As we slowly read the Doleful City of God by Adriana Diaz Enciso (translating from Spanish to English as we go), we are at the same time revisiting the work of William Blake upon whom Enciso’s book is based. The current blog is based on Blake’s concept of the lark as a messenger.

Lark (in the novel Doleful City of God) represents the lark in Blake’s work, for whom this bird is a messenger between men and heaven. In my novel, Lark both Blake’s Lark and Ololon; it is innocence and also truth, which are the same. Adriana Diaz Enciso

“A belief in the supernatural—even based on experience—is not faith, Eric. How shall I say it? In the name o’ God, it is faith, but it’s not the kind of faith you mean, though it might lead to true faith.”

“Then what is faith?”

“You might try thinking of it as a messenger. Yes, a kind o’ messenger.” from Behind The Locked Door

The larks are back out, startling the morning and heralding in the day. When William Blake illustrated Milton’s poem L’Allegro, he choose to enhance these four lines with the illustration that heads this post.

“To hear the Lark begin his flight

And singing startle the dull Night

From his Watch Tower in the Skies

Till the dappled Dawn does rise”

Blake added this explanatory note to clarify his illustration:

“The Lark is an Angel on the Wing

Dull Night starts from his Watch Tower on a Cloud.

The Dawn with her dappled Horses arises above the Earth.

The Earth beneath awakes at the Larks Voice”

Blake’s beautiful illustrations and poetry led Philip Pullman to write fondly in an essay about how he was influenced by William Blake as a young boy (William Blake and Me). I could have written the same essay myself nearly word for word. A short version would go like this. After reading a few Blake poems, I decided to write my senior high school English term paper on Blake. I convinced my mother (we lived alone) to let me drive the family car to Berkeley. It was an ambitious outing for a young boy from a small farm town who had little experience with cities. I managed to spend my limited funds wisely. The first book I bought on Blake was William Blake: The Politics of Vision by Mark Schorer. I have the book in front of me now, heavily worn and marked up. After perusing the book while sitting on a bench along Telegraph Avenue, I bought my second Blake book, William Blake: The Complete Writings with Variant Readings edited by Geoffrey Keynes. (I didn’t know it at the time but Geoffrey’s brother was John, the famous economist.) I devoured both books and several more I ordered from the library. The term paper was a success yet I’ll admit I still don’t understand the magnificent entirety of Blake even today. But, that doesn’t stop me from loving the man and his work.

I love to rise in a summer morn,

When the birds sing on every tree;

The distant huntsman winds his horn,

And the sky-lark sings with me.

O! what sweet company.

from The School Boy by William Blake

William Blake may well be the most impactful poet of all time. Michael R. Burch in the Hypertexts asks the question and then supplies the answer.

Was the enigmatic William Blake England’s greatest poet/artist, and perhaps the world’s? After all, Blake’s influence on modern-day poets, songwriters, artists, filmmakers, novelists, cartoonists and graphic novelists has been intense and far-ranging. William Blake: Influences and References in Popular Culture, Literature, Songs, Films, Etc.

The article goes on to provide a wealth of information on those influenced by Blake. For example: According to John Lennon’s FBI files, when the “fantastically nervous” Beatles met Bob Dylan for the first time, there wan an uncomfortable initial silence, broken by Lennon snarling an insult at Allen Ginsburg. But the unperturbed Beat poet plopped himself down in Lennon’s lap, looked up and asked him, “Have you ever read William Blake, young man?” Lennon, in is best “Liverpudlian deadpan” replied, “Never heard of the man.” But his wife Cynthia chided him, “Oh, John, stop lying!” and that broke the ice.

I’m re-reading the John Steinbeck classic The Grapes of Wrath. It may be that I’m guilty of seeing what I want or hope to see whether it’s there or not but I do think that Blake’s work was an influence on Steinbeck. In this I am not alone (see HERE or HERE).

From as early as I can remember, I have worked to combine my love of science with my love of the arts without diminishing either. I often refer to this quote from Richard Feynman to explain what I mean by this: “I have a friend who’s an artist and has sometimes taken a view which I don’t agree with very well. He’ll hold up a flower and say “look how beautiful it is,” and I’ll agree. Then he says “I as an artist can see how beautiful this is but you as a scientist take this all apart and it becomes a dull thing,” and I think that he’s kind of nutty. First of all, the beauty that he sees is available to other people and to me too, I believe. Although I may not be quite as refined aesthetically as he is … I can appreciate the beauty of a flower. At the same time, I see much more about the flower than he sees. I could imagine the cells in there, the complicated actions inside, which also have a beauty. I mean it’s not just beauty at this dimension, at one centimeter; there’s also beauty at smaller dimensions, the inner structure, also the processes. The fact that the colors in the flower evolved in order to attract insects to pollinate it is interesting; it means that insects can see the color. It adds a question: does this aesthetic sense also exist in the lower forms? Why is it aesthetic? All kinds of interesting questions which the science knowledge only adds to the excitement, the mystery and the awe of a flower. It only adds. I don’t understand how it subtracts.”

Feynman is correct. Blake puts it succinctly

Without contraries there is no progression.

While Blake criticized dogmatic science (something he called “single vision”) he was not anti-science. What he was against was the claim that the scientific view was the only view. Blake would not disagree with Galileo’s claim “and yet it moves.” Not at all. Blake abhorred all dogmatism including religious dogmatism. The gap between the sciences and the arts is diminishing and this is a good thing.

Blake was not a rebel without a cause. I will not cease from Mental Fight, Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand: Till we have built Jerusalem, In Englands green & pleasant Land. (Jerusalem) He was a firm believer in freedom. One Law for the Lion & Ox is Oppression. (The Marriage of Heaven and Hell) A Robin Red breast in a Cage Puts all Heaven in a Rage. (Auguries of Innocence) And, he refused to be governed by religious, political or industrial mores. To God: If you have form’d a Circle to go into, Go into it yourself & see how you would do.

In contra to Blake who wrote You never know what is enough unless you know what is more than enough, I’ll close this blog for now with a few more of his words on the lark.

“Thou hearest the Nightingale begin the Song of Spring;

The Lark sitting upon his earthy bed: just as the morn

Appears; listens silent; then springing from the waving Corn-field! loud

He leads the Choir of Day! trill, trill, trill, trill,

Mounting upon the wings of light into the Great Expanse:

Reecchoing against the lovely blue & shining heavenly Shell:

His little throat labours with inspiration; every feather

On throat & breast & wings vibrates with the effluence Divine

All Nature listens silent to him & the awful Sun

Stands still upon the Mountain looking on this little Bird

With eyes of soft humility, & wonder love & awe.

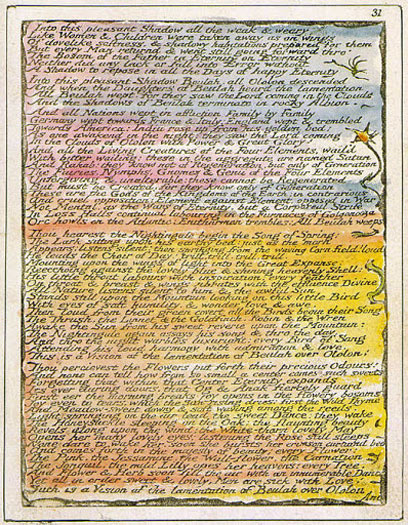

Milton, Plate 31

Milton, Plate 31, William Blake

Hi David, sorry that is not entirely pertaining to the piece above but I was amazed to find this resource after I spoke with my grandfather, Mike Nielson, about some of his experiences working with David Clayton. I’d really love to learn more about what the community was like back then, so any help would be greatly appreciated. Thank you again for providing such an enriching source, one that makes me incredibly appreciative of the people who came together for a community.