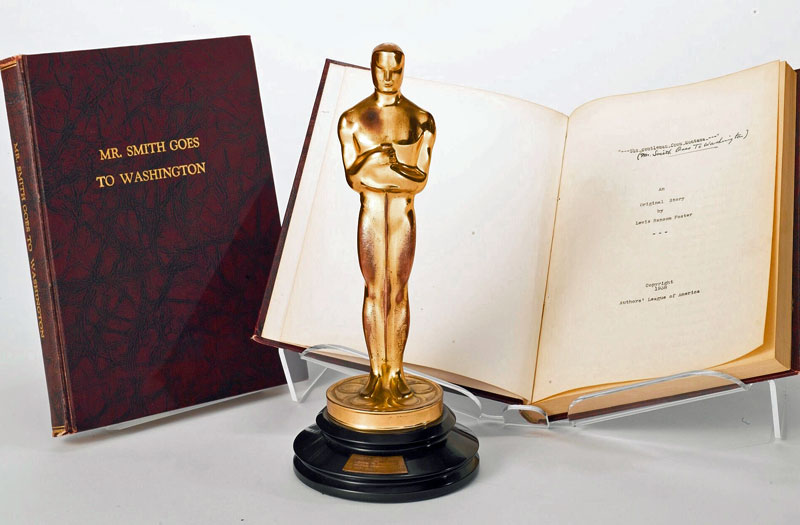

The 92nd Oscars® will be held tonight (February 9th) at 5 p.m. and aired on ABC. Why does it matter? For me, it’s personal. My great uncle, Lewis R. Foster, won an Oscar in 1939 for the best original story, The Gentleman From Montana. His story, unpublished, served as the basis for the critically acclaimed movie Mr. Smith Goes To Washington. The movie was nominated for 11 Academy Awards but earned only one, best original story for my uncle, and thereby launched his successful Hollywood career. He directed and wrote over 100 films and television series between 1926 and 1960. A few of the famous stars he worked with include Rhonda Fleming, Mickey Rooney, Agnes Moorehead, Ronald Reagan, Laurel and Hardy, Barbara Read, Dorothy Lamour, Dan Duryea, Edgar Bergen, James Stewart, Claude Raines, Dale Robertson, Deanna Durbin, Jean Arthur, Joel McCrea, Charles Durbin, and Betty Grable.

As you can see, this is a personal post, waxing nostalgic about my (great) uncle. I wrote briefly about him HERE and HERE.

Lewis died in 1974, just after I moved to Mendocino. I have many fond memories of him and his family. His wife, Dorothy Wilson, was a famed actress in her own right and a beautiful person. Lewis and Dorothy lived in Bel-Air, Los Angeles where I visited only once or twice. They visited me and my mother (a single parent) in Arbuckle (CA), hardly a mecca for the Hollywood crowd. They were Republicans, we were Democrats. They were Christian Scientists (Lewis converted after experiencing what he believed to be a miraculous cure for an illness), we were Catholics. They were wealthy, we were poor. In spite of the differences and distance between us, Lewis loved his sister (my grandmother) and made a point to visit when he could. Even after his death, Dorothy reached out and made us feel welcome.

I remember visiting the Walt Disney studio when my uncle worked there. I was thrilled to watch an episode of the Mickey Mouse Club being filmed, to meet Jimmie Dodd and a few of the Mouseketeers, and to see the trailers they lived in while filming the show. A kid’s dream, I got the autographs of Fess Parker (Davy Crockett), Sebastian Cabot (Westward Ho!), and Guy Williams (Zorro). I was about ten at the time.

I fought over sugar cookies (Uncle Lew always got the last one), learned to pop open coconuts and drink the milk, something I’d never seen before, had a chance to play the piano (at which I sucked), and rode around Bel-Air with Lewis in his car taking in the sights, a world I could only imagine. Yet, I dreamed.

I had little understanding of the magnitude of my uncle’s accomplishments at the time. Growing up in Arbuckle, my interests were sports, school, and girls. (Yes, I did meet Annette Funicello on that trip to Disney Studios).

I wish my uncle had lived to see my novel. Maybe he would have thought enough it to make a movie (smile). He certainly had the skills. Unfortunately it took 73 years to write my book and Lewis would have had to hold on until age 122. As it turned out, he died at 75. Dorothy lived until nearly 90. About 15 years before Dorothy died, she visited my mother and grandmother (Lewis’s sister) on the Mendocino coast. It’s the last time I saw her, still beautiful, still gracious.

I’ll be sending a high five to my uncle as I watch the Oscars tonight. I know it’s not what it used to be, but it’s still great to me. This is what Sotheby’s had to say about Lewis in 2012 when some of his possessions were sold by his family:

Within the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, 1939 is widely regarded as Hollywood’s greatest year, with some of the most beloved movies of all time amongst the Best Picture nominees —including The Wizard of Oz, Gone with the Wind, and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. Mr. Smith Goes to Washington was nominated for 11 Academy Awards including Best Picture, but because of the intense competition, it came away with one Oscar, the Oscar awarded to Lewis Ransom Foster for the original story behind Frank Capra’s “stirring and even inspiring testament to liberty and freedom, to simplicity and honesty and to the innate dignity of just the average man” (Frank S. Nugent, New York Times Review, 20 October 1939).

Formerly a newspaper journalist in San Francisco, Lewis R. Foster entered Hollywood in 1923 as a prop man. In 1929, he directed his first movie and throughout his prolific, 36-year career, he continued to direct, compose music and write screenplays. Foster penned the original story for Mr. Smith, titled The Gentleman from Montana and obtained the copyright in 1938. While it does differ from the final screenplay, the storyline and main characters are defined clearly in the unpublished novel. Foster tells the story of Scout Master John Wilbur Smith who, following the death of Senator Foley, is selected by the Governor and his political cronies to temporarily replace him for three months during the Congressional Session. Patriotic, passionate and naïve, Senator Smith finds the political system in Washington, D.C. “something rotten and decayed, boiling corruption like a sore” (The Gentleman from Montana, pg. 62). The graft in the political system is anathema to his old-fashioned American values, but despite his disappointment and heartbreak, Smith stands up to the system and reminds the Senate and the citizens of the real meaning of democracy.

The explicit criticism in The Gentleman from Montana initially prompted a warning from Joseph Breen, the director of the Production Code Administration, in which he suggested that the subsequent movie “might well be loaded with dynamite … which might well lead to such a picture being considered, both here, and more particularly abroad, as a covert attack on the Democratic form of government.”

The warning was given after both MGM and Paramount submitted Foster’s unpublished novel for approval, but it was Columbia that won the rights to the story. Frank Capra was selected to be the director and it was first conceived of as a sequel to Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, starring Gary Cooper. When Cooper was unavailable, Capra brought in James Stewart from MGM, and Stewart inaugurated his now familiar role as the stalwart idealist. Sidney Buchman turned the original story into a screenplay, changing John Wilbur Smith into Jefferson Smith, introducing a more consciously comedic element, and de-emphasizing the corruption of the government to comply with censorship restrictions. Breen revised his earlier critique of the film, pointing out that “Out of all Senator Jeff’s difficulties there has been evolved the importance of a democracy and there is splendidly emphasized the rich and glorious heritage which is ours and which comes when you have a government ‘of the people, by the people, and for the people.’” Even so, in Capra’s autobiography he recounts that during the 17 October 1939 premier of the movie at Constitution Hall, disgruntled senators walked out of the theater, and Senate Majority Leader Alben W. Barkley insisted that the film “makes the Senate look like a bunch of crooks.”

Seen as a movie that restores faith in democracy and emphasizes the perseverance and strength of one man standing up to injustice, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is consistently listed as one of the best political movies of all time and has been called “the top Washington-related movie” by the Washington Post.

How proud Lewis would have been to read this tribute some 70 years after the movie. Those were the days. We need them back. Let’s hope.

Thank you …that was good writing and a excellent personal history review .

This is brilliant David, “Mr. Smith …” this is one of my most favorite movies as well. You bring a wellspring of information and affections to keep in mind what is going on today.

Sending resounding cheers to you.

what a full flavored tale; swallowed whole w/o much chewing (till i flashed back on annette f); thanx – will share at the oscar parties tonite……

How exciting about your family!

I, too, held an Oscar that a friend’s father got as a documentarian. He actually got two; so, each of his two daughters have one. However, his daughter had to flee Hollywood as the MacArthur hirings were going on and her mother was followed down to Mexico by the FBI. While in Mexico on a visit I got to hold the golden Oscar. I was thrilled; however, the terror of the McCarthy error hung over us while down there. By the way, an Oscar is very heavy!

Rhoda

Heavy in many ways.

Fascinating. It has been said that the main character was based on Senator Burton K. Wheeler. Do you know it that is true?