“I do not think it is an overstatement that it appears just as important for California to have Mendocino preserved and guarded against encroachments as it was for Virginia to have Williamsburg restored and protected.” Civil History Chair of the Smithsonian Institution, December 1968

By the time I arrived in Mendocino in 1972, two of the most important environmental causes were well underway. I became aware of the Mendocino Conservation and Planning Foundation, a group formed in 1970 “active in the campaign to acquire the Mendocino Headlands and Ten Mile Dunes for inclusion in the State Park system to protect the areas from commercial and residential development.” I met several members and developed long term relationships with some, particularly Mildred Benioff, Lauren Dennen, and Bill and Gerry Grader.

“Geometry, Einstein said, is not inherent in nature. Our mind imposes it on nature.” Carlos Fuenrtes

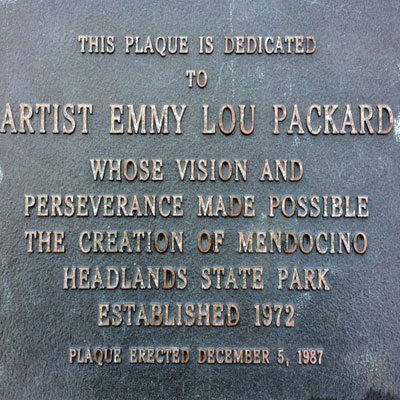

The locally owned Union Lumber Company sold the Mendocino Headlands to Boise Cascade, a national corporation, in 1968. Many Mendocino residents were concerned about plans by Boise Cascade to develop the headlands with a hotel, condos and other commercial development. One of these residents, artist and activist Emmy Lou Packard, spearheaded efforts to save the headlands with petitions and letter writing campaigns. A bronze plaque, located on the headlands at the west end of Main Street, credits her with the vision and persistence to preserve the headlands.

“When word got out (in the late 1960’s) that the [Mendocino] headlands were going to be developed by their lumber company owners, artist Emmy Lou Packard mobilized a citizens’ group which succeeded in preserving the open space that surrounds the town. Eventually, the Mendocino headlands became a state park and the entire town was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.” Via Magazine

I knew a little of Emmy Lou Packard from my time at U.C. Berkeley. The 85-foot-long concrete mural that is still in place on the Cesar Chavez Student Center at UC Berkeley, a bas relief made by Packard in 1959, is one of Emmy Lou Packard’s most enduring works of art. I admired it often during my time at Berkeley. The mural depicts California landscape features, including coastal bluffs, cultivated fields, mountains, and rivers. (Photo by Levi Bridges)

Emmy Lou Packard, Berkeley bas relief

Emmy Lou Packard, Berkeley bas relief

“Improvement makes strait roads, but the crooked roads without Improvement, are the roads of Genius.” William Blake

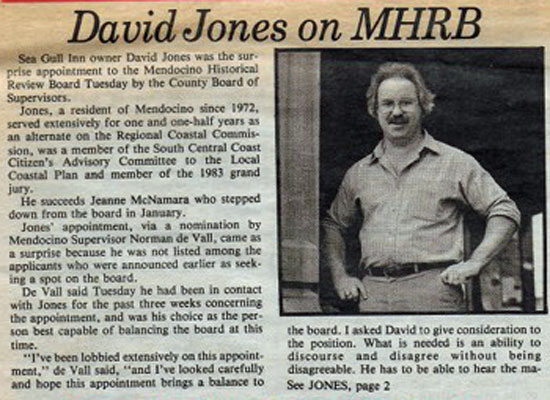

I had little idea at the time that meeting with the Mendocino Conservation and Planning Foundation would lead to my serving as an alternate to the California Coastal Commission, the Citizens Advisory Committee for the Mendocino Town Plan, and the Mendocino Historical Review Board. All I knew was that I admired Emmy Lou Packard for her art and for her activism and that the goal of saving the headlands appealed to me.

Emmy Lou Packard worked closely with the famous Mexican muralist Diego Rivera and his wife Frida Kahlo. At the age of 13, her mother took her to meet Rivera and his wife Frida. Rivera later recalled the beauty of the little girl “with the face of a French gothic angel plucked from the reliefs of Chartres.”

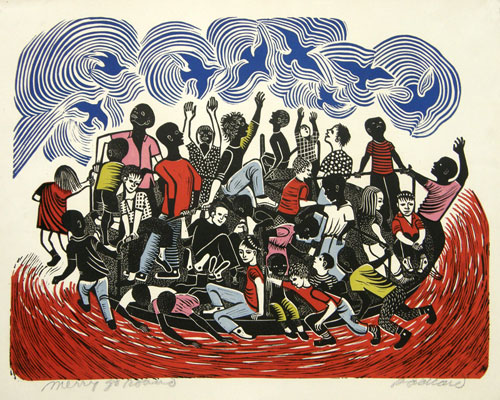

Emmy Lou Packard, Merry Go Round

Emmy Lou Packard, Peace is a Human Right

Years later that “little girl” met with William Penn Mott, Jr., the California State Parks Director appointed by Governor Ronald Reagan. This was the first of many long steps to save the Mendocino Headlands. With the ball beginning to roll, Packard turned over the laborious political job of drafting an historical ordinance and guiding it through the various County departments to her close friend, Mildred Benioff.

“Those people, who rallied around the idea of protecting [the headlands area] got me started on the idea of preserving the quality of Mendocino and getting the historic district set up. I felt it was the rather informal arrangement of everything — the little vacant spots in town where blackberry vines and nasturtiums were freely growing — which gave Mendocino a quality you don’t normally find anywhere. It wasn’t strictly formal but rather informal in character, kind of wild in a way.” William Penn Mott, Jr.

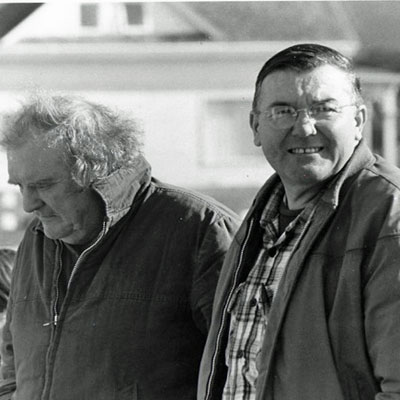

Byrd Baker and Jacques Helfer, photograph Nicholas Wilson

Not everyone was happy with the idea of an historical ordinance and a state park. “Basil Heathcote, Big River Judicial Court judge, was a vocal opponent who had a strong local following. Heathcote and fellow protesters also opposed the incorporation movement that was going on simultaneously. The opposition was angered by State Parks acting like “Big Brother,” telling them what to do with their town. If there was a demand for more commercial establishments, lodging and vacation homes, they argued they should “damn well be built.” And they certainly were not in favor of any new taxes. Some local residents even liked the idea of putting a hotel or resort on the headlands, saying, “It will give us a place to go dancing on Saturday night.” (Mendocino Beacon Part 1)

“Benioff remembers attending a county supervisors’ meeting to plead her case for the historic district ordinance and saving the headlands for a state park. Mott quoted her as saying, “It was the fourth time I’d made the 1.5-hour drive to Ukiah. He [Judge Basil] did all the talking and I was trying to get my turn, and one of the supervisors, who was the only woman on the board, said, Judge Heathcote, now it’s time we let the park lady speak.'” Benioff, who passed away in 2013, was known as the “Park Lady” from that moment on.” (Mendocino Beacon Part 2)

The Mendocino Historical Preservation Ordinance was passed in 1973, and that same year Mendocino was designated as a National Register Historical District. The Mendocino Headlands State Park opened the next year.

The opposition to the ordinance and the park did not end with the ordinance and the designation. Indeed, the arguments continue to this day. Environmental issues do not exist in a vacuum. They must be pursued as one of many of life’s concerns. My son, a forester, often reminds me that there’s a difference between conservation and preservation. Preservation is static while conservation is dynamic.

Mendocino’s resident naturalist, Jacques Helfer, wrote a weekly column for the Mendocino Beacon, Jacque’s Corner. More often than not he expressed loud criticism of the Historical Review Board, and he spoke for a certain local element who were annoyed and unhappy with what they deemed as unnecessary restrictions and outside influence. Ironically Helfer produced many interesting books on the nature and fauna of the Mendocino coast yet he opposed the government’s involvement in the efforts to conserve and protect the very resources that he personally claimed to cherish. Politics is seldom straightforward or easy.

While the save the headlands movement was progressing toward success, another movement was moving alongside it. John Olmsted was a naturalist, docent and educator at the Oakland Museum, UC Berkeley Extension and the Mendocino Art Center. Olmsted observed a unique geology and natural landscape along the Mendocino coast. At Jug Handle beach he found a rare living museum cascading upward and inland for two and a half miles where one million years of time and geologic uplift was visible in five terraces along what is now, after Olmsted’s hard work, the Jug Handle State Natural Reserve and Ecological Staircase Trail.

John Olmsted

“We can ramble on and teach ecology forever but the meaning really of this discussion is there’s a great deal of education to be done where nature makes her laboratories. They aren’t everywhere.” John Olmsted

In the 1960s the Jug Handle area was threatened with logging and real estate development. Conservationist John Olmsted worked extensively with pedologist Hans Jenny and local activists to preserve the farmhouse and the bluffs between 1968 and 1972, ending in a landmark lawsuit Burger v. Mendocino Board of Supervisors, involving the Pacific Holiday Lodge corporation, who had planned a motel on the bluffs overlooking the beach.

On September 29, 1972, Olmsted organized a team of attorneys, concerned citizens, and environmentally conscious residents to obtain an injunction against a group of developers who saw the Pigmy Forest as useless scrub brush. They had already started to destroy this one-of-a-kind geologic formation with bulldozers before the injunction could be issued.

“They had a shot at stopping things that shouldn’t start.” Attorney Doug Ferguson

In the years ahead, my early years at the Sea Gull, I grew to know John Olmsted quite well. He would often drift through needing a meal or a room or a donation to help keep his project going. I remember joining him with a small group on a walk up the staircase where he explained with clarity and passion all we saw around us. Silly as it might seem, I’ve kept one small poem tucked away in my mind over the years.

Sedges have edges

Rushes are round

Grasses are hollow

Right up from the ground.

There are many versions of this ditty but the one I remember is the one I learned from John Olmsted.

John’s son, Alden, made a beautiful video with music by Gene Parsons, The Story of Jughandle. The video can be viewed HERE and I encourage you to watch it.

Gene Parsons, an original member of the Byrds, performed at the Sea Gull Cellar Bar while I was there. I believe the most important characteristic to be successful at achieving any goal is to understand how to connect with your audience. While there were and still are differences of opinion about development and conservation, use and protection of resources, most people do connect to the natural beauty of the Mendocino coast.

“Too many artists are contemptuous of the public,” said Emmy Lou Packard. “Art which loses contact weakens.”

“Somehow at 25 years old I just knew that that was where I wanted to spend my life,” says Erica Fielder in the Jug Handle film. “People have to fall in love with a place. It has to become theirs. And that’s how it’s going to be protected.”

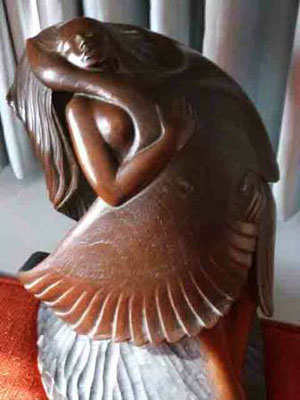

Leda and the Swan, James Sandberg

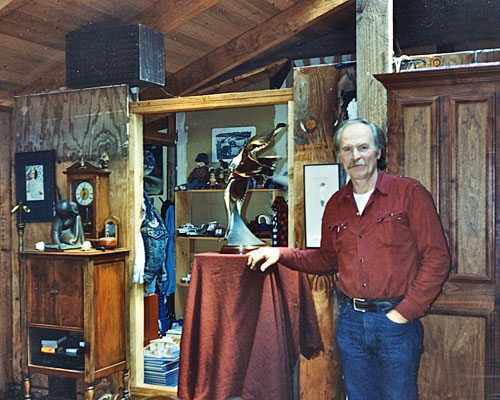

There is one more friend I must mention (there are many but that’s for another day) whose genuine delight in the natural world helped frame my own consciousness. James Sandberg was a quiet, unassuming man, a beautiful man, who made some of the most powerful and moving sculptures of wildlife I’ve ever seen. He would often come by the Sea Gull and we would talk about his work and the wildlife that inspired him.

James Sandberg, Eagle

One day Jim dropped by without warning as he was like to do. Something was troubling him. He had an awkward look in his eyes. He finally found the courage to speak what was on his mind. He had been offered a chance to travel to Alaska to study the animals he loved in the wild. It was, for him, a once in a lifetime opportunity. But, there was no money. Jim, among all people, was very reluctant to bring this up.

Jim Sandberg beside one of his sculptures, photo T. Johnson

He knew I liked his work although I had never been a collector. He proposed that I fund the trip up front and that, upon his return he would cast a bronze red-tailed hawk as a way to repay me. I was delighted with the idea. Hardly a day goes by that I don’t look at that hawk sitting in the family room of my house. It was a wonderful trade for both of us.

James Sandberg, Red Tailed Hawk

These are small stories, stories about how I was fortunate enough to connect with some incredibly talented people, and how I was able to watch some amazing things take place before my very eyes. I didn’t come to the Mendocino coast for a job or because I felt it was the right place to make big accomplishments. I came and I fell in love. I think of Mildred Benioff’s call home to her mother back East in Massachusetts after she’d seen the Southern California coast. “Ma, I’m not coming home.” I am home and I’m thankful for being there every day.

James Sandberg, self portrait 1977

Thank you David for all this and for all you are doing with

Think in the morning. It is so satisfying to read and see the photos of the important trials and joys along the way for our

wonderful village. It is a helpful reminder of how lucky we are to live in such a beautiful place. What you are doing here will hopefully be gathered together at some point for important memories in the story of Mendocino and of the Sea Gull too.

Thanks Cherie. My purpose with my website is exactly that, to gather a few memories before they fade. Who knows what purpose purpose this will serve, perhaps none. Putting the memories into words has its own worth for me.

Fascinating history, David. We also have a bronze of the Red Tail Hawk and we also have a black lacquered whale of Jim’s which we treasure.

Thank you Larry. Jim was a special man. I still miss hm.

WOW!!! David you’ve really outdone yourself with this post.. Great read and so much good information about our wonderful area and the folks who created what we sometimes take for granted about our little corner of the world. ..will share share share…

Loved your post! I own James Sandberg’s original sculpture: “LEDA and the SWAN.” Purchased in Mendocino in ’81, I think.

I wish to find a buyer–and thought “it belongs”

in Mendocino.” Perhaps the town or someone you know might be interested in purchasing it? (See contact info.). Thanks!