I met Jean in 1987. She had a fascinating family history. Her late husband, Thomas Nast St. Hill, was the grandson of the famous caricaturist and political cartoonist Thomas Nast. Nast was the creator of our modern version of Santa Claus. He also created the elephant and donkey symbols for the two political parties. Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving Dinner, a cartoon published by Nast on November 20, 1869, celebrates the ethnic diversity and envisions the political equality of citizens of the American republic, something we might want to think about again today.

While her husband’s famous grandfather is a story of enduring interest, my story is about Jean, who taught her novice financial planner an important lesson.

Jean was 85 when we first met. She often arrived in my office with her dogs just after or just before taking them for a walk on the Mendocino headlands. On Monday morning, October 19th, Jean walked into my office with a thick bundle of stock certificates. Her attorney had advised her to set up a trust and the purpose of her visit was to transfer ownership of her stocks to the trust.

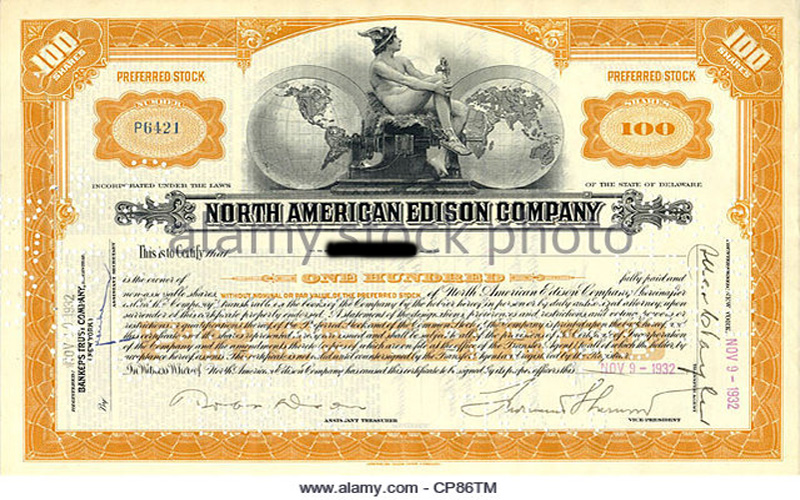

Jean had an old-time attitude with regard to her investments. She insisted on holding all the certificates in her safe deposit box in her bank. She didn’t trust a brokerage company in some distant city to hold them for her account even though she had been told it was just as safe and easier if she wanted to make any changes.

The process of changing the title on stock certificates is more difficult than it might seem. There are two choices. The certificates can be sent with instructions to a transfer agent who will enter the information in the corporate books and issue new certificates properly registered to the client. To avoid having to send out certificates to multiple transfer agents, we agreed it would be easier to set up two brokerage accounts, one for Jean and one for her trust. We would send the certificates into her personal account, instruct the brokerage company to transfer them to the trust account, and then reissue new certificates in the name of the trust to be sent back to her. It took some explaining but Jean agreed this sounded like a good plan. For each certificate we had to prepare and sign a stock power, issue a receipt, and make multiple copies. Given that she had dozens of certificates, this took some time as you can imagine.

For those of you who don’t remember (or were not alive at the time), in the 1980s the only desktop computers available were the clunky MS-DOS computers with their phosphor screens. In my case the characters were bright green on dark green. The script took a few seconds to appear and fade out like ghosts dancing across the screen. The operator had to type in commands at the command prompt to get the computer to do anything. It was SLOW going.

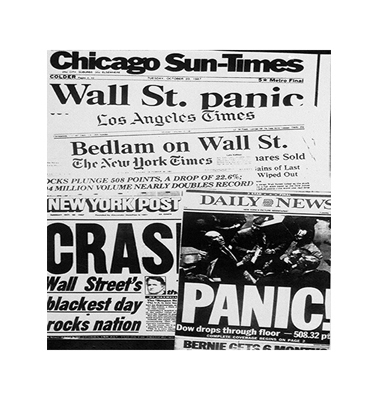

As I sat with Jean facing me from the other side of the desk methodically processing her thick pile of stock certificates, I periodically typed in commands to access the behavior of the stock market. Stocks had been unusually volatile since reaching a high point in August. On the Friday before the Monday that Jean had her appointment, the Dow Industrials stock average declined nearly 5%. Many investors, including myself, were nervous. What I saw on the screen was nothing less than horrifying.

The Dow was down 100 points, about four and a half percent. But that was nothing. The next time I looked the Dow was down 200 points.

Jean noticed my anxiety.

“It’s a bad day, isn’t it?”

“It sure is, Jean. It sure is.”

I tried to act reassuring but the Dow was now down 300 points. I had a hard time even speaking as my throat and mouth dried up. But, I continued slowly processing the certificates one by one.

In the middle of it all, a wide-eyed young man with wild hair came charging into the office. His eyes were full of panic.

“Do you sell gold?” The words all running together were barely intelligible. He sounded desperate.

“No, I’m sorry. I don’t sell gold.”

“I want to sell everything and buy gold. Got to go.” It was the first and last time I saw him, rather strange in a small town.

I looked at the screen and the Dow was down 400 points, nearly 20%. Twenty-percent in ONE DAY.

Napkin Art, Sea Gull Cellarbar, World in Flux, unsigned

“David,” said Jean so softly I almost didn’t hear.

“David, listen to me. Look, look at these certificates. Look at the dates. Look at this one, 1928, or this one, 1932. Tom and I owned these before the Depression. When the Depression came, we held on. They paid dividends, every year. They split and split again. Kept on paying dividends. There have been times when the price went down but we just held on and took the dividends. Stocks fluctuate. Don’t worry.”

Easy for her to say, I thought.

“I see the look in your eyes, David. Believe me, the world is not coming to an end today. These companies are not all going broke. They may be going down, but not broke. Thank you for your work. Now, send these in and make sure I get my new certificates back. I hate being without them. It’s time to take my dogs for a walk. Tomorrow will be a better day, or the day after.”

She walked out of the office smiling, her dogs on a leash. I saw her out the window a few minutes later walking on the headlands. Jean was my client for another ten years. I went to her ninetieth birthday party in Little River. What do you take to a ninety-year-old woman who still owns the stocks she bought before Hoover was President? I took an illustrated copy of Lao Tzu’s The Way of Life. She didn’t need it, but I think she liked it.

The year was 1987, my first full year as a financial adviser. On that Monday that Jean sat in my office, the Dow Jones Industrial stock average suffered what was and still is the largest one day percentage decline in its history, over 22%. For many, including myself, it was terrifying. Some who sold into the panic never recovered.

What Jean taught me was the importance of patience. Had you invested in August of 1987 at the peak of the market and held on until today, your annualized return including dividends would have been 9.5%. Had you been brave enough to invest just after that 22% crash, your average return would have been 10.2%. If you had taken out your dividends every year, your investment would have still increased at an average annual rate of 7%. Jean knew what could happen from her own experience during the Depression. Will patience pay off when we have the next stock market crash? No one knows for sure.

The future laughs at the past as it surveys the course of destiny groping its way in the dark.

Jean’s husband was the author of the following

http://www.americanheritage.com/content/life-and-death-thomas-nast?page=show

be sure to pay particular attention to the parts about the investments Thomas Nast made.

I am humbled and honored by your response. The link you sent is wonderful and I’ll pass it along. I loved Jean dearly and admired her wonderful family. Many thanks, David