A small child is taken to the zoo for the first time. This child may be any one of us or, to put it another way, we have been this child and have forgotten about it. In these grounds – these terrible grounds – the child sees living animals he has never before glimpsed; he sees jaguars, vultures, bison, and – what is still stranger – giraffes. He sees for the first time the bewildering variety of the animal kingdom, and this spectacle, which might alarm or frighten him, he enjoys. He enjoys it so much that going to the zoo is one of the pleasures of childhood, or is thought to be such. How can we explain this everyday and yet mysterious event?

We can, of course, deny it. We can suppose that children suddenly rushed off to the zoo will become, in due time, neurotic, and the truth is there can hardly be a child who has not visited the zoo and there is hardly a grown-up who is not a neurotic. It may be stated that all children, by definition, are explorers, and that to discover the camel is in itself no stranger than to discover a mirror or water or a staircase. It can also be stated that the child trusts his parents, who take him to this place full of animals. Besides, his toy tiger and the pictures of tigers in the encyclopedia have somehow taught him to look at the flesh-and-bone tiger without fear. Plato (if he were invited to join in this discussion) would tell us that the child had already seen the tiger in a primal world of archetypes, and that now on seeing the tiger he recognizes it. Schopenhauer (even more wondrously) would tell us that the child looks at the tigers without fear because he is aware that he is the tigers and the tigers are him or, more accurately, that both he and the tigers are but forms of that single essence, the Will.

Let us pass now from the zoo of reality to the zoo of mythologies, to the zoo whose denizens are not lions but sphinxes and griffons and centaurs. The population of this second zoo should exceed by far the population of the first, since a monster is no more than a combination of parts of real beings, and the possibilities of permutation border on the infinite. In the centaur, the horse and man are blended; in the Minotaur, the bull and man (Dante imagined it as having the face of a man and the body of a bull); and in this way it seems we could evolve an endless variety of monsters – combinations of fishes, birds, and reptiles, limited only by our own boredom or disgust. This, however, does not happen; our monsters would be stillborn, thank God. Flaubert had rounded up, in the last pages of his Temptation of Saint Anthony, a number of medieval and classical monsters and has tried – so say his commentators – to concoct a few new ones; his sum total is hardly impressive, and but few of them really stir our imaginations. Anyone looking into the pages of the present handbook will soon find out that the zoology of dreams is far poorer than the zoology of the Maker.

We are as ignorant of the meaning of the dragon as we are of the meaning of the universe, but there is something in the dragon’s image that appeals to the human imagination, and so we find the dragon in quite distinct places and times. It is, so to speak, a necessary monster, not an ephemeral or accidental one, such as the three-headed chimera or the catoblepas.

…………………………………. Jorge Luis Borghes, The Book of Imaginary Beings

Who am I to argue with Borghes? The zoology of dreams may be poorer than the zoology of the Maker but what a wondrous zoology it is!

Pedro Linares Lopez, ill, consumed by pain and high fever, dreamed of strolling through a beautiful landscape surrounded by peaceful lions with eagle heads, donkeys with butterfly wings and other mythical creatures. The creatures kept repeating the same word to him: “Alebrijes, Alebrijes, Alebrijes.”

So great was his fascination with the creatures that after his recovery he began to build papier-mache models of the animals he had seen in his dream. These complex figurines had bright colors, huge eyes and frequently terrifying fangs. He dubbed them “Alebrijes”.

Pedro Linares started as a skilled maker of carton Judas figures and figurines for Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo and many other artists from the Academia de San Carlos.

If you are lucky enough to visit the world of alebrijes, you will be transformed. Fantastical wild animals, dreamed-up chimeras in bright colors, whimsical combinations of dragons and fish, frogs and butterflies, lizards, otters, bears, anteaters, and insects in unique and original designs—this and much more is the world of alebrijes.

“The wood-carving boom in alebrijes originated in the activities of Oaxaca-based shop owners and two particular carvers—Manuel Jiménez of Arrazola and Isidoro Cruz of San Martín Tilcajete. Jiménez, born in 1919, began to carve wooden figures as a boy to pass the time while tending animals. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, owners of crafts shops in Oaxaca began buying Jiménez’s carvings and selling them to folk art collectors.” (Adventures into Mexico: American Tourism beyond the Border, Nicholas Dagen Bloom editor, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers)

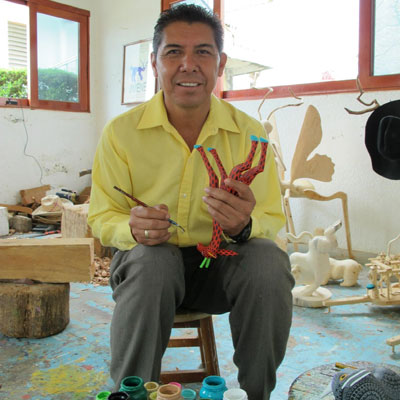

I purchased my first alebrijes from Pepe Santiago in San Antonio Arrazola, Oaxaca, Mexico. Little did I know I was already on my way to becoming a collector. As a young boy I grew up with grandmothers who collected Hummel figurines. I wasn’t particularly impressed. I tried collecting stamps, coins, and sports cards but the hobby never caught on. My great uncle built dozens of model boats and airplanes and I loved them. But, I found the process of making them tedious. I never expected to be a collector of anything. Then I bought my first alebrijes because they amused me. I thought they would make nice gifts for my sons.

Pepe Santiago, San Antonio Arrazola, Lion

Pepe Santiago, San Antonio Arrazola, Blue Rhino

Pepe Santiago, San Antonio Arrazola, Climbing Frog

How much I’ve learned since then.

“I discovered that for commercial reasons all wood carvings from the Mexican state of Oaxaca are called “alebrijes”, even though most of them are cheap mass-produced souvenirs that only share their name with the true works of art called “alebrijes”. Excellent wood carvings may be found all over the world, mainly from China but also from Germany. However, the “genuine” alebrijes by Mexican artists are not only carvings of the highest quality but also represent a symbiosis of sculptures and fantastic paintings; the wooden sculpture, instead of canvas, is the background for three-dimensional paintings.” (ALEBRIJES, Hartmut Zantke)

On one of many trips to Oaxaca, I met Angelico and Isaiah Jimenez, Don Manuel’s two sons, and Isaiah’s son also named Manuel. Sadly Don Manuel died a few years before I met his sons. At their residence, workshop, and display room they showed me around a small museum they created to keep his memory alive.

Manuel Jimenez museum

Angelico posing behind giant grasshopper alebrije, framed awards on the wall.

Early figure sculpture and original tools of Don Manuel

I fell in love with Oaxaca when I visited the Zapotec ruins at Monte Alban in 1985. I ate lunch at El Asador Vasco (still operating today) above the beautiful Zocalo (central plaza). My first visit to the city lasted only a few hours, a side trip from Huatulco during Christmas vacation. I walked around the Zocalo inspecting the giant radishes being carved for the Noche de Rabanos (Night of the Radishes), a festival that dates back more than a century.

I returned a few years later and stayed at Casa Caruso located in a colonial mansion near the beautiful Santo Domingo church. The mansion, built in 1798, was lovingly restored and furnished by the artful eye of Nick Caruso, a eclectic retired New York architect. Nick Caruso sold the building in 2002. It is still operating as Casa Allende.

I met the Jimenez family in Arrazola a few years later. This time I stayed at the beautiful and gracious Casa de las Bugambilias. I’ve stayed there every year since for the past ten years. It’s my home away from home in Oaxaca.

Casa de las Bugambilias and La Olla Restaurant in Oaxaca

The owners and staff of Bugambilias are like a second family. They arranged the trip to meet Angelico and Isaiah Jimenez. I have been buying Jimenez alebrijes ever since.

Nagual rabbit-figure by Angelico and Isaiah Jimenez, Arrazola

This magnificent nahual-rabbit figure was created by Angelico Jimenez. In respect to their father, Angelico and Isaiah both sign their carvings with the name of Manual as well as their own names. Alebrijes by the Jimenez brothers can be found in many magazines, museums, and private collections.

A detailed history of Oaxacan wood carving is available in several books. You can find information on the families and carvers, pictures of alebrijes, and their cultural and historical importance. Three favorites which I own include:

Oaxacan Woodcarving, The Magic in the Trees, Shepard Barbash, Photography by Vicki Ragan, (Chronicle Books, 1993)

Adventures into Mexico: American Tourism beyond the Border, Nicholas Dagen Bloom (Rowman & Littlefield, 2006)

ALEBRIJES, Hartmut Zantke, (Sozialkartei-Verlag, 2011)

It was Manuel Jimenez who discovered the wood that all the carvers now use, copalillo, after experimenting with a dozen different trees. It was Jimenez who moved far beyond the popular tradition of miniature toy making and gave the carvings their larger scale, finer execution, and more ambitious subject matter. And it was Don Manuel, as many now call him, who through his commercial success established the international market for all the carvers who came in the decades after him.

The first time I met Angelico and Isaiah they were having a siesta in the patio next to their house and shop. Angelico had a page of the local newspaper blocking the sun from his eyes. My taxi driver, Solomon, rapped on their iron gate with his key. Angelico jumped up with his brother. By the time they opened the gate, both were awake and greeted us warmly. Angelico’s wide smile and bright eyes immediately put me at ease.

Walking into the garden, I was met by a number of large dragon alebrijes leading into the display room.

An enormous zoo of imaginary creatures greeted my eyes inside the display room. I spoke with Angelico in my broken Spanish and found that he was not only very patient but also had an enormous sense of humor. The taxi driver, Solomon, spoke English and served as a translator when my Spanish proved insufficient. Angelico was very proud of his family and showed me a picture of his son. I decided to chance a joke in my broken Spanish. I asked him how his son could be so handsome when he was so ugly. He broke out into a fit of laughter and then answered “because I have a beautiful wife.”

It was time for the buying to begin.

Polar Bear, Angelico and Isaiah Jimenez, Arrazola

Scorpion, Angelico and Isaiah Jimenez, Arrazola

Armidillo alebrije, Angelico and Isaiah Jimenez, Arrazola

Fox alebrije, Angelico and Isaiah Jimenez, Arrazola

Bull alebrije, Angelico and Isaiah Jimenez, Arrazola

Anteater alebrije, Angelico and Isaiah Jimenez, Arrazola

Isaiah Jimenez is the quiet brother. He walked with us but did not speak. His son, Manuel, learned the art of carving alebrijes from his father and uncle. He is carrying on the tradition in his own name.

Lizard alebrije, Manuel Jimenez, Arrazola

Isaiah Jimenez in his workshop, Arrazola

Having never thought of myself as a collector of anything, I was quickly growing comfortable becoming one. Over the last several years, I’ve managed to acquire well over a hundred alebrijes in several different styles from many different carvers. In future posts I will share more stories and pictures. Alebrijes make me happy. I will close this post with a few more pictures.

Otter and Fish by Angelico and Isaiah Jimenez, Arrazola

Small Bull alebrije by Manuel Jimenez, Arrazola

Flying Fish alebrije by Manuel Jimenez, Arrazola

Small animal alebrijes, Angelico and Isaiah Jimenez, Arrazola

Isaiah and Manuel Jimenez, Arrazola, Oaxaca

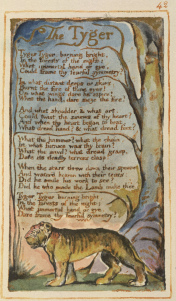

As I drove away in the taxi with my stash of alebrijes, I couldn’t help but think of the famous Tyger poem buy William Blake.

Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

In what distant deeps or skies.

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand, dare seize the fire?

And what shoulder, & what art,

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?

And when thy heart began to beat,

What dread hand? & what dread feet?

What the hammer? what the chain,

In what furnace was thy brain?

What the anvil? what dread grasp,

Dare its deadly terrors clasp!

When the stars threw down their spears

And water’d heaven with their tears:

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the Lamb make thee?

Tyger Tyger burning bright,

In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?

That is a wonderful blog, David. I loved the work and your warm story about the brothers.

What a wonderful post! Thank you for the informative article!

Wonderful blog!! I was on Oaxaca last week and stayed at el Secreto(which is also owned by Pilar)

As this was my first solo international trip and my Spanish is lacking, I was so lucky that Juanita lined up Solomon to help me see all I wanted to see. I spent 2 days with Solomon. He is wonderful man who loves Oaxaca!

So happy you enjoyed this post. Oaxaca is one of my favorite places to visit as you know if you’ve seen some of the other posts on Oaxaca.