But ask now the beasts, and they shall teach thee; and the fowls of the air, and they shall tell thee. Job 12-7

Tictetzoa in chalchihuitl, ticoaoazoa in quetaxlli

You have scratched the jade, you have torn apart the quetzal feather. Aztec metaphor, Thelma D. Sullivan translator

Paul and Edith bought their first alebrijes from Pepe Gonzalez in the small town of San Antonio Arrazola just outside the city of Oaxaca in southern Mexico-a lion, an iguana and a rhinoceros, animals carved out of copal wood.

They were told that the intricate wood carvings represent actual creatures that live in our dreams and are connected to our spirits. “They are sometimes called nuhuales,” said Mr. Gonzalez, a Zapotec man with coal black hair, mustache and chocolate brown skin.

“They act as personal guides or protectors. Some believe that people with special powers can transform into their nahual at night but I have never seen that.”

Gonzalez’s smile made Paul wonder if the artist was pulling his leg. But then a deadly fierce look came over Gonzalez whose piercing brown eyes caused Paul’s heart to race.

“Your nahual, my friend, I see …” Gonzalez stopped midsentence.

“What do you see?” said Paul.

“Nothing, my friend” said Gonzalez. “Vaya con Dios.”

Pepe Gonzalez said no more. He turned abruptly and went inside his studio.

That was more than twenty years ago. Since then their collection has grown and grown. They now have hundreds of alebrijes scattered throughout their rambling country house. An amazing menagerie of animals, birds, fish and fantastic chimeras interspersed with Edith’s ferns, succulents, and miscellaneous house plants. When friends visit they say with a laugh: “those Greenes, they live in a South American jungle.”

Paul grew up in a small farming town. Though he left long ago, the small town no-nonsense values he learned early stuck with him. But, not religion. He left that behind. He had a distaste for the supernatural, for the occult, for gurus, for “new age bullshit” as he called such things. He didn’t believe in personal spirit guides or animal protectors but the alebrijes amused him and he liked having them around.

The carved animals were painted with colors using natural dyes the artists made from local plants and minerals. Green was believed to conjure up nature and empathy, red expressed passion and love, blue engendered tranquility, brown the earth, orange assisted in the liberation of negative emotions while yellow invoked happiness and light. So the artists said.

Paul was familiar with how color can stimulate the senses. He once owned a restaurant. Red makes people eat faster. Brown is a good color for coffee shops, green for health food. The color of orange juice can alter how sweet it seems. Wine tastes better under red lighting and so on. All of this fit into his perfectly rational world. The idea that the colors of the alebrijes had some subtle impact on the emotions was not simply mystical mumbo jumbo.

Paul thought mathematics was the path to truth when he was young but he got blindsided by fractals and matrices and complex analysis, by Godel and Cantor. He gravitated to physics but quantum theory upended his hope for some ultimate truth. Peace, peace, there was no peace.

The idea that he had a nahual seemed preposterous but he did feel that an irresolvable mystery underlies nature. Language is a metaphor. Thought is a metaphor. How then do we get a handle on truth? Astonishment, wonder, and creativity, intuition, feeling, and emotion. Is man more than mere flesh and blood? Paul hit the wall when he pondered these questions. We are a peculiar combination of dead atoms that form into a body and awake into life. How crazy is that?

“Paul, come inside,” said Edith. “You’re lost in one of your dreams again. It’s time for lunch.”

“On my way,” said Paul. “Sorry. Just listening to the birds.”

“Be careful you don’t end up like that monk who got tangled up in a birdsong and lost fifty years,” laughed Edith.

Paul ignored her. “They’re all coming out again as it begins to warm up.”

“Yes,” said Edith. “The osprey are back again. That family has been here as long as we have. Forty years! I wonder how many generations that makes?”

“At least four or five I would think,” said Paul. He put his arms around her waist then reached past her to the stovetop to pick out a snow pea from the vegetables in the skillet.

“Don’t you dare!” she laughed. “We’re sitting at the table like civilized people. We’re not barbarians. You carry the fish and the wine. I’ll bring the vegetables after I plate them.”

They ate outside on the deck. A flock of wild turkeys sauntered by on the field below them searching for worms and insects. After lunch, over a glass of wine, Paul decided to tell Edith what he’d been thinking about.

“I’ve been searching for my nahual,” said Paul. He laughed uncomfortably.

Edith looked at him with her aquamarine eyes. He loved those eyes. Sometimes they faded to an aquamarine grey as they did now. A sign that it was okay for him to move ahead.

“You don’t really believe in all that, do you?” said Edith.

“Of course not,” said Paul. “I don’t believe in protector animals or animal companions any more than guardian angels or Philip Pullman’s daemons. Actually, it should be the other way around, right? We should protect the animals. They’re the ones in danger as our generation plunders the planet.”

“Absolutely! The ravens destroy my garden, the deer eat my flowers, the foxes kill our chickens, and the bears grow bolder and bolder. It’s all because we’re taking over their natural habitat. What’s going to be left for our grandkids if we keep this up?”

Something happened out in the meadow as they spoke. Animals appeared. Paul sensed them but didn’t see them at first. Edith was totally unaware. A bear, a deer, a mountain lion. An osprey perched high on a pine tree, a raven on a redwood limb, a woodpecker at the top of a limbless snag. A goldfinch tucked into a huckleberry bush. A robin pecked the grass, a quail took refuge under a rhododendron. A possum, a raccoon, some wild turkeys. An owl on a fir tree, a bat in the hollow of a Tanoak. A dragonfly, a butterfly, a golden moth.

“We can learn … from nature,” said Paul. His speech slowed as his mind wandered. “All of it … rationally … emotionally … Something has got … into my brain Edith … from Mexico … something to do with the alebrijes. There’s … an order … to … the universe … if … I could only … understand it. The problem … is … my brain. … is this … chaotic mess.”

Edith was concerned. Paul didn’t seem right.

“So,” asked Edith hoping to comfort him, “did you find your nahual?”

“Well,” said Paul, “I’ve been dreaming of … a jackrabbit … that leads me … around.” He didn’t want to say he had a vision. But it was a vision. He was not asleep.

“That’s good,” said Edith. “I’ve seen a lonely jackrabbit around here since we got back. Maybe he’s looking for you? But if your alter ego is a jackrabbit, I don’t understand why with those big ears you can’t hear me when I speak to you.” She laughed. Paul liked her laugh.

“That’s not how it works,” said Paul. “You don’t … necessarily … take on the characteristics of your nahual … Anyway … I read … that … if I don’t like my nahual … I can choose … something else.”

“Really? That sounds … I don’t know … like the whole idea is just some stupid fantasy. It is, you know, nothing but prehistoric myth.”

“The idea … is … to get you started … on a journey … I suppose … most people accept … whatever they’re given … It’s okay to choose something different … but whatever … you choose… it has to agree.”

“Agree?” said Edith. “How do you know if it agrees?”

Paul stopped to look at a raven fly overhead. Neither of them saw the animals in the meadow. Paul’s sensations however grew stronger. He smelled something wild and musty.

“I guess … it’s … a connection … you feel over time … in dreams … thoughts … meditation … encounters … whatever.”

“I think it’s silly,” said Edith, “a waste of time.”

“I … used to think so too … but not anymore … I don’t … know what I think … Nature … it isn’t just material … I … don’t like the word spiritual … but I feel strongly there is something else … I can’t … figure it out.”

“Oh boy,” exclaimed Edith. “Another one of your crazy ideas I’ve got to deal with. Are you okay? You sound off.”

“I feel … strange … inside my head …” said Paul. “I want … it’s not … you know … terrible … to think … to think how best to live life. Maybe … maybe it’s … the most important thing.”

“The best way to live your life is to live it,” said Edith.

“Not according to Socrates,” said Paul.

“There you go again with the philosophers,” said Edith. “I’m sick of philosophy, sick of it. You’re no jackrabbit. You’re a stubborn old mule!”

Edith went inside to get another glass of wine.

Paul’s eyes glazed into a stare. He lost his balance. The world turned upside down.

“My God! … Out in the meadow! … Look! … They’re coming!” Paul was terrified. There were animals that didn’t belong there—monkeys, storks, bulls, iguanas, crabs, giant spiders, an armadillo. Dragons and strange insects.

“Oh that,” said Edith. “It’s just the alebrijes. They wander from time to time. I guess I didn’t tell you because I assumed you knew.”

Paul was astounded. “ You mean … they awaken?”

“What? You thought they just sat silently on the shelves inside the house?” laughed Edith.

Paul didn’t know what to think. Was Edith crazy? Was he crazy? Was he in some crazy dream? He felt something tickling his legs. He looked down. A snake had wound around him. It looked up. Their eyes met and the snake spoke.

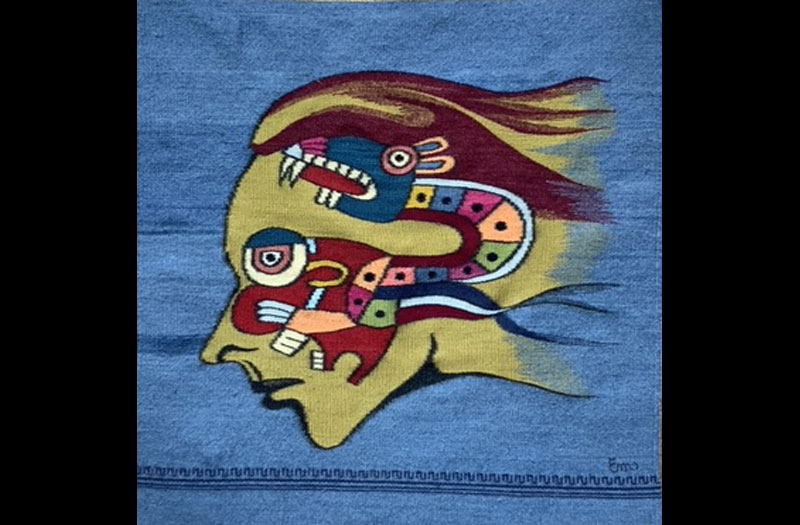

“I am Coatl, your nahual. I’ve been chasing that damn jackrabbit it seems like forever. Normally I wouldn’t bother you but you are so fucking dense you don’t seem to know I’m in your head. I need that jackrabbit Paul. He’s got the answers but he’s always running away from me.”

The snake tightened its grip on Paul’s legs. “Help me, Paul, and I’ll help you.”

‘What’s going on,” said Paul. “I don’t understand. And how did you get here. We don’t have snakes. Well, except for garden snakes but you’re no garden snake.”

“No, I’m not,” said the snake. “I’m the great great great great great great great and so on grandson of Quetazalcoatl, the feathered serpent, the creator god, the god who’s as fast as the wind, but I can’t catch that damned jackrabbit.”

“Well, I’ve not been able to catch it either,” said Paul. “Could you loosen your grip on my legs a bit? They’re starting to go to sleep.”

“Sure thing,” said Coatl, “but first I’m gonna tell you a little story. You like stories, right?”

“Go ahead,” said Paul, “if you must.”

“Okay,” said Coatl. “Here goes.”

Back in the day of my great and so on grandfather Quetzalcoatl, Mayahuel was the goddess of the agave plant and of fertility. Agave is used to make mezcal, a delicious smoky liquor produced all over Mexico especially in Oaxaca where your alebrijes come from.

“I know what mezcal is,” said Paul.

Aguamiel is the sap of the maguey plant. Since grandfather’s time we’ve used it for medicinal purposes. Fermented, the sap makes a beer-like beverage we call pulque that can give you a psychedelic high. Later we learned to distill the sap to make the mezcal you like so much..

As the story goes, Mayahuel lived hidden away in a far corner of the universe as the prisoner of her evil grandmother Tzitzímitl. Tzitzímitl loved to eat human hearts. The Aztecs were fascinated with blood and gore you know. They believed that during a solar eclipse when the moon swallowed the sun, Tzitzímitl would swoop down to earth to devour all the hearts of humanity, a sort of Last Judgment for heathens.

I’m a little murky on this next point. A good god from the earth went up to heaven to destroy the evil Tzitzímitl. Some say this was Patecatl, the pulque god. Others say it was Ehecatl, the serpent god, while still others say it was Quetzalcoatl, the god of wind and learning. I’m gonna tell you right here, it was Quetzalcoatl. The other two gods couldn’t hold a candle to my great and so on grandfather. When Quetzalcoatl arrived in heaven he found the beautiful Mayahuel who had four hundred breasts. He was immediately smitten.

Quetzalcoatl acted just like you’d expect. He whisked Mayahuel down to earth and impregnated her. Not exactly the Immaculate Conception, but the result was similar. The brood became the Centzon Totochtin known as the 400 rabbits. I think the movie Gremlins was based on the Centzon Totochtin but I’m not sure about that. I’m only a snake.

Tzitzímitl got her revenge. She chopped Mayahuel into small pieces and scattered them throughout Mexico, mostly in Oaxaca. All these pieces of Mayahuel became the maguey plant and the maguey plant became mezcal. The 400 rabbits nursed on the 400 breasts. The rest is history. To this day these divine rabbits travel throughout Mexico. They show up at parties and gatherings and deliver the gift of drunkenness to the people. Each rabbit represents a different way a person can experience intoxication. I think the Christians call this communion but I’m not sure. I’m just a snake.

So, if you catch that jackrabbit for me, I’ll slip out of your head. You can go back to that place you call reality and I will go rattle someone else’s cage. Otherwise, it’s turtles all the way down.

“Paul! Paul! Wake up!”

Edith was frantic. Paul was lying on the deck out cold.

“Wake up honey! Wake up!”

Paul slowly came to. He was groggy and his head hurt.

“I sl … slipped on that damn loose stair and fell,” said Paul. “My head hurts.”

“You were out cold,” said Edith. “Maybe I should take you to the doctor.”

“I’m fine,” said Paul after he regained his bearings. “Maybe a shot of mezcal. You know what they say, para todo mal, mezcal; para todo bien también.”

“I’m glad to see your sense of humor’s back. Before I went inside you were lecturing me on Socrates and waxing on about your nahual. What is it anyway? Did that bump on the head help you sort it all out?”

Paul looked at the door to the house. He saw two pillars in the form of snakes with serpents fangs. He blinked and they disappeared.

“My nahual?” said Paul. “It’s a snake named Coatl but I reject it. You hear that! I reject it it. I need a mezcal. Can you get me a glass? I’m still a little wobbly on my feet.”

Edith went into the house to get Paul his mezcal shaking her head. A snake? The man’s gone off his rocker.

Paul looked down at his feet. “Fuck off!” he shouted. He turned toward the meadow. There were no animals, just the tops of the weeds blowing in the wind. He heard a pop as Edith pulled the cork out of the mezcal bottle. He heard the gurgle of the mezcal as she poured it into the glass. A jackrabbit sat up in the weeds, it’s ears pointing to the blue sky above. Then it was gone. He heard a scuffle and a squeak.