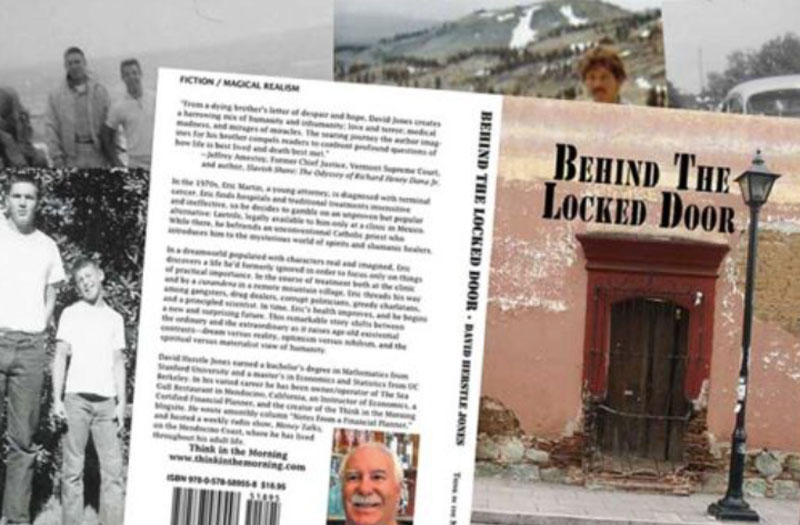

The book is for sale on the Think in the Morning website via PayPal, at Gallery Bookshop and The Book Loft in Mendocino, at The Book Store & Vinyl Cafe in Fort Bragg and as an ebook or paperback at Amazon, Barnes & Noble and other online outlets.

This is the third of a few excerpts we will be posting to pique your interest.

Chapter 30: Professor Snipe

Devon waited outside Professor Snipe’s office. A student emerged, wearing a long flowery dress and a pair of tan Birkenstocks. She glanced at Devon, then quickly walked down the hall and turned the corner. From inside the room, the professor called for Devon to enter.

“Thanks for meeting with me, Professor Snipe. I’m Devon Jennings. I was referred to you by Professor Verne Dahl in the Economics department.”

Snipe thumbed through a report on his desk. He had a pointed nose, beady eyes, and ears that were too small for the head that rested atop of his long neck. His drab tweed jacket was strewn over a plush sofa, leaving only a hard chair for visitors.

“Verne? Oh, right, Laetrile.” Professor Snipe was absorbed in whatever he was reading and didn’t look up. “Hmm. Well, what do you think of spontaneous remission, Jennings? What do you think of diagnostic error? Better yet, as an economist, what do you think of the Hawthorne effect?”

Snipe sat up in his plush upholstered chair and looked at Devon. He rocked his chair from side to side while his bald head bobbled about on his neck.

“How do you mean?”

Devon had come to Professor Snipe in hopes of getting some information that would persuade Eric to return to a hospital in the States.

“Well, young man, patients can recover from cancer on their own for no apparent reason. Do you agree with me there?”

“That’s quite rare, isn’t it?”

“Patients can be misdiagnosed. When they recover from whatever ails them, they attribute their good fortune to the treatment they received at the time. Even a prominent scientist like Linus Pauling believes that nonsense about vitamin C. Do you follow me, my boy? Why, sometimes just paying extra attention to a patient can have a positive effect, like the change in work habits at General Electric that led to the discovery of the Hawthorne effect.”

Snipe’s office was a wasteland of discarded books and journals. He himself was the prototype of the absentminded professor. Still, he was theexpert on Laetrile—a bit of a bumbling expert—an odd combination of the sublime and the ridiculous, like the philosophy professor who shows up to teach a class with jam all over his face.

“I don’t understand, Professor. Are you telling me that the benefits attributed to Laetrile can be explained by such things as spontaneous remission and misdiagnosis?”

“We don’t know, Jennings. We just don’t know. It’s a sign of advanced intelligence to be able to say ‘I don’t know’ in the face of uncertainty, my boy. Too many conclusions are drawn on the basis of insufficient evidence. The data can be difficult to disentangle—too many statistical regressions without the brainpower to do a proper analysis, the kind of thing you do over in the Economics Department. Ha, ha! And another thing, the side effects of chemotherapy and radiation are horrible. When patients stop this type of treatment, as many do when they run off to Mexico for Laetrile, there is going to be a period of time when they feel better simply because those side effects retreat. The federal and state governments haven’t a clue how to handle this Laetrile nonsense. The demand for Laetrile has mushroomed even though it’s worthless and dangerous. Curiously it’s an issue that unites the far right and the far left. Eisenhower would never have allowed such a thing happen, but he’s gone, and a bunch of goofballs run the government today. Laetrile has become the poster child for desperate cancer patients and for those who enjoy sparring with our baffled elected officials. Enforcement of the current laws is next to impossible.”

Professor Snipe stopped swiveling in his chair. He put his elbows on the desk and rested his face in his hands. His beady eyes shot right through Devon.

“Is it really your opinion that Laetrile is worthless and dangerous?”

“I don’t know,” Snipe replied. “You see, I’m not afraid to admit that, son, not at all, but my opinion, if that’s what you ask for, and I should tell you an opinion is not a fact, but for what it’s worth my opinion is that the evidence does seem to lead in that direction. If I may ask, what’s your interest in Laetrile? Are you planning some type of economic study? I could help you get hold of some interesting data that might help you sort things out.”

“My interest is strictly personal. My brother, Eric, is currently at the Clinica Buena Salud in Tijuana getting Laetrile treatment for his colon cancer.”

“Good God, my boy! Talk some sense into him. Get him into a legitimate hospital like Stanford or the UC Med Center, some place where they pay attention to the evidence.”

“That’s just it. He walked out of Stanford after two discouraging weeks. His cancer is inoperable. He felt he was abused in the interests of science. He refused the radiation and chemotherapy and opted for these alternative therapies. I’ve been down to see him. He’s very stubborn.”

Professor Snipe closed his eyes and took a minute to gather his thoughts. When he finally spoke he sounded professorial. “Your brother has a point, my boy. Yes, he does have a point. Those research hospitals, they’re always setting up obstacles to jump over to justify their grants, you see. They’re at the cutting edge—my God we couldn’t live without them, could we—but they do treat patients a bit like sheep. It just goes with the territory, I think. I can’t recommend Laetrile as a reliable cancer treatment, but I can’t entirely dismiss it either, can I? We don’t have all the facts, but the ones we do have… well, I’ve already given my opinion on that. Now, do you have any other questions? I have a class soon.”

“What about Doctor Milagro? What do you know about him?”

“Ah, a charming Latin Casanova. He’s very good, especially with the female patients, you know, they all love him, and then he’s got God in his pocket just in case. Oh, I hope I didn’t offend you, anyway, he claims great success, but he has very little documentation, my boy, very little. He’s had some legal problems, quite rightly in my opinion, but, of course, I’m no expert on legal issues, far from it, but he’s had a rough go after the Jinks affair.”

“What was that?”

“My goodness, you haven’t read about it? What’s this world coming to with no one reading the news anymore, running off down to Mexico without even getting the facts. Oh, forgive me, it’s just a pet peeve of mine, you’re not alone, no one reads the news anymore. Mr. Jinks was an unfortunate young man who suffered from leukemia and was undergoing chemotherapy here in the States. He responded well to the chemo, but his girlfriend—they’re always the ones to make the trouble, aren’t they—his girlfriend wanted him to try the Laetrile she’d heard about from her dentist. Imagine that, a dentist giving advice on cancer, he wasn’t even an orthodontist. So, off they went to visit Milagro last year. The facts are murky. The couple claimed Milagro took Jinks off the chemo. Milagro insisted it was the girlfriend who wanted to stop it. There you are, those facts again, so difficult to untangle. No wonder they all ended up at the attorney’s office.

The illustrious doctor said he advised using both. Whatever the truth, Jinks died shortly after being treated at Milagro’s clinic. Jinks’s family got it all over the news, and there was a big stink. It isn’t possible to lay blame, of course, it never is, is it? Milagro’s reputation suffered, but he still packs in the faithful, a true Mexican phoenix. Oh, the power of faith, my boy, it can move mountains, or so I’ve been told. Anyway, Jinks’s parents brought a lawsuit against Milagro. It was settled out of court. The whole thing died down quickly after that, so I guess I can’t fault you for not having read about it, especially since you’re an economist. Ha, ha! That’s a joke, son; no disrespect to the economists, but they don’t read much outside their field, do they? I hope you haven’t picked up that occupational hazard. Professor Dahl and I get on quite well, but he’s completely focused on the dismal science. He’s a math guy, loves the chalkboard. In another life he might have gone in for whimsical machines and moons like Paul Klee, but he uses his squiggly lines and numbers to decipher the economy. I guess you probably know that already.”

“My brother’s an attorney. He’s smart and talented. He had… has… a great career ahead. I don’t want to see him die unnecessarily because of an emotional decision to chase down a quack treatment. I don’t know how to help him. He seems very determined. What do you think about the claim that Laetrile is a natural cure? Is it true that some natives in remote areas who only eat seeds and fruits full of natural Laetrile never get cancer?”

“Such fantasies are the stepchildren of the idealistic philosophers like Rousseau and Gauguin and other such dreamers. One died of a hemorrhage while walking in the woods, the other of syphilis while dallying on the beach. Nature can be very dangerous, my boy. Cancer is a disease of old age, you see. Your brother is an unfortunate exception. Most people die of other diseases long before cancer gets around to paying them any attention. That’s especially true for the primitives who inhabit those lands of nostalgia, areas where most die of completely preventable maladies owing to the lack of basic medical attention. When the statistics are tallied correctly, those who do live longer get cancer at the same rate as the rest of us. Be assured, I’ve had the number crunchers work that out for me.”

Professor Snipe pushed his chair back and stood with his hands on his desk. “You may not remember that tuberculosis was incurable at the turn of this century. It was commonly believed at the time that sanitation, sun, fresh air, rest, proper food, and better personal hygiene could prevent or cure it. Of course, none of these so-called weapons were of any significance, as you can well imagine, my boy. It was the antibiotics discovered later that eradicated TB, wasn’t it? I’m afraid I don’t have much faith in the healing power of ground-up apricot pits.”

“But, Professor, we don’t have any reliable cure for cancer, do we?”

“We have no cure as yet. The tragedy is that people who have nothing to believe in will believe in anything.”

“Under normal circumstances, Eric would never have gone off to Mexico like this, to some crazy clinic for a bogus treatment.” Devon threw up his hands in frustration.

“Ah, but you see, my boy, here is where I can put on my other hat, being a man of many hats, of which I am quite proud. I wouldn’t try too hard to change your brother’s mind or feel too bad about failing to do so. Let me tell you a dirty little secret about the medical profession, son: They don’t eat their own cooking. I had a good friend, a highly respected orthopedist, a mentor of mine who discovered a lump in his stomach. It was a complete surprise, as such random tragedies often are. He had a surgeon explore the area, and the diagnosis was pancreatic cancer. The surgeon was the best in the country; he’d even invented a new procedure for that very disease, a procedure that could triple a patient’s five-year survival statistics from 5 percent to 15 percent, but with a poor quality of life. Now, let me tell you about my friend. He was brilliant, a medical genius. He read everything about his disease. Then he made a decision that surprised all of us. He was not interested in the treatment offered by the surgeon. He went home and closed his practice the next day. He never set foot in any hospital for the rest of his life. He focused on spending time with family and feeling as good as possible. Several months later he died at home. He never got chemotherapy, radiation, or surgical treatment. Now, what do you make of that, my boy? Sounds crazy, doesn’t it? My point is, how can you know what you would do under similar circumstances? How can I know what I would do? Ultimately, it’s up to each of us to make our own decisions about life and death.”

“I’m sure Eric has good reasons for his decision, but I want to help him get well. I’d feel I was letting him down if I didn’t try to change his mind.”

“Don’t beat yourself up. You said he was a smart young man. Give him a little credit. We each make our own sandwich, and we have to eat it. Can’t blame it on anyone else, can we? If we make tuna fish and find out later that we hate tuna fish, well, we just have to eat it anyway or starve. It’s the way things work, my boy, just the way they work.”

“But what about a change of mind?”

“Your best course of action, in my personal opinion, is to support your brother in his decision. Allow him to enjoy what life he has left as he chooses. He’ll figure it out. He might change his mind, but it’s up to him. It isn’t up to you and it isn’t up to me. There isn’t any better advice I could give you. I’ve enjoyed speaking with you, but now I must leave for a class.”

Professor Snipe took Devon out into the hall, turned quickly to the left, did an abrupt about-face and walked off in the opposite direction.

Devon was confused. He’d expected Snipe to give him a list of persuasive reasons for Eric to return to the States for conventional treatment, but the meeting turned out quite differently. At a loss for what to do next, Devon walked through the campus and came upon a large fountain he’d never seen before. In luxuriant wastefulness, a bulldog was biting great chunks of water and letting it dribble back out of its mouth. Devon stood and watched till the dog had drunk its fill and wandered off alone.

Devon went home to pack for a second trip to Tijuana. This time he was going to stay and see things to the end. Mia and the girls were gone. He hoped the time apart would give them both an opportunity to think things through. He missed Margot and Shawna, but Eric had to be his priority now. The cancer was quickly eating through his brother, erasing the time they had left together. The past played back in Devon’s mind like a defective slideshow with the key scenes missing. At the end of the reel, the pictures stopped. Devon wanted to see the future. Just when you want to see what comes next, everything goes black.

The book is for sale at my Mendocino office (45051 Ukiah Street, above Mendocino Market), on the Think in the Morning website via PayPal, at Gallery Books and The Book Loft in Mendocino, and at Amazon, Barnes & Noble and other online outlets.

I have a picture

of Prof. Snipes in my minds eye, actually reminds me of a neurologist I knew…good character development in a relatively short space of time. Also really like the inserted bits of research into the prof’s dialogue. Looking forward to reading the entire book.

Karyn (Qualicum Beach,BC)

Thanks Karyn. It’s great to hear that someone cares enough to make such a meaningful comment.