Written over fifteen years ago, Oliver Sacks’ Oaxaca Journal is still one of the best books for visitors to Oaxaca. I was confused to read that one reviewer thinks that: “Sacks did not go into the depth I might have expected based on the insight he displayed in previous books.” I have no idea what that reader was talking about. Having just returned from a month in Oaxaca, I remain convinced that Oliver Sacks’ book is a wonderful short guide for anyone travelling there. He covers an amazing array of topics and delves into them with his characteristic curiosity and razor sharp eye. Does he make mistakes? Certainly. But why dwell on a few oversights or confusions when he gives us so much to appreciate, ponder and love about Oaxaca?

Even when writing about ferns, the purpose of his trip with the American Fern Society, Sacks provides a number of fascinating asides that pull the reader along whether or not the reader has an interest in the flora and fauna of the area. For example, consider this anecdote on the bracken, a harmless looking green fern that nearly everyone has seen at one time or another.

Animals that eat bracken may develop the “bracken-staggers,” because bracken contains an enzyme, thiaminase, which destroys the thiamine necessary for normal conduction in the nervous system. As a neurologist, this intrigues me, for such animals may lose their coordination and stagger, or show “nervousness” or tremor and if they continue to eat the bracken, they will get convulsions and die… But this, I now find, is only a tiny part of bracken’s repertoire. Robbin calls bracken “the Lucrezia Borgia of the fern world,” for it packs a series of horrors for the insects that eat it. The young fronds release hydrogen cyanide as soon as the insect’s mandible tears into them, and if this does not kill or deter the bug, a much crueler poison lies in store. Brackens, more than any other plant, are loaded with hormones called ecdysones, and when these are ingested by insects, they cause uncontrollable molting. In effect, as Robbin puts it, the insect has eaten its last supper.

Timothy Leary fans will be amused by another piece of priceless information. I remember reading about this in an article by Sacks in the New Yorker.

Among my fern-loving fellow travelers, however, there are quite a few experts on flowering plants too—J.D. and Scott among them—and now, on the bus, as we pass by some trees laden with glorious white flowers, Scott draws our attention to them. These, he says, are tree Ipomoea. Ipomoea, I query? The same genus as the morning glory? Yes, says Scott, the sweet potato, too. I think back to my California days, in the early 1960s, when morning glory seeds—one variety of them, at least (the “Heavenly Blue”)—were used for their psychedelic power—since they contained ergot compounds, lysergic acid derivatives, similar to LSD. I used to get three or four packets of the hard, angular black seeds, pound them to powder with a mortar and pestle, then—this was my special innovation—mix the ground seeds with vanilla ice cream. There would be intense nausea for a while, followed by visions of a very personal heaven or hell. I often wished for the right place and time to take it—and this would have been in south Mexico, where the morning glory grows easily and abundantly in the mountains, and its seeds, ololiuhqui, can be kept indefinitely without losing their potency. Indeed, I am told, the plant itself (which the Aztec called coatlxoxo-uhqui, green-snake, for its twining vinelike habit) was regarded as a sacramental plant, and used in the presence of a medicine man, a curandero.

Classic Oliver Sacks, immediately recognizable by anyone familiar with his writing. It is these personal stories and musings that make his Oaxaca Journal, like his other books, enjoyable and informative for the casual tourist and professional alike.

The cochineal insect lives in the small white cocoons on the leaves and berries.

He writes about the origin of the word cigar (from the Mayan word for smoking sik’ar), about chocolate factories and cacao beans, and about the cochineal insect that gives rise to the red dye used in many Oaxacan textiles.

When the Spaniards first saw cochineal they were amazed—there existed no dye in the Old World of such a rich redness and fullness, and so colorfast, so stable, so impervious to change. Cochineal, along with gold and silver, became one of the great prizes of New Spain, and weight for weight, indeed, was more precious than gold.

He points out that beans and corn contain all the amino acids one needs for good health, provides a short history of Benito Juarez, discusses the benefits and dangers of eating insects (“swallow three fireflies, it is said, and you’re a goner”).

Woman selling grasshoppers in buckets at Llano Park market

Of the many new foods I have eaten in the past days, the grasshoppers have pleased me especially—crunchy, nutty, tasty, and nutritious; they are usually fried and spiced. Grasshoppers, by a special biblical dispensation, are kosher, unlike most invertebrates. (Did not John the Baptist live on locusts and wild honey?) This alwauys seemed to me a reasonable, even necessary, dispensation, for life in ancient Israel was quite chancy, and locusts, like manna, were a godsend in lean times. And locusts could come in unaccountable millions, wiping out the always precarious harvests of the time. So it seemed only just, a poetic and nutritional justice, that some of these voracious eaters be eaten themselves.

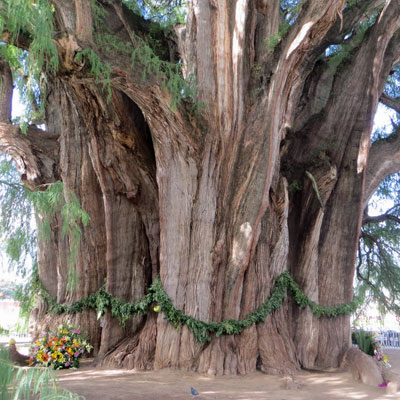

Tule Tree, Marcia Schirber photographer

He mentions and comments on numerous sites and items still popular with visitors to Oaxaca today (Conzatti Park, the Tule Tree, Yagul, the Zocalo, Mezcal, black pottery, the first rubber balls used in the ball courts of Monte Alban, the petrified waterfalls at Hierve el Agua, among others).

Yagul Ruins

Hierve el Agua Mineral Springs

Hierve el Agua petrified waterfall

At one point, speaking of the mineral springs and frozen waterfalls at Hierve el Agua, he exclaims:

It is an amazing simulacrum of a waterfall consisting not of water but of mineral calcite, yellowish-white, hanging in vast rippling sheets from the cliffs above.

Later, while sitting alone in the zocalo, he waxes nostalgic:

I found a little table at an outdoor cafe in the zocalo. The cathedral, noble, dilapidated is to my left and this charming alive plaza is full of handsome young people and cafes. Writing, like this, at a cafe table, in a sweet outdoor square … this is la dolce vita.

Zocalo Cafe

I agree !

Zocalo looking from Cathedral

Zocalo looking north

The disappointed reviewer quoted earlier was particularly offended by Oliver Sacks comments on the front plaza of Santo Domingo Church: an “uncanny red-earthed Martian plantscape”. It’s a fair criticism that Sacks wasn’t thinking ahead. What he saw in 2002 turned into a beautiful garden 15 years later. But if you look at what he saw when he was in Oaxaca, his comment is understandable if shortsighted.

Botanical Garden in 2001

Botanical Garden in 2016

Santo Domingo Plaza in 2001

Santo Domingo Plaza in 2016

Oaxaca Journal is full of beautiful observations some of which he hears from his friends. As a novice mathematician, I particularly like this one:

If you don’t know about Fibonacci series, how can you truly appreciate a pinecone?

While visiting the spectacular cultural museum inside the old convent at Santo Domingo Church, Sacks detours into a discussion about the fragility of books.

Biblioteca in Mexico City

We stop first in the museum’s biblioteca, a long, long room, and high, stacked up to the ceiling with incunabula and early calf-bound books. There is a sense here of great learning, of tranquility, of the immensity of history, and of the fragility of books and paper. It was the fragility that made it possible for the Spanish to destroy the written records of the Maya and the Aztec and preceding civilizations almost completely. Their exquisite, delicate, manuscript books of bark had no chance of surviving the conquistadors’ autos-da-fe, and they were destroyed by the thousands—barely half a dozen remain. The writings and glyphs inscribed on the statues and temples and tablets and tombs were somewhat less vulnerable, but many of these are still indecipherable to us, or largely so, despite a century of work. Gazing at the fragile books in this library, I think of the great library of Alexandria, with its hundreds of thousands of unique, uncopied scrolls, whose burning lost forever much of the knowledge of the ancient world.

A popular archeological site in Oaxaca although overshadowed by Monte Alban, is the beautiful set of ruins known as Yagul. Sacks describes his arrival at Yagul with his characteristic sense of awe and humor.

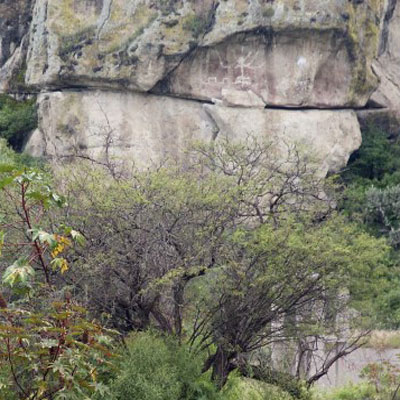

Guilá Naquit Cave Petroglyph

As we approach Yagul, Luis points out a cliff face with a huge pictograph painted in white over a red background, an abstract design; and above it a giant stick figure, a man. It looks remarkably fresh, almost new—who would guess it was a thousand years old? I wonder what the image means: Was it an icon, a religious symbol of some kind? A warning to evil spirits, or invaders, to keep away? A giant road sign, perhaps, to orient travelers on their way to Yagul? Or a pure, for-the-love-of-it pictographic doodle, a prehistoric piece of graffiti?

Sacks and possibly his guide, Luis, apparently did not know that the petroglyph he sees marks the opening to the Guilá Naquitz cave, an oversight but certainly not fatal to the book. Archaeologists have found nearly 100 caves and rock shelters in the Central Valley of Oaxaca near the ancient cities of Yagul and Mitla. They contain evidence of pre-historic human habitation. Many contain paintings and other rock forms of graphic representation. Several of their contents include ceramics and stone tools. The Guilá Naquitz cave has some of the best evidence for the domestication of corn and squash which dates back more than 10,000 years. Human occupation of the caves dates back to 8000 BCE. He would have loved to know about this I’m sure and many other things as well which is why he says at the end of his book that he will read more about Oaxaca and hopefully return.

Yagul viewed from above

King’s Tombs at Yagul

Sacks is deeply affected by what he sees on his short visit to Oaxaca.

“The power and grandeur of what I have seen has shocked me, and altered my view of what it means to be human.”

Monte Alban 2001

Monte Alban 2016

Yet, he recognizes and points out that not everything in Oaxaca is to be admired. Like any large city, Oaxaca has a downside. His description, though not nearly as dark, made me think of Malcolm Lowry’s famous book Under the Volcano.

An early morning walk near our hotel with Dick Rauh and his wife went astray this morning. We got lost, and almost killed, trying to cross the Pan American Highway. We saw open sewers, children with infected eyes and sores. Fearful poverty, filth. We were almost asphyxiated by diesel fumes; we were almost bitten by a ferocious, perhaps rabid dog. This is the other side of Oaxaca, a modern city, full of traffic, with a rush hour and poverty, like any other. Perhaps it is salutary for me to see this other side, before I get too lyrical about this Eden.

Don’t let this deter you from walking in Oaxaca. It is a wonderful walking town and not all dogs are a menace.

Dog taking a break in Llano Park

Sleeping dogs near Santo Domingo Church

Oliver Sacks did not let the “other side of Oaxaca” spoil his visit. Not at all.

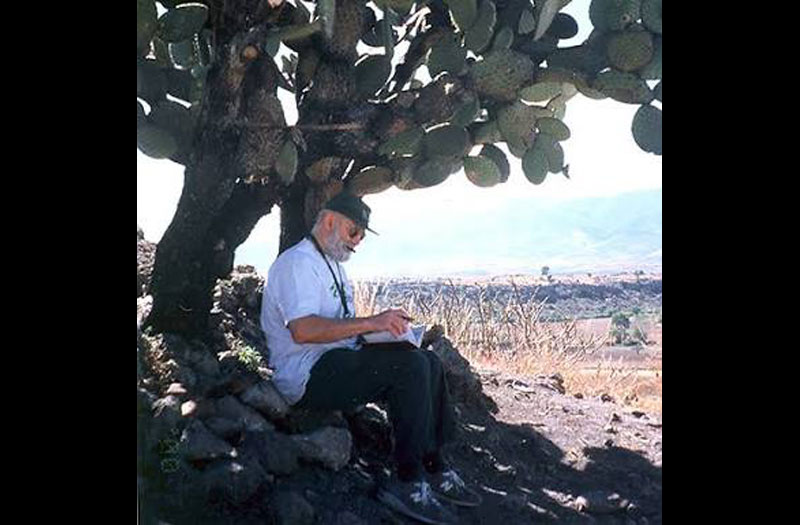

Monte Alban, above all, has overturned a lifetime of presuppositions, shown me possibilities I never dreamed of. I will read Bernal Diaz and Prescott’s 1843 Conquest of Mexico again, but with a different perspective, now that I have seen some of it myself. I will brood on the experience, I will read more, and I will surely come again.

Unfortunately Oliver Sacks did not make another trip to Oaxaca. He’s gone and we are surely poorer for that. There will never be another like him. I go whenever I can to Oaxaca. I’m always happy when I’m there. And I always think of Oliver Sacks when I’m there.

Wilson’s Warbler at Bugambilias, photo Marcia Schirber

Two Girls in a Guelaguetza Parade, photo Marcia Schirber

Golden Lion of Llano Park gazing at the closed Templo de Nuestra Señora del Patrocinio, photo Marcia Schirber

Well reviewed and beautifully presented.

Thanks for your recommendation, I’m going to see if I can find it! 🙂

I came back to this while studying blog building and enjoyed it very much, enough to send it along to friends who love Mexico and Oliver, whom Tomar knew from his days in a LA gym.

Beautifully described. A great tribute to Oaxaca and Oliver Sacks. A better insight. Love the before and after photos. Thank you.