[Click on BLUE links for sources and information]

Christianity, if false, is of no importance, and if true, of infinite importance. The only thing it cannot be is moderately important. C.S. Lewis

If he was not God, he was no realist, only a liar, and the crucifixion an act of justice. Flannery O’Connor

Be bold, be bold but not too bold. Isak Dinesen

In the mid-1960s a few years before I arrived in Mendocino when Martin and Marlene Hall owned The Sea Gull, there was a man, a loner, named Kent Chapman who frequented the Sea Gull Coffee Shop. According to Marlene:

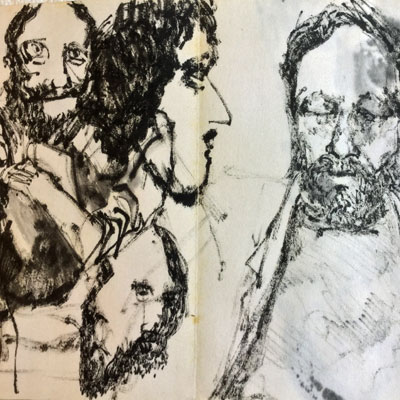

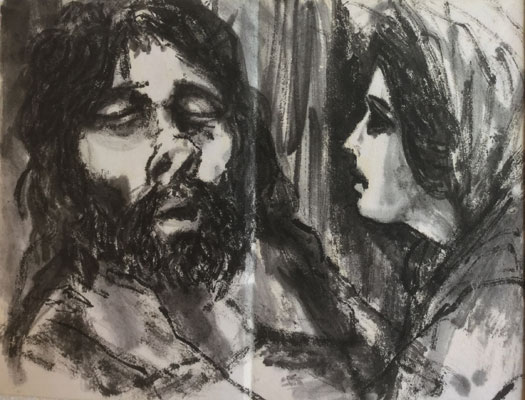

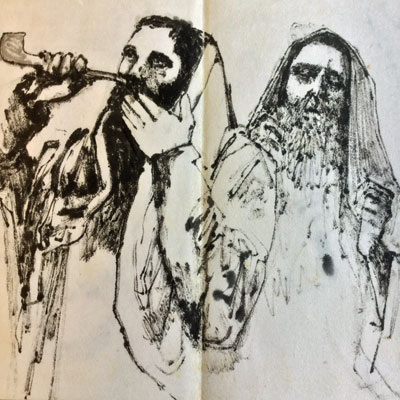

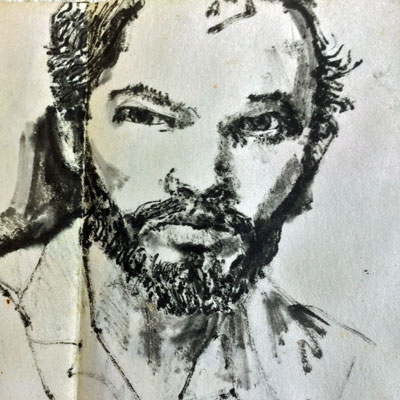

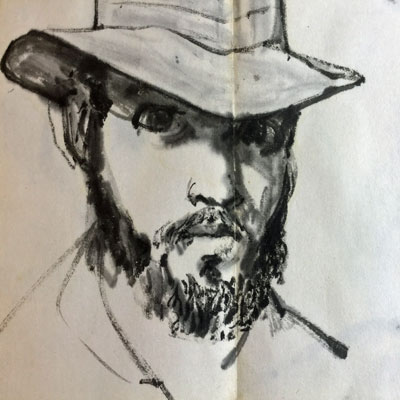

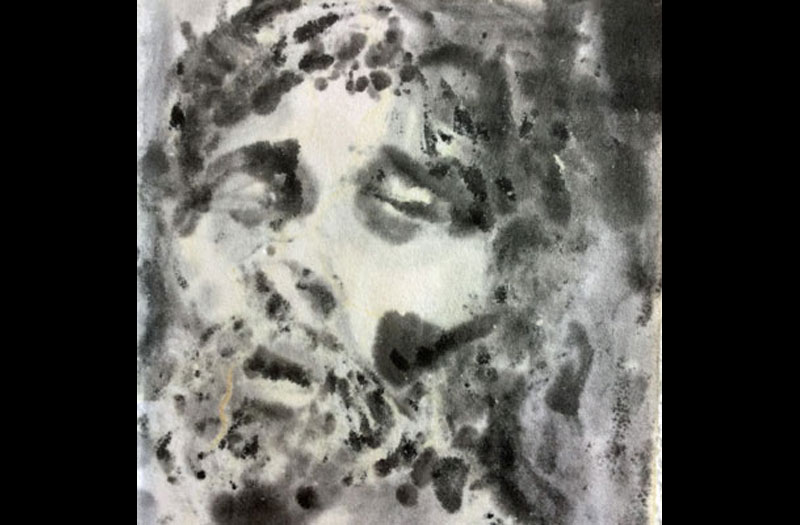

He was one of our “orphans”; we even had him housesit our house once when we went away. No idea when he disappeared [from Mendocino]. Not a clue, no word from him since the mid-sixties. He sat for hours at the Seagull drawing and I have a small book of his charcoal work. Marlene Hall

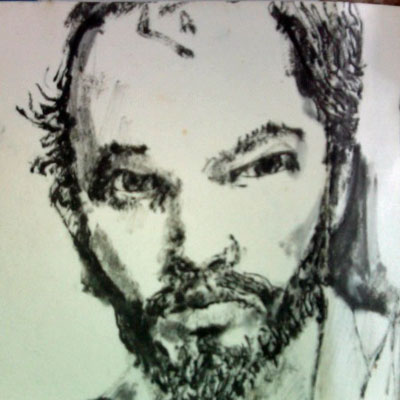

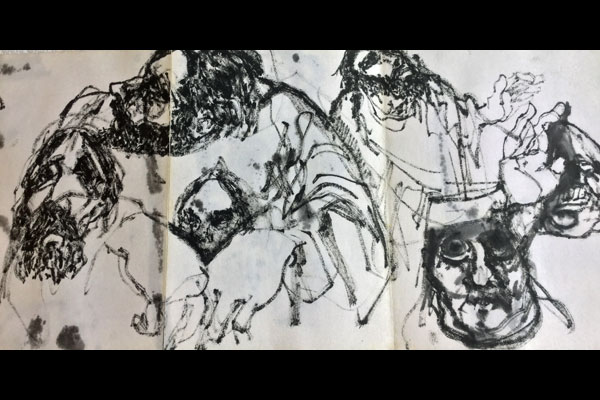

Charcoal sketch, Kent Chapman, self portrait

During this Christian holy week it may seem odd to bring up Kent Chapman but his charcoal drawings (which Marlene kindly gave to me) are all religious in nature and as she pointed out “all concerned with Judaism.” That Jesus, a renegade Jew, was the spiritual center of a religion, Christianity, practiced primarily by Gentiles has always seemed a little strange to me especially given the ongoing arguments between the two religions. But I am no expert. Never the less, Kent Chapman’s charcoal sketches from all those years ago aroused in me an interest in the Jesus story—in particular how the story remains a relevant subject in the modern literary world. That it needn’t have been this way is the point of a story on Pontus Pilate by Anatole France:

I learned by chance that she had attached herself to a small company of men and women who were followers of a young Galilean thaumaturgist. His name was Jesus; he came from Nazareth, and he was crucified for some crime, I don‟t quite know what. Pontius, do you remember anything about the man?”

Pontius Pilate contracted his brows, and his hand rose to his forehead in the attitude of one who probes the deeps of memory. Then after a silence of some seconds: “Jesus?” he murmured, “Jesus—of Nazareth? I cannot call him to mind.” Anatole France, the Procurator of Judaea

Easter, for obvious reasons, is a time when various Jesus stories and tributes and religious ceremonies occur nonstop for several days. The whole spectacle is nearly impossible to miss. There are TV specials, movies, news articles, and sometimes new books. For this reason I have embarked on a separate but parallel path—an attempt to read a few stories and novels that share the subject but not the devotional aspects of Easter week. Below is a list and some short comments to choose from if you are so inclined. In juxtaposition to C. S. Lewis, I do not think that truth or falsity is the point of the Jesus stories or that one must be a believer to ponder the meaning of life, etc.

I am saying this because it is desirable in all things to preserve moderation and an even mind.

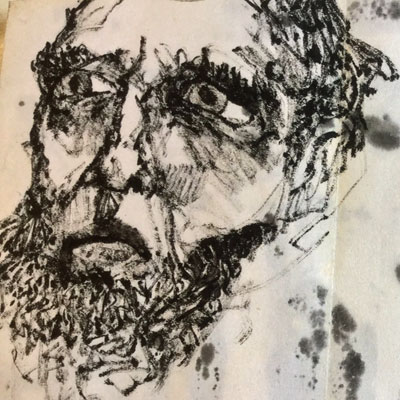

Charcoal sketch, Kent Chapman

In this I most certainly diverge from God’s words in Revelation 3:15-17:

I know your works, that you are neither cold nor hot. I wish that you were cold or hot. So, because you are lukewarm, and neither hot nor cold, I am going to vomit you out of My mouth. Because you say, “I’m rich; I have become wealthy, and need nothing,” and you don’t know that you are wretched, pitiful, poor, blind, and naked.

I diverge also from someone I more often identify with, the philosopher Walter Kaufmann.

If you must pour new wine into old skins, you should at least follow one of Jesus’ other counsels and let your Yes be Yes, and your No, No.

When I don’t know, I’m not afraid to admit it. Indecisiveness is better than fanaticism when the truth is in question. Honest doubt denies me the passion of the zealot. This sometimes works in my favor, sometimes against it. I try to follow the words of Richard Feynman:

Through all ages men have tried to fathom the meaning of life. They have realized that if some direction or meaning could be given to our actions, great human forces would be unleashed. So, very many answers must have been given to the question of the meaning of it all. But they have been of all different sorts, and the proponents of one answer have looked with horror at the actions of the believers in another. Horror, because from a disagreeing point of view all the great potentialities of the race were being channeled into a false and confining blind alley. In fact, it is from the history of the enormous monstrosities created by false belief that philosophers have realized the apparently infinite and wondrous capacities of human beings. The dream is to find the open channel. What, then, is the meaning of it all? What can we say to dispel the mystery of existence? If we take everything into account, not only what the ancients knew, but all of what we know today that they didn’t know, then I think that we must frankly admit that we do not know. But, in admitting this, we have probably found the open channel.

Charcoal sketch, Kent Chapman

Jesus means something to our world because a mighty spiritual force streams forth from him and flows through our being also. This fact can neither be shaken nor confirmed by any historical discovery. It is the solid foundation of Christianity. Albert Schweitzer, The Quest of the Historical Jesus

Whether or not Jesus was a real historical person has never been satisfactorily resolved. The philosopher/theologian Albert Schweitzer concluded the odds are in favor: “ … we must conclude that the supposition that Jesus did exist is exceedingly likely, whereas its converse is exceedingly unlikely.” The Biblical scholar James Tabor describes Schweitzer’s view that it is not the historical Jesus but the spiritual Jesus that matters.

In Schweitzer’s final and most important chapter he argues that the union of what he calls “thoroughgoing skepticism” and “thoroughgoing eschatology” represents an impassible and enduring obstacle to traditional Christian theology. Jesus, according to Schweitzer, “lays hold of the wheel of the world to set it moving on that last revolution which is to bring all ordinary history to a close. It refuses to turn, and he throws himself on it. Then it does turn; and crushes him” (p. 370-71). And yet, even with this perspective, this “negative theology” as Schweitzer calls it of a “failed messiah,” he leaves the reader with his final chapter that he calls “Results.” He writes that “Jesus means something to our world because a mighty spiritual force streams forth from him and flows through our time also,” and “…it is not Jesus as historically known, but Jesus as spiritually arisen within men, who is significant for our time and can help it. Not the historical Jesus, but the spirit which goes forth from him and in the spirits of men strives for new influence and rule, is that which overcomes the world.” (pp. 399, 401).

Believing it is likely that Jesus actually existed is a far cry from proving that he is God or that he was resurrected. These may be matters of faith for some, for many, but faith is not sufficient to convince all reasonable people, even those sympathetic to the cause such as Schweitzer.

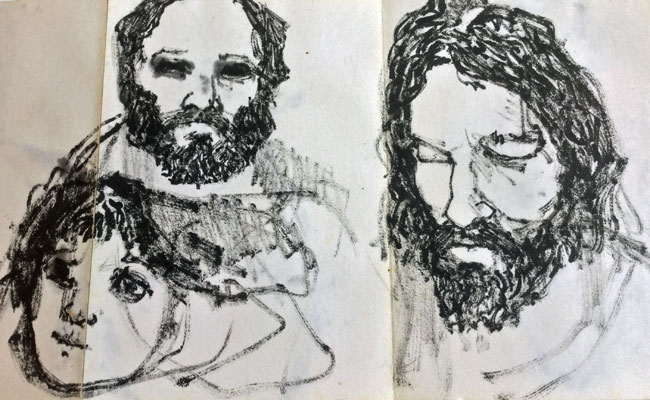

Charcoal sketch, Kent Chapman

And if Christ be not risen, then is our preaching in vain, and your faith is also vain. 1 Corinthians 15:14

I was raised a Catholic but at a young age I began to have my doubts and eventually left not only the church but all organized religion. While I occasionally go through my periods of strident atheism, I have tried to stop with the preaching, to accept others beliefs when they do not interfere with my life or the lives of those who believe differently. I sometimes fail. But, I do my best to adhere to the words of the philosopher Walter Kaufmann:

I do not believe in any after life any more than the prophets did, but I don’t mind living in a world in which people have different beliefs. Diversity helps to prevent stagnation and smugness; and a teacher should acquaint his students with diversity and prize careful criticism far above agreement. His noblest duty is to lead others to think for themselves. Walter Kaufmann, The Faith of a Heretic

Charcoal sketch, Kent Chapman

Flannery O’Connor is a writer I greatly respect and admire in spite of my inability to accept her faith. Hers was a Christian faith she took seriously. Moderation was not her cup of tea.

Unlike the majority of Catholics the Fitzgeralds had known, O’Connor lived her faith. In a memoir about her, Robert Fitzgerald wrote admiringly of her inability to speak in abstractions: “She could make things fiercely plain. As in her comment, now legendary, on an interesting discussion of the Eucharist Symbol: ‘If it’s a symbol, to hell with it.’ “. New Yorker, Hilton Als, January 29, 2001

I am no disbeliever in spiritual purpose and no vague believer. I see from the standpoint of Christian orthodoxy. This means that for me the meaning of life is centered in our redemption by Christ and what I see in the world I see in its relation to that. Flannery O’Connor

Charcoal sketch, Kent Chapman

Flannery O’Connor’s vision of Jesus (especially in her novel Wise Blood) sticks in the mind like an earworm. The earworm, according to my late friend Hanley Norins, works well in advertising, a truth not lost on the purveyors of organized religion. This image of Jesus O’Connor gives us in Wise Blood has burrowed deeply into the psyche of many of today’s writers regardless of their personal beliefs.

Later he saw Jesus move from tree to tree in the back of his mind, a wild ragged figure motioning him to turn around and come off into the dark where he might be walking on the water and not know it and then suddenly know it and drown. Hazel Motes in Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood

O’Connor’s novels and short stories are, like her ancestral South, “Christ haunted” but not “Christ centred.” Her great talent was to write stories about real people who lead believable if sometimes bizarre lives. Some of her work, if not centered on Christ, certainly puts Christ everywhere around the borders. And that’s the sort of God she seemed to like best, moving from tree to tree, not so obvious but inescapable. If, during this week, you want to read something of the real Jesus without the pablum, try Flannery O’Connor. I especially like the novel Wise Blood and her short story A Good Man is Hard to Find.

Charcoal sketch, Kent Chapman

If you need a primer on the New Testament, you might take a look at Philip Pullman’s The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ. Pullman wrote the popular Dark Materials trilogy of which the first volume, The Golden Compass, was made into a movie. In The Good Man Jesus, Pullman explores the possibility that Jesus had a twin brother, Christ. He works many of the most famous Jesus parables into his novel. Pullman clearly likes the Jesus character and dislikes the scoundrel Christ. Spoiler alert: Christ is a stand-in for Judas. He betrays his brother and conspires with the Church to control the growth and spread of Christianity. Pullman is antagonistic toward organized religion and expounds on the hypocritical nature of many Christians (consider the political right today). To make the point, he retells Matthew 23 in effective plain language.

Charcoal sketch, Kent Chapman

‘They teach with the authority of Moses, don’t they? And you know what the law of Moses says? Listen to what the scribes and the Pharisees say, and if they agree with the law of Moses, obey them. But do as they say – don’t do as they do. ‘Because they’re hypocrites, every one of them. Look at the way they vaunt themselves up! They love to sit in the place of honour at a banquet, they love to sit in prominent positions in the synagogue, they love to be greeted with respectful words in the marketplace. They preen themselves on the correctness of their costume, while exaggerating every detail to draw attention to their piety. They encourage superstition and they ignore genuine faith, while all the time they’re fawning over prominent citizens and boasting of the importance of their powerful friends. Haven’t I told you many times how wrong it is to think that the higher you are among men, the closer you are to God? ‘You scribes and Pharisees, if you’re listening – be damned to you. You take endless scruples over the tiniest matters of the law, while you let the great things like justice and mercy and faith go unnoticed and forgotten. You strain the gnats out of your wine, but you ignore the camel standing in it. ‘Damn the lot of you – hypocrites that you are. You preach modesty and abstinence, while indulging in the costliest luxuries; you’re like a man who offers his guests wine from a golden cup, having polished the outside while neglecting the inside, so it’s full of dirt and slime. ‘Damn you each and every one. You’re like a tomb covered in whitewash, a handsome structure, gleaming and spotless – but what’s on the inside? Bones and rags and all kinds of filth. ‘You snakes, you brood of vipers! You’ve persecuted the best and the most innocent, you’ve hounded the wisest and the most righteous to death. How in the world do you think you’re going to escape being sent to hell?

How damning that is for today’s political right? I can’t help making this observation which is so obvious especially after the long awaited Mueller report has been released. Go to this link to see why I feel like yelling at the top of lungs just like the Jesus of the Bible: “You snakes, you brood of vipers! [I apologize for this lapse in my moderation but I still have the ability to get worked up at times.]

An interesting and radical retelling of the Resurrection was penned by the famous D.H. Lawrence in The Man Who Died (or The Escaped Cock as he would have preferred). It was the last novel he wrote before he died. It consists of two short chapters. Rather than ruin the book with any summation, I will let Lawrence describe it in his own words:

I wrote a story of the Resurrection, where Jesus gets up and feels very sick about everything, and can’t stand the old crowd any more – so cuts out – and as he heals up, he begins to find what an astonishing place the phenomenal world is, far more marvellous than any salvation or heaven – and thanks his stars he needn’t have a ‘mission’ any more.

Charcoal sketch, Kent Chapman

Many reasonable people including some theologians have trouble with some of the more fantastic stories in the bible. Consider Karl Jaspers:

[The theologian Rudolf Bultmann] says of Jaspers: “He is as convinced as I am that a corpse cannot come back to life and rise from his tomb … What, then, am I to do as a pastor, preaching or teaching, I must explain texts … ? Or when, as a scientific theologian, I must give guidance to pastors with my interpretation?” quoted from The Faith of a Heretic book by Walter Kaufmann

An interesting Jewish adaptation of the Jesus story is The Liar’s Gospel by Naomi Alderman. Alderman’s novel tells the story from four points of view (like the four most famous Gospels) but different points of view than those of Mark, Matthew, Luke and John. The four versions in Alderman are those of Mary (Miryam), Judas (Iehuda), Caiaphas and Barrabas (Bar-Avo). The book is a mix of history, fantasy and genuine imagination. It is a new and original story. That plus some good writing drew me in.

I have not read Testament of Mary by Colm Tóibín. It is on my list for Easter weekend. It tells the story of Jesus’ mother from whom we hear very little in the New Testament.

Charcoal sketch, Kent Chapman

The last two books I will mention are by Nobel laureate J.M. Coetzee, The Childhood of Jesus and the Schooling of Jesus. These books are mysterious. They are odd speculations on parts of Jesus’ life for which we have little data to draw on from the Gospels. It is not entirely clear who is who. The principal characters are a six/seven year-old child Davíd, his caretaker (not formally adopted father) Simón, the cold beautiful Ana Magdalena, the shady Dmitri seemingly borrowed from Dostoevsky, and the sexless opinionated mother by lottery Inés. Some think Davíd, the child, is Jesus. Others think the “growing up” and “schooling” is actually done by Simón. The two books take place in the strange mythical socialist-like countries of Novilla and Estrella. One loses all memory of the past when they arrive there. There is an atmosphere rather like Comala in Pedro Páramo by Juan Rulfo, but these are not ghost towns. There is plenty of action including sex and murder and some droll humor like when Simón and Inés drive into the country to pick up Davíd and find themselves on a nude beach.

‘I am looking for the place where school groups go,’ he says to the girl behind the counter.

‘El centro recreativo. Follow the road along the lake front. It is about a kilometre further on.’

El centro recreativo is a low, sprawling building giving onto a sandy beach. Disporting themselves on the beach are scores of people, men and women, adults and children, all in the nude.

… ‘Dmitri said nothing about this – this nudism,’ he says to Inés.

‘What shall we do?’

‘Well, I am certainly not taking off my clothes,’ she replies. Inés is a good-looking woman. She has no reason to be ashamed of her body. What she does not say is: I am not taking off my clothes in front of you.

‘Then let me be the one,’ he says.

While the dog, set free, lopes off toward the beach, he retires to the back seat and divests himself of his clothes. Picking his way delicately over the stones, he arrives on the sandy beach just as a boat full of children comes in. A young man with a sweep of dark hair like a raven’s wing holds it steady while the children tumble out, splashing in the shallow water, whooping and laughing, naked, Davíd among them. With a start the boy recognizes him. ‘Simón!’ he calls out, and comes running. ‘Guess what we saw, Simón! We saw an eel, and it was eating a baby eel, the baby eel’s head was sticking out of the big eel’s mouth, it was so funny, you should have seen it! And we saw fishes, lots of fishes. And we saw crabs. That’s all. Where is Inés?’

‘Inés is waiting in the car. She isn’t feeling well, she has a headache. We came to find out what your plans are. Do you want to come home with us or do you want to stay?’

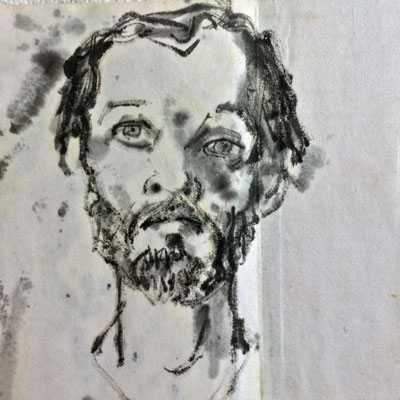

Charcoal sketch, Kent Chapman, self portrait

This is not meant to be a book review and I will not go into more detail other than to say that I very much enjoyed both of Coetzee’s books even if I don’t understand them. That is why I intend to read them at least one more time. There is one poignant scene I will mention because it seems very much like a resurrection story. A boy, Bengi, is playing with David. They see some ducks in a pond. Bengi throws a rock and hits a duck breaking its wing. A young man catches the duck and puts it out of its misery. Bengi is instructed to bury the duck. Then we have this discussion between Davíd and Inés.

‘He didn’t bury him. He just threw him in the bushes.’

‘I’m sorry about that, but the duck is dead. We can’t bring him back. You and I will go and bury him as soon as the day’s work is over.’

‘I wanted to kiss him but Bengi wouldn’t let me. He said he was dirty. But I kissed him anyway. I went into the bushes and kissed him.’

‘That’s good, I’m glad to hear it. It will mean a lot to him to know that someone loved him and kissed him after he died. It will also mean a lot to him to know he had a proper burial.’

‘You can bury him. I don’t want to bury him.’

‘Very well, I will do so. And if we come back tomorrow morning and the grave is empty and the whole duck family is swimming in the dam, father and mother and babies, with no one missing, then we will know that kissing works, that kissing can raise one from the dead. But if we don’t see him, if we don’t see the duck family –’

‘I don’t want them to come back. If they come back Bengi will just throw stones at them again. He is not sorry. He is just pretending. I know he is pretending but you won’t believe me. You never believe me.’

Is Coetzee saying that resurrection is pointless because “Bengi will just throw stones at them again.”? I don’t know but it certainly seems like it to me.

In a 1992 interview Coetzee said: “Writing is not free expression. There is a true sense in which writing is dialogic: a matter of awakening the counter-voices in oneself and embarking upon speech with them. It is some measure of a writer’s seriousness whether he does evoke or invoke those countervoices in himself, that is, step down from the position of what Lacan calls ‘the subject supposed to know.’ ”

Could this (dialogic) be what Coetzee is doing in these two books ostensibly about Jesus? Should we all be awakening the counter-voices in ourselves and embarking upon speech with them?

I don’t know all the answers. I do sometimes hear voices arguing inside my head. I do not think they are either true nor false. But I do find them moderately important in sorting out the big questions that arise in life.

Enough. Read a few of these books/stories if you wish and sort out the answers for yourself. You might find they make your Easter more enjoyable. Then again, there’s always Jesus, Mezcal and the Easter Bunny or, if you are simply one of those folks who are so turned off to religion that even the mention of it makes your hair stand up, try these Easter Thoughts. And remember one important point about moderation, it applies to Easter feasts, Easter candy, and Easter eggs just as much as it applies to points of view.

“Africa, amongst the continents, will teach it to you: that God and the Devil are one, the majesty coeternal, not two uncreated but one uncreated, and the Natives neither confounded the persons nor divided the substance.” Isak Dinesen, Out of Africa

“… no one can be an atheist who does not know all things. Only God is an atheist. The devil is the greatest believer and he has his reasons.” Flannery O’Connor

Charcoal sketch, Kent Chapman, self portrait

The concept of Jesus being the “son” of some supreme supernatural all powerful being is simply stupid. the ONLY thing of importance of Jesus is his message(s) on how how to be a better human being…everything else is bullshit.

Religions…all of them…..screw things up and make people believe in silly things and divide us. Can’t we simply take the basic message of Jesus….use him a s role model? You know….be compassionate to others, be understand, be loving, be a good steward of your community and you’re planet, take care of your family…..damn…..these things are crucial. All of this crap about heaven and whatever is just total crap.

Right now we need need a hero…and the hero is US!