Frolicville is named after the shipwreck of a trading vessel that was headed to San Francisco from China. The crew got disoriented in the salt fog and crashed onto the rocks near Light House Point. There was no lighthouse in 1850, the year of the shipwreck. The only inhabitants in those days were the Pomo Indians.

The thing about Frolicville is you’re bound to see someone you know when the salt fog lifts. Today when the salt fog lifted I saw Parley B. Cause. Parley is a retired mathematician who sells and repairs shoes. He’s a specialist in the calculus of shoes and is integral to the wellbeing of the community. After all, everyone in town wears shoes except Cigarette Joe. Cigarette Joe walks around barefoot and bums cigarettes from the tourists in exchange for his folksy history of the massive salt sculpture of Father Time and the Maiden mounted atop the historic Masonic Lodge that’s now a bank.

“Hey Parley,” I yell out when I see him on the street as the fog etherealizes. “Can you fix these?” I hand him my favorite pair of Nunn Bush boots.

Parley pulls down his eyeglasses from the top of his Chicago Cubs baseball cap. “I can fix’em if I can differentiate’em,” he says. He inspects the cracked soles. “Yep,” he says, “these boys take rectangular hyperbolic soles, Gogol Cosplay I think. I’ll have to check.”

“Great, they’re my favorites,” I say. “I need them to climb up the ridge above Big River later today. Bring them by the Frolic Cafe when they’re ready.”

“Will do, Mac,” he says. “What’s up there, just dead souls is what I hear.”

“Some think a mob of unthinking humanity but I think the salt of the earth,” I say.

“Okay,” says Parley. “But it’s a long climb. That’s what I hear but I’ve never done it. Best remember that proverb, Mac, ‘a dead body’s only good to prop a fence with.”

“I’ll keep that in mind,” I say. Lost and lonely I think but not dead. We go our separate ways.

The weather turns a complete 180 as it’s prone to do around here. Sunny as a Fosters Freeze. I head to the Frolic Cafe where I wash dishes. First person I see when I walk through the back door is Dancing Water. She’s got the Coffee Shop today. Feather and Meadow are in the dining room.

I’m early so I order breakfast. I sit next to Flash at the coffee shop counter. Flash is one of the janitors.

“Two more tourists disappeared into the salt fog yesterday,” says Flash.

“I heard,” I say. “No matter how many warnings we give they just go ahead and do whatever they want.” Some of the volunteer fire guys look up from their bacon and eggs like goldfish and roll their eyes.

“That salt fog perambulates throughout our abode,” says Flash. “People come here to find the total zero they’ve been looking for all their lives, and because there’s no distractions, sometimes they find it and melt into it.”

Flash was a poet. And a philosopher. And a lover of classical music. There’s a harmony in music and poetry but philosophy is discordant. Still, I know what he means about people melting into the environment. I know more about the salt fog than anyone around here.

I finish my breakfast. I carry my dishes back to the dishwasher and start my shift. When the kitchen’s humming it sounds like a rickety machine, plates clanking, silverware clinking, the cooks and the waitresses yelling. The dishwasher has a pleasant hum or maybe I’m just used to it. I work a split shift today. Feather brings a tray of dirty dishes from the dining room. She’s Polish.

“Is there fog in Poland,” I ask.

“Oh, they turn the fog machine on now and again,” she says with a smirk. She must be talking about a different kind of fog.

Outside by the garbage bins I hear the geese going south but the salt fog obscures the view. A goose falls out of the sky all white in a tight fitting coat of salt. I carry the goose into the kitchen and give it to the cook.

My shift is about to end. Dancing Water comes back to me and says “the cobbler guy, Parley, is in the coffee shop. Says he has something for you.”

“Thanks,” I say. “Tell him I’ll be out in a minute.”

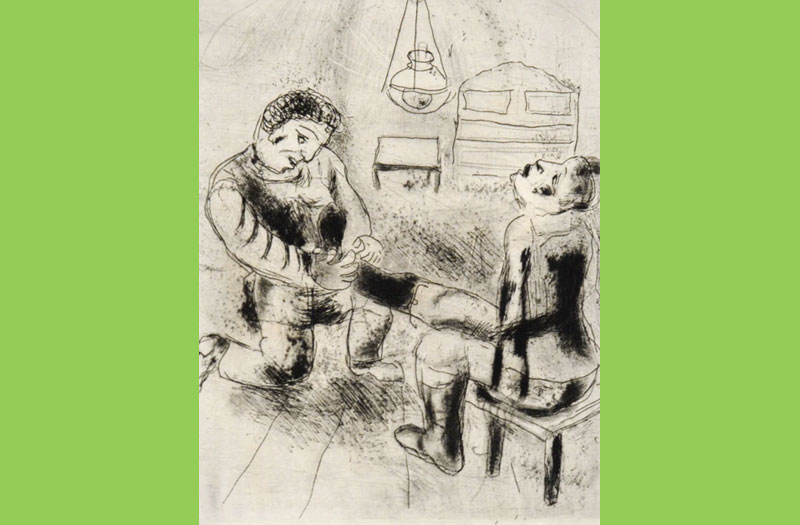

In the coffee shop, Parley has me sit on a stool while he puts my boots on. I think about the fog and I feel very human and exposed.

Salt fog encompasses the town. It creeps up Big River, slides up the trunks of giant redwood trees and reaches Statue Ridge where the lost tourists hang out in their statuesque salinity. It’s quite a sight when you see it.

The statues on the ridge stand too far apart. They look lost and lonely. The forest is massive. I gaze around to discern the nature of these lost souls the same way someone might deduce the species of an oyster or a snail from the shell it’s been living in.

If the statues were closer together it might help. It takes a special tool to cut the space between them into tiny pieces.

When I get back to the Frolic Cafe the restaurant is closed but the bar is open. Parley is in rare form, ‘drunk as a shoemaker’ as the proverb says.

“My lord you’re drunk!” I say.

“No Mac. No way. Drunk? A word or two with a friend, that’s all. Nothing wrong with talking to a decent guy when you meet him. Have a little snack together. I know what is what and I know it’s not right to get drunk. But, hey, how’d it go on Statue Ridge?”

I was not going to get any decent advice from Parley. As the proverb goes ‘he was born not like a father nor a mother but like a chance passer-by.’

Flash was cleaning downstairs. He knows more of the truths than most. Parley asks me to pay him for the new soles on my boots. He doesn’t care if the salt statues live or die as long as he gets paid.

When I meet up with Flash downstairs he’s working on a poem.

Between lost souls there exists a bond of sympathy.

No more no less than a piece of crass humanity.

Alone we live out through space and time eternally.

Wind up the golden string to find the key poetically.

“You must be reading my mind, Flash,” I say.

“Just thinking about that total zero,” says Flash. “Do those salt statues really exist?”

“Well,” I say, “they exist only in an idea.”

“So, what’s your point!” asks Flash.

“They are like chess pieces,” I say, “but they’re too far apart to play the game properly. I’m just trying to figure out how to get them all back on the board. I need a tool to cut the space between them.”

Flash sits on one of the stools in the coffee shop. With his shins vertical his thighs horizontal and his back vertical I realize he’s gone geometrical on me. Parley the mathematician would understand but he’s drunk. I on the other hand am random, organic.

“What you need,” he says, “is a mutual enemy. That is what brings people together. You know, a war or a natural disaster.”

“Thanks,” I say. I know he’s right but I’ve seen the eclectic group in the coffee shop—rednecks, hippies, tradesmen, artists, builders, environmentalists, feminists, misogynists—and they all get along. It’s not geometry, it’s random and organic. There is no mutual enemy but they all get on with each other and with themselves. How the hell does that happen?

Outside the salt crystals fall like snow. The flakes are white and beautiful and grow like flowers as they form piles on the ground. The Pomo Indians scavenge all the merchandise from the Frolic. Nothing goes to waste.