Death always leaves one singer to mourn.

In 1918 Katherine Anne Porter was 28 years old working for the Rocky Mountain News in Denver Colorado. A young soldier lived in her boarding house while waiting to be deployed overseas. They became close and spent much of their free time together. World War I consumed the news and they both knew their relationship together was limited. Meanwhile an invisible enemy, a dangerous influenza that would eventually kill more Americans than all the wars of the twentieth century, began to manifest its evil designs all around them. Porter contracted the deadly virus and it nearly killed her. She was expected to die. Her obituary was written. She spent several fevered days and nights on a gurney in a hospital hallway for lack of rooms and beds. Her hair fell out and when it grew back later it had turned pure white and stayed that way for the rest of her life. The soldier who nursed her faithfully in the early stages of her disease died of influenza soon after being deployed to France while she was still in the hospital. Many years later she wrote about her experiences at this time in what may be her best story, the title story of a trilogy she called Pale Horse, Pale Rider. It is a fictional description of living with and in the time of a deadly pandemic that resonates today in this shadowy time of COVID 19. (NOTE: All the italicized quotes below are from the Porter short story Pale Horse, Pale Rider.)

“Let’s sing,” said Miranda. “I know an old spiritual, I can remember some of the words.” She spoke in a natural voice. “I’m fine now.” She began in a hoarse whisper, “‘Pale horse, pale rider, done taken my lover away. . .’ Do you know that song?” “Yes,” said Adam, “I heard Negroes in Texas sing it, in an oil field.” “I heard them sing it in a cotton field,” she said; “it’s a good song.” They sang that line together. “But I can’t remember what comes next,” said Adam. “‘Pale horse, pale rider,’” said Miranda, “(We really need a good banjo) ‘done taken my lover away—’” Her voice cleared and she said, “But we ought to get on with it. What’s the next line?” “There’s a lot more to it than that,” said Adam, “about forty verses, the rider done taken away mammy, pappy, brother, sister, the whole family besides the lover—” “But not the singer, not yet,” said Miranda. “Death always leaves one singer to mourn. ‘Death,’” she sang, “‘oh, leave one singer to mourn—’” “‘Pale horse, pale rider,’” chanted Adam, coming in on the beat, “‘done taken my lover away!’ (I think we’re good, I think we ought to get up an act—)”

Volumes have been written about Katherine Anne Porter’s Pale Horse, Pale Rider. I need not repeat the accolades and analyses here. I’ve listed a few sources below if you wish to follow up. The best source is the story itself. The story describes how a pandemic impacted the lives of two young people and the experience can be extended to us all. It was based loosely on actual events. Years after she wrote the story, Porter said in an interview: “It simply divided my life, cut across it like that. So that everything before that was just getting ready, and after that I was in some strange way altered.”

There are interesting similarities between Porter’s story and the times we are in today. There is a dreamlike quality of life in the time of a pandemic. Porter uses dreams and deliriums throughout her story to express this airy feeling of living in a fog. In the very first scene Miranda, the central character, has a premonition of death and also of hope.

The stranger rode beside her, easily, lightly, his reins loose in his half-closed hand, straight and elegant in dark shabby garments that flapped upon his bones; his pale face smiled in an evil trance, he did not glance at her. Ah, I have seen this fellow before, I know this man if I could place him. He is no stranger to me … I’m not going with you this time—ride on! Without pausing or turning his head the stranger rode on.

Later, near the end of the book, Porter describes the delirium brought on by Miranda’s fever. The dual enemies of war and influenza are confounded as they work on her at the same time.

Across the field came Dr. Hildesheim, his face a skull beneath his German helmet, carrying a naked infant writhing on the point of his bayonet, and a huge stone pot marked Poison in Gothic letters. He stopped before the well that Miranda remembered in a pasture on her father’s farm, a well once dry but now bubbling with living water, and into its pure depths he threw the child and the poison, and the violated water sank back soundlessly into the earth. Miranda, screaming, ran with her arms above her head; her voice echoed and came back to her like a wolf’s howl, Hildesheim is a Boche, a spy, a Hun, kill him, kill him before he kills you. . . . She woke howling, she heard the foul words accusing Dr. Hildesheim tumbling from her mouth; opened her eyes and knew she was in a bed in a small white room, with Dr. Hildesheim sitting beside her, two firm fingers on her pulse. His hair was brushed sleekly and his buttonhole flower was fresh. Stars gleamed through the window, and Dr. Hildesheim seemed to be gazing at them with no particular expression, his stethoscope dangling around his neck. Miss Tanner stood at the foot of the bed writing something on a chart. “Hello,” said Dr. Hildesheim, “at least you take it out in shouting. You don’t try to get out of bed and go running around.”

Pandemics bring out our biases—racial, cultural, political and other. Conspiracy theories abound in the general ignorance that accompanies any new or unfamiliar threat. The “Spanish” flu may have originated in Kansas. Our President likes to call the Coronavirus the “Chinese” virus. It does appear to have originated in China but all the facts are not in yet. For many, it doesn’t matter as long as they can blame someone or something other than themselves.

“They say,” said Towney, “that it is really caused by germs brought by a German ship to Boston, a camouflaged ship, naturally, it didn’t come in under its own colors. Isn’t that ridiculous?” “Maybe it was a submarine,” said Chuck, “sneaking in from the bottom of the sea in the dead of night. Now that sounds better.” “Yes, it does,” said Towney; “they always slip up somewhere in these details. . . and they think the germs were sprayed over the city—it started in Boston, you know—and somebody reported seeing a strange, thick, greasy-looking cloud float up out of Boston Harbor and spread slowly all over that end of town. I think it was an old woman who saw it.”

The fantasy of a miracle cure inevitably arises when a real cure is yet to be found. Today it’s Donald Trump embracing chloroquine. Susan Sontag pointed out in Illness as Metaphor and AIDS and It’s Metaphors that metaphors and myths are dangerous because they “make people irrationally fearful of effective measures such as chemotherapy, and foster credence in thoroughly useless remedies such as diets and psychotherapy.” She writes about fake tuberculosis cures: “With these weapons we will conquer tuberculosis” the figure of death is shown pinned to the wall by drawn swords, each of which bears an inscription that names a measure to combating tuberculosis. Cleanliness is written on one blade. Sun on another, air, rest, proper food, hygiene. (Of course, none of these weapons was of any significance, what conquers, that is, cures, tuberculosis is antibiotics, which were not discovered until some twenty years later, in the 1940s.)” There is a passage in Pale Horse, Pale Rider that plays on this fantasy when Adam gives Miranda her medicine. Miranda seems to know the available cures are worthless as she laughs uncomfortably after vomiting the pills.

“I’ve got your medicine,” said Adam, “and you’re to begin with it this minute. She can’t put you out.” “So it’s really as bad as that,” said Miranda. You’re running a risk,” she told him, “don’t you know that? Why do you do it?” “Never mind,” said Adam, “take your medicine,” and offered her two large cherry-colored pills. She swallowed them promptly and instantly vomited them up. “Do excuse me,” she said, beginning to laugh. “I’m so sorry.” Adam without a word and with a very concerned expression washed her face with a wet towel, gave her some cracked ice from one of the packages, and firmly offered her two more pills. “That’s what they always did at home,” she explained to him, “and it worked.” Crushed with humiliation, she put her hands over her face and laughed again, painfully. “There are two more kinds yet,” said Adam, pulling her hands from her face and lifting her chin. “You’ve hardly begun. And I’ve got other things, like orange juice and ice cream—they told me to feed you ice cream—and coffee in a thermos bottle, and a thermometer. You have to work through the whole lot so you’d better take it easy.”

One of the first reactions as a new disease emerges is to try to ignore it or blame it on something other than what it is.

She had a burning slow headache, and noticed it now, remembering she had waked up with it and it had in fact begun the evening before. While she dressed she tried to trace the insidious career of her headache, and it seemed reasonable to suppose it had started with the war.

People panic when they see what’s going on. Miranda’s landlady Miss Hobbe threatens to throw her out on the sidewalk if she cannot be transported to the hospital even though there are no rooms or beds available for her. Hospital capacity is another common issue that quickly arises in a pandemic.

“I tell you, they must come for her now, or I’ll put her on the sidewalk. . . I tell you, this is a plague, a plague, my God, and I’ve got a houseful of people to think about!”

Disease can approach with lightening speed but death is more often a long, slow, agonizing process. Increasing numbers of funeral processions and shut businesses are the signs that something awful is amiss. At first the implications are ignored.

They stood while a funeral passed, and this time they watched it in silence. Miranda pulled her cap to an angle and winked in the sunlight, her head swimming slowly “like goldfish,” she told Adam, “my head swims. I’m only half awake, I must have some coffee …”

“… It’s as bad as anything can be,” said Adam, “all the theaters and nearly all the shops and restaurants are closed, and the streets have been full of funerals all day and ambulances all night—” “But not one for me,” said Miranda, feeling hilarious and lightheaded. She sat up and beat her pillow into shape and reached for her robe. “I’m glad you’re here, I’ve been having a nightmare.

Until you personally become sick, it’s easy to disbelieve the signs that surround you, to revolt, to carry on as if things were normal.

The men are dying like flies out there, anyway. This funny new disease. Simply knocks you into a cocked hat.” “It seems to be a plague,” said Miranda, “something out of the Middle Ages. Did you ever see so many funerals, ever?” “Never did. Well, let’s be strong minded and not have any of it. I’ve got four days more straight from the blue and not a blade of grass must grow under our feet. What about tonight?” …

… they put off as long as they could the end of their moment together, and kept up as well as they could their small talk that flew back and forth over little grooves worn in the thin upper surface of the brain, things you could say and hear clink reassuringly at once without disturbing the radiance which played and darted about the simple and lovely miracle of being two persons named Adam and Miranda, twenty-four years old each, alive and on the earth at the same moment …

The end of their moment together did come. Miranda made an unexpected recovery on her gurney in the overcrowded hospital apparently due to an experimental shot of strychnine. She discovered later reading through a pile of letters brought to her bedside that Adam died in France of the influenza from which she somehow escaped.

The story is a rare glimpse into the private lives of a young couple thrown together by chance and torn apart by a cruel randomness inflicted on the human race when least expected. War is the absurdity we inflict upon ourselves, a human flaw Porter abhors as she makes clear in her story. Pandemics are nature’s way of reminding us that death is just around the corner. But, death always leaves one singer to mourn. Let’s hope that is so today and in the future.

Oblivion, thought Miranda, her mind feeling among her memories of words she had been taught to describe the unseen, the unknowable, is a whirlpool of gray water turning upon itself for all eternity. . . eternity is perhaps more than the distance to the farthest star. She lay on a narrow ledge over a pit that she knew to be bottomless, though she could not comprehend it; the ledge was her childhood dream of danger,

and she strained back against a reassuring wall of granite at her shoulders, staring into the pit, thinking, There it is, there it is at last, it is very simple; and soft carefully shaped words like oblivion and eternity are curtains hung before nothing at all. I shall not know when it happens, I shall not feel or remember, why can’t I consent now, I am lost, there is no hope for me. Look, she told herself, there it is, that is death and there is nothing to fear. But she could not consent, still shrinking stiffly against the granite wall that was her childhood dream of safety, breathing slowly for fear of squandering breath, saying desperately, Look, don’t be afraid, it is nothing, it is only eternity. Granite walls, whirlpools, stars are things. None of them is death, nor the image of it. Death is death, said Miranda, and for the dead it has no attributes. Silenced she sank easily through deeps under deeps of darkness until she lay like a stone at the farthest bottom of life, knowing herself to be blind, deaf, speechless, no longer aware of the members of her own body, entirely withdrawn from all human concerns, yet alive with a peculiar lucidity and coherence; all notions of the mind, the reasonable inquiries of doubt, all ties of blood and the desires of the heart, dissolved and fell away from her, and there remained of her only a minute fiercely burning particle of being that knew itself alone, that relied upon nothing beyond itself for its strength; not susceptible to any appeal or inducement, being itself composed entirely of one single motive, the stubborn will to live. This fiery motionless particle set itself unaided to resist destruction, to survive and to be in its own madness of being, motiveless and planless beyond that one essential end. Trust me, the hard unwinking angry point of light said. Trust me. I stay.

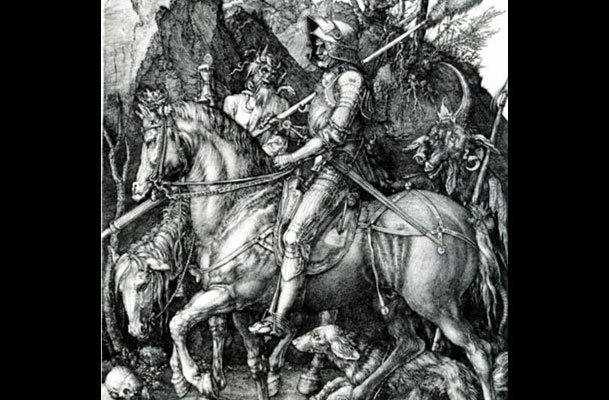

Albrecht Dürer: Knight, Death and the Devil

BOOKS:

Katherine Anne Porter and Mexico: The Illusion of Eden

Thomas F. Walsh, Chapter 6: Becoming Miranda

Viral Modernism: The Influenza Pandemic and Interwar Literature

Elizabeth Outka, Chapter 2: Untangling War and Plague

Willa Cather and Katherine Anne Porter

AN ASIDE:

Katherine Anne Porter translated The Itching Parrot (El Periquillo Sarniento) by José Joachín Fernández de Lizardi. (I briefly mention Lizardi in my novel Behind The Locked Door). In her introduction she writes that Lizardi provided the following advice on how to deal with plagues over 200 years ago.

One of its periodic plagues came upon Mexico City and raged as usual, and the churches were crowded with people kissing the statues and handing on the disease to each other. In one number of The Thinker , Lizardi advised them to clean up the streets, to burn all refuse, to wash the clothes of the sick not in the public fountains but in a separate place, not to bury the dead in the churches, and as a final absurdity, considering the time and place, he counseled them to use the large country houses of the rich as hospitals for the poor. None of these things was done, the plague raged on and raged itself out. From: Notes on the Life and Death of a Hero Introduction to The Itching Parrot (El Periquillo Sarniento ), by José Joachín Fernández de Lizardi (The Mexican Thinker), translated from the Spanish by Katherine Anne Porter. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Doran & Co., 1942. (Reprinted in: The Collected Stories of Katherine Anne Porter).

Thank you…….for your piece………and references……