answer to your question, an answer filled with such hatred for people and culture.

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, author unknown

In spite of Gorky’s warning, I’ll venture a generalization about the Russian people: they enjoy American music and culture. Iggy Pop performed in Moscow last year (at age 70). As an aside, let me mention that the famous traveler and food writer Anthony Bourdain once interviewed Iggy Pop. While the interview has nothing to do with Russia, I include it here to, in a way, set a tone for what is to follow.

Many, many American artists, musicians, and authors have visited Russia over the years. David Bowie traveled to Russia three times and gave a performance there in 1996. Michael Jackson wrote Stranger in Moscow when he visited the city on his Dangerous tour. Billy Joel wrote the song Leningrad while touring Russia in 1987. (See To Russia with Love: 6 American Songs about the world’s Biggest Country)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=108&v=pEEMi2j6lYE

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=12&v=LgD_-dRZPgs

Befriending the Russian people does not mean befriending the Russian dictator, Vladimir Putin. The same is true of many countries governed by authoritarian leaders including North Korea, the Phillipines, Turkey, etc. Kieth Gessen is a Russian-born American novelist, journalist and translator who in his new novel, A Terrible Country, gives his view of what it’s like living in Russia today. [FYI: according to recent statistics there are about 3 million Russian-Americans living in the United States today of which about 1 million were born in countries formerly part of the USSR.]

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

This was not the Russia I remembered. I found several European-style cafés, with small tables and little signs in the window that said WI-FI. But they were incredibly expensive. The cheapest item on the menu, a tea, was two hundred rubles—almost nine dollars …

The country had become rich. Not everyone was rich—my grandmother wasn’t rich, and in fact, speaking of robbery, she had been robbed of certain things—but overall, generally speaking, a lot of people, especially in Moscow, were pretty well off …

Everyone in Moscow seemed to drive a black Audi and there were websites where you could order a prostitute after reading all her customer reviews. Outside of a few stinky Soviet-era groceries, food was expensive, rent was outrageous, and hockey games were closed to outsiders. Every time I walked into the Coffee Grind and bought the cheapest item on the menu, I was amazed at all the other customers …

So this was the Putinist bargain: you give up your freedoms, I make you rich. Not everyone was rich, but enough people were making do that the system held. And who was I to tell them they were wrong? If they liked their Putin, they could have him … Kieth Gessen, A Terrible Country

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, James Maxwell artist

The “gentrification” of Russia starting in the 1990s was one factor leading to an increasing anti-Americanism. The Russian writer and literary critic, Andrei Sinyavsky (pen name Abram Tertz, author of Fantastic Tales) wrote about this in The Russian Intelligensia (1997):

Anti-Americanism has grown. This has been caused by the glaring abundance of foreign goods, which only rich people can afford, and by the fact that Moscow is now blanketed by foreign advertising, signs, and names that irritate me, even thought I have been living in France for a long time and have no negative feelings whatever toward America. But it is irritating that Moscow sports an enormous neon sign advertising The Very Best American Tobacco, that this tobacco is unaffordable, and that your income is barely enough for a lousy domestic Belomor. It looks like foreign occupation. Cities are studded with signs such as Casino or Casanova Night Club (Great Intimate Atmosphere); a restaurant called At the Banker’s; The Lolita Venereal Disease Clinic; the Flamingo Bar; and the Gallant grocery store. Just try to imagine such signs not in Moscow—which has anything and everything—but in the small, ancient town of Pereslavl-Zalessky, which has the Eden dry cleaners, but no sidewalks. Against the background of dirt and poverty foreign words sound like a nasty parody of Western lifestyles. (The Russian Intelligensia, p.14)

and

… Gorbachev admitted in his book Perestroika: “We missed a lot of opportunities for small business for the agrarian sector, and for reform of the price-formation system. We couldn’t regulate the market. That led to increasing dissatisfaction because the reforms did not produce tangible results.”

It is true [Sinyavsky continues] that the freedom granted in the political sphere was not paralleled by successes in the economic sphere. Even minimal success in this area would have been highly advantageous for Gorbachev by broadening the social base of perestroika. As far as the economy was concerned, Gorbachev simply acted too late. Perhaps the solution to economic problems was more complex, requiring more time and lengthy, intensive efforts. During that early period of hope and joyful expectation the majority of the population supported perestroika, but the people quickly cooled to it. They had gotten freedom but not bread. As a result Gorbachev and Yeltsin symbolized the same kind of negative force—that of ruin. (p. 29 The Russian Intelligensia)

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Akamu Pali artist

In a recent review by Isaac Chotiner of SLATE, Gessen talks in detail about what Americans don’t understand about Russia directly. A few quotes will demonstrate the major points he makes:

I had certain perspective on what was going on over there. Roughly speaking, that there was a lot of continuity between Yeltsin and Putin, that the ’90s were really bad, and really traumatic in a way that I think most American descriptions of Russia don’t really believe, don’t really take into account. I think Putinism is a response to that trauma. I don’t think it’s the right response, but it’s a response. You know, I was kind of trying to write this in my articles, and I didn’t feel like I was convincing a lot of people.

What do you make of the conversation about American–Russia relations right now?

I mean, obviously I find it horrifying. You know, you already had a really bad kind of feeling about Russia and a really bad conversation around Russia at the end of the Obama administration. In a way, the breaking point is really Ukraine, rather than Trump, at least kind from where I’m sitting and looking at it. That’s when you had a lot of the media, certainly a lot of policymakers, basically saying we did everything we could. We bent over backward for 25 years, for the Russians, and this is what we got.

My feeling, or the Russian perspective on that, and I don’t mean Putin’s personal perspective but, like, the reasonable Russian perspective is that the United States has just kind of dictated terms to us for 25 years. It did not feel to us at all like you were bending over backward. You were telling us what to do. If we play along with it, then you were very happy to treat us as a junior partner, and whenever we had a problem with whatever you were doing, you ignored us. Including, for example, the invasion of Iraq. So, after Ukraine, I feel like in the U.S. it was just a lot of blaming Putin personally for all this. Basically suggesting that anyone but Putin would have behaved in a different manner, whereas my argument would be that most Russian leaders who would have emerged from the ’90s would have behaved in a pretty similar manner.

I don’t disagree, but you can always point to past reasons why people behave the way they do. Saddam Hussein tried to kill an American president and invaded his neighbors. It doesn’t make people’s complaints about the invasion of Iraq less valid. Even if Russia was mistreated by the United States, I’m not sure how far that gets us when thinking about how to deal with Russia in 2018, other than in the long run you try to change American foreign policy.

I feel like there’s this tendency, probably a tendency everywhere, but certainly in the U.S. to say: OK, all this history is well and good, but what do we do now? We have this crisis. Muammar Qaddafi is about to slaughter the opposition. What do we do, right? Slobodan Milosevic is sending troops into Kosovo. What do we do now? What do you want me to do tonight? As a person who’s not in government, right, I don’t want to play that game. There’s never a good answer for it. Once you’re in the crisis, I’m not your crisis manager. To me, the history does matter. As long as we can treat everything as one crisis after another, and as soon as we’re through the crisis, we sort of breath a sigh of relief and move on to something else, we don’t think of the damage that we’ve done.

When given the chance, people often find more in common with each other when they take the time to communicate, to travel, to visit, when they try to understand different points of view–that is, when they warm to the simple idea “Maybe I should, yes.” There is no guarantee that it will always work, but it’s worth a try.

Early Russian visitors to the United States were both impressed and appalled by what they saw. The criticism was often based on a perceived lack of appreciation for higher culture, and on what they witnessed as gross materialism, racism, and inequality.

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin, Roy Hoggard artist

Like many Russian visitors, Vladimir Mayakovsky had love-hate relationship with New York.

The way by which you got your millions is of no concern in America,” wrote the Soviet poet Vladimir Mayakovsky during a trip to New York City in 1925. “Everything is ‘business;’ and business matters are everything that makes a dollar.” Mayakovksy came by sea, “crawling for eighteen days, like a fly over a mirror.” Mayakovsky showed his readers “America just before the Great Depression, a country full of promise but also locked in fierce moral debate about wealth, alcohol, race, and much more.

All around there are well-kept roads crawling with Fords, and various structures of the technological fantasy-land.

Around the small cafés, single men start getting their body machinery into gear, cramming the first fuel of the day into their mouths — a hurried cup of rotten coffee and a baked bagel, which right here, in samples running to hundreds, the bagel-making machine is slinging into a cauldron of boiling and spitting fat.

Everyone’s lunch is dependent on the weekly wage,” he wrote of New York, delineating those who bought a snack in a paper sack from those who fed a machine a few nickels for a sandwich, from the wealthy, who dined at restaurants representing a range of international cuisines, “anywhere except tasteless American ones which guarantee you gastritis with Armour tinned meat that’s been lying around almost since the War of Independence.

He positively hated Coney Island:

I have never seen such depravity stimulating such ecstasy.

There isn’t a country that spits out as much moralistic, lofty, idealistic, sanctimonious rubbish as the United States.

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

Ilya Ilf and Evgeny Petrov toured the United States from the East coast to the west coast and back during the Great Depression (1935-6). Their observations are perceptive, humorous, and provide an interest view of that difficult time from a Russian’s point of view. Here are a few examples from their book American Road Trip.

The more people and things we saw, the less we understood America. We tried to sum things up in generalizations. Dozens of times a day we exclaimed:

- Americans are as naive as children!

- Americans are excellent workers!

- Americans are hypocrites!

- Americans are a great nation!

- Americans are cheapskates!

- Americans are generous to a fault!

- Americans are radicals!

- Americans are dull, conservative, and hopeless!

- There will never be a revolution in America!

- There will be a revolution in America in a few days!

It was a real muddle, from which we wanted to extricate ourselves as soon as possible. And, slowly, that extrication began. One after another various spheres of American life started to become clear to us …

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, artist unknown

Right away we had a little problem. We thought we would stroll slowly along, looking around attentively – studying everything, so to speak; observing, taking it all in and so on. But New York isn’t a city where people move slowly. People weren’t walking past us, they were running. So we also started to run. And we haven’t been able to stop since. We lived a whole month in New York and the entire time we were rushing somewhere as fast as we could go.

Advertising has so permeated American life that if one fine day Americans woke up and found that all advertising had disappeared, the majority of them would be in a desperate position. It would be impossible to figure out things like: Which cigarettes to smoke? Which store to buy clothes at? Which refreshing drink to quench your thirst with—Coca Cola or Ginger Ale? Which whiskey to drink—White Horse or Johnny Walker? Which company’s gasoline to buy—Shell or Standard Oil? Which God to believe in—the Baptist one or the Methodist one? In general, everything would go to hell without advertising. Life would become unbelievably complicated. People would have to think for themselves about every single thing they did.

The average American, notwithstanding his apparent energetic activity, is actually very passive by nature. You have to give everything to him pre-cooked. Tell him which drink is better, and he’ll drink it. Tell him which political party is more in his interest, and he’ll vote for it. Tell him which God is the “real” one, and he’ll believe in him. But whatever else you do, don’t force him to think. He doesn’t like to and is not very good at it.

Credit is the basis of American trade. Everything in an American’s house is bought on credit: the stove on which he cooks his meals, the furniture on which he sits, the vacuum-cleaner with which he tidies the room – everything was acquired by down payment. In point of fact neither his house, nor his furniture, nor the wonderful gizmos of mechanized everyday life belong to him.It would seem that in the life of the average American, that is, the American who has work, there would have to come a moment when he pays off all his debts and becomes a real, genuine proprietor. But it’s not that easy. His car has gotten old. The company is offering a beautiful new model. The company will take the old car for a hundred dollars, and is giving wonderful discount rates for the remaining five hundred: so many dollars the first month, and then…

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

Maxim Gorky wrote a number of letters to his friends in Russia while he was visiting America in 1906:

… everything is judged by money, everything is forgiven for money, everything is sold for money. A remarkable country, I will tell you! Everybody is obsessed with this truly morbid passion for gold, some are repulsive in their ugliness, and others are often pitiful and funny … I am working hard. I do not have it easy here, but then it’s exciting as being in hell.

D’you know what I’ll tell you? We’re far ahead of this free America for all our misfortunes. This becomes especially apparent when you compare the local farmer or workman with our peasants and workmen.

It will be a long time before there’s a revolution here, unless it comes crashing down on the dumb skulls of the local multimillionaires in about ten years from now. My, what an interesting country! You should see what these devils are doing, how they work, how full they are of energy, ignorance, smugness and barbarity! I admire them and I curse them, I feel sick and gay and damned amused! Do you want to be a socialist? Come here then. The need for socialism has been revealed with fateful clarity.

Do you want to be an anarchist? You can become one within a month, I assure you.

Actually, coming here people turn into stupid, greedy animals. At the sight of all these riches, they bare their teeth and go about like that until they either become millionaires or starve to death in the effort. Maxim Gorky, City of the Yellow Devil

It is important to remember that Mayakovsky and Gorky visited the United States before the Russian Revolution and before things went so terribly wrong. They were writing at time when there was great hope for positive change in Russia. Anyone who lived through what came in the next decades had a very different point of view.

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, artist unknown

The seven years of Lenin’s regime cost Russia from 8 to 10 million lives; it took Stalin ten years to add another 10 million, thus, according to Mr. Maximoff’s “very conservative estimate,” between 1917 and 1934 there perished about 20 million people, some being tortured and shot, others dying in prisons, others again falling in the Civil War… . The appearance of this tragic and terse book is especially welcome because it may help to dispose of the wistful myth that Lenin was any better than his successor. Vladimir Nabokov (quoted in Nabokov in America: On The Road To Lolita by Robert Roper)

Vladimir Nabokov, the famous author of Lolita, lived in America for roughly 20 years, from 1940-1960. He loved the country and adopted it as his own. He, like many who witnessed the dark side of the Russian Revolution, had no sympathy for communism or socialism even if the latter was qualified by the word “democratic.”

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, artist unknown

Nabokov liked all sorts of things about his adopted country, its trashy cultural ephemera as well as its natural beauty, its openness but also its odd conservatism, in which he perhaps sensed a different kind of opportunity (“what charms me personally about American civilisation,” he wrote to his agent before the move, “is exactly that old-world touch, that old-fashioned something which clings to it despite the hard glitter, and hectic nightlife, and up-to-date bathrooms”). His delight in it is beguiling, as is the image Roper offers of him as a particular kind of immigrant. Not an émigré in the mould of Thomas Mann or Bertolt Brecht, Nabokov immersed himself in the new place, not least via his work as an lepidopterist, through which he made all kinds of friends. Lidina Hass, The Guardian

For readers of Nabokov who want his opinion on literature, authors, and more TITM recommends two books based on his college lectures: Lectures on Literature (Austen, Dickens, Flaubert, Joyce, Kafka, Proust, Stevenson) and Lectures on Russian Literature (Chekhov, Dostoevski, Tolstoy, Turgenev, Gorki and Gogol). In 1964 Nabokov gave was interviewed by Alvin Toffler in Playboy where he offered his views on America, Russia and more.

Playboy: Though born in Russia, you have lived and worked for many years in America as well as in Europe. Do you feel any strong sense of national identity?

Nabokov: I am an American writer, born in Russia and educated in England where I studied French literature, before spending 15 years in Germany. I came to America in 1940 and decided to become an American citizen, and make America my home. It so happened that I was immediately exposed to the very best in America, to its rich intellectual life and to its easygoing, good-natured atmosphere. I immersed myself in its great libraries and its Grand Canyon. I worked in the laboratories of its zoological museums. I acquired more friends than I ever had in Europe. My books—old books and new ones—found some admirable readers. I became as stout as Cortez—mainly because I quit smoking and started to much molasses candy instead, with the result that my weight went up from my usual 140 to a monumental and cheerful 200. In consequence, I am one-third American—good American flesh keeping me warm and safe.

Playboy: You spent 20 years in America, and yet you never owned a home or had a really settled establishment there. Your friends report that you camped impermanently in motels, cabins, furnished apartments and the rented homes of professors away on leave. Did you feel so restless or so alien that the idea of settling down anywhere disturbed you?

Nabokov: The main reason, the background reason, is, I suppose, that nothing short of a replica of my childhood surroundings would have satisfied me. I would never manage to match my memories correctly—so why trouble with hopeless approximations? Then there are some special considerations: for instance, the question of impetus, the habit of impetus. I propelled myself out of Russia so vigorously, with such indignant force, that I have been rolling on and on ever since. True, I have lived to become that appetizing thing, a “full professor,” but at heart I have always remained a lean “visiting lecturer.” The few times I said to myself anywhere: “Now, that’s a nice spot for a permanent home,” I would immediately hear in my mind the thunder of an avalanche carrying away the hundreds of far places which I would destroy by the very act of settling in one particular nook of the earth. And finally, I don’t much care for furniture, for tables and chairs and lamps and rugs and things—perhaps because in my opulent childhood I was taught to regard with amused contempt any too-earnest attachment to material wealth, which is why I felt no regret and no bitterness when the Revolution abolished that wealth.

Playboy: You lived in Russia for 20 years, in West Europe for 20 years, and in America for 20 years. But in 1960, after the success of Lolita, you moved to France and Switzerland and have not returned to the U.S. since. Does this mean, despite your self-identification as an American writer, that you consider your American period over?

Nabokov: I am living in Switzerland for purely private reasons—family reasons and certain professional ones too, such as some special research for a special book. I hope to return very soon to America—back to its library stacks and mountain passes. An ideal arrangement would be an absolutely soundproofed flat in New York, on a top floor—no feet walking above, no soft music anywhere—and a bungalow in the Southwest. Sometimes I think it might be fun to adorn a university again, residing and writing there, not teaching, or at least not teaching regularly.

Nabokov did not return to America. He died in Switzerland in 1977 at age 78.

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, artist unknown

Another famous Russian writer, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, became Sinyavsky’s nemesis. There were many reasons but the main one was a disagreement on the responsibilities of an author. Solzhenitsyn felt an author should use his position to take political positions. Sinyavsky hated the “social realism” of the Stalin era and insisted the author’s only responsibility was to be true to his vision. Solzhenitsyn loved America. He would have been a Donald Trump fan because he had an unfortunate affinity for authoritarian rulers.

The Solzhenitsyn-Siniavskii clash was to become a defining feature of the third-wave Russian emigration. As lines were drawn between émigrés of more conservative persuasion like Solzhenitsyn and those of more liberal outlook such as Siniavskii, what can only be described as a feud swiftly developed between the two. (Andrei Siniavskii: A Hero of his Time?, Eugenie Markesinis)

Solzhenitsyn’s personal experiences (the war, labor camps, cancer) has kept him from achieving the sort of aesthetic distance that Sinyavsky was able to fashion for himself in his quiet, contemplative years at the Gorky Institute. Perhaps Solzhenitsyn’s moral passion for justice dictated his choice of form, in the belief that semi-documentary realism raised to the level of art was the best means of remaining true to the letter and spirit of the age. (Letters to the Future: An Approach to Sinyavsky-Tertz, Richard Lourie, p. 21)

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, TM artist

Author Kieth Gessen has this to say about Solzhenitsyn:

A whole ethics had grown up around Stalinism that was, at times, hard to parse. Solzhenitsyn, who had suffered so mildly in the camps, had declared the principle “Do not live a lie,” meaning, “Do not participate in the deceptions of the regime.” This would certainly include taking an apartment from Stalin for your work on a propaganda film and staying in it after the repressed former owner returned. My grandmother had lived a lie. But what did Solzhenitsyn do? He proclaimed his principle; he won the Nobel Prize; then in his later years he cozied up to Putin, surrendering in one widely televised smile (Putin came to visit him) the moral authority it had taken him fifty years to build. A Terrible Country, Kieth Gessen

Nabokov agreed with Solzhenitsyn about America but disagreed about the responsibilities of an author. Nabokov avoided taking political stands. Solzhenitsyn criticized him for it. With regard to content, Nabokov was closer to Sinyavsky but he did not like Sinyavsky’s style. Nabokov was a well-known curmudgeon when it came to other author’s works.

Inside Gessen’s book there is a statement about Putin that should give President Donald Trump pause:

Putin had worked as the deputy mayor there in the 1990s, before his move to Moscow and meteoric rise to the presidency. “He had dirt on everyone. That’s how he got people to do things. He had all the dirt.

It’s time to end this blog which has gone on too long. Maybe I’ll visit the subject again. I’ve taken a few diversions along the way but hey, isn’t that what traveling is all about? I’ll leave you with a song by Molly Marriott, daughter of Steve Marriott (Small Faces–Itchycoo Park). President Trump should pay close attention.

great research; the iggy pop meet-up with bourdain is precious; i knew iggy in ann arbor in 1966 and can attest to his legend being made very early in his astounding career while performing outrageous gigs at local high schols and concerts; thank you so much for all this! i hope folks in russia can access this?

Thanks Skip … the site is open but they have to find it

I came late to this one, but finally had a chance to watch ALL the videos and read ALL the text. You really outdid yourself. I discovered new material by a couple of my favorite performers–Michael Jackson and Billy Joel–and discovered a performer I hadn’t known about, Mollie Marriott. The videos were each gems, combining historic footage and rocket-fueled modern musical and visual creativity. The world loves rock ‘n’ roll, and rock ‘n’ roll IS America.

I dug the way you placed these videos in the midst of your astute commentary interspersed with visions of America through the eyes of wildly diverse Russians, including the meteoric genius Nabokov. I discovered books I absolutely must read. I dug Gorky’s view from 1906, pre-Russian-revolution, dug the astonishing range of opinion and observation of the writers and thinkers, their opinions of each other, of Russia and of America. Mayakovsky’s description of New York in 1925 is priceless, particularly what he had to say about Coney Island: “I have never seen such depravity stimulating such ecstasy.” At first I thought the word “stimulating” was a misprint, that it was supposed to be “simulating,” but then I realized “stimulating” was exactly what he meant. Back in those days, many “moral reformers” complained about the “depravity” of Coney Island, eliciting this terse rebuttal from one of its founding entrepreneurial fathers: “It ain’t no Sunday school.”

Excellent work. Now, if only Trump would direct the Russians to find your site the way he directed them to find Hillary’s emails!

You make me happy. Thanks very much.

Your insights need a wider audience.

Want to share on FB World Citizens United?

Or on http://www.OurVoices.org

Would love our global audience to learn your valuable perspectives.