“Improvement makes straight roads; but the crooked roads without Improvement are the roads of genius.”

William Blake

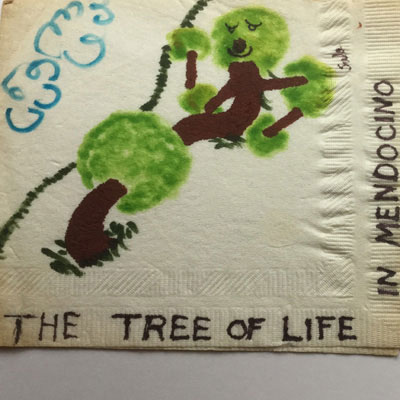

Napkin Art, Sea Gull Cellar Bar, artist unknown

On Highway 128 just before the newly built Mountain House Estate, there is a crooked tree that stands near the point of highest elevation between Cloverdale and the Mendocino Coast. A series of sharp, nausea inducing turns punctuates the two-lane road that leads up to the tree if you’re driving west. The tree was there in 1972 when I moved from Berkeley to Mendocino. I convinced myself at the time the crooked tree was the dividing point, the point of no return between city and country.

My good friend, Bill Zacha, must have seen that tree fifteen years before me when he moved to Mendocino to start the Mendocino Art Center. “Neon signs, motels, express highways bringing death or disorder or smog – no, sir, you can have them. And modern-type buildings without any feeling of life in them – you can have all that junk too. I like a town that has peace and dignity and beauty, where you can walk down the street and breathe deep and shout, ‘Man! Am I glad I live here!’“

I didn’t know Bill Zacha in 1972. In fact, I hardly knew anyone who lived in Mendocino. In a few years, by virtue of running the Sea Gull Restaurant, I would meet hundreds of fog-eaters, a term used to describe coastal dwellers by some of the old timers in the Anderson Valley. Fog-eater is one of many odd words in the strange lingo of Boontling that was developed in the Anderson Valley in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. A history of Boontling complete with a dictionary was published by Charles C. Adams in 1971, one year before I passed that crooked tree on my way to Mendocino.

Lots of people, particularly young people, were starting new lives in those days. Call them optimistic but much of lasting value was accomplished. The artist Charles Stevenson, who like many talented transplants to the Mendocino coast waited tables and swept up at the Sea Gull to survive, summed it up best: “It was my longtime dream to be part of a golden age of art. What happened in Mendocino gave us the feeling that we could influence the course of events by our dreams and visions. The people who came helped complete our connection with the arts and I think we did have a golden age.”

A couple of years before I moved to Mendocino, a high school buddy of mine left with Stephen Gaskin’s caravan to start The Farm outside Nashville, Tennessee. People had been moving to Mendocino for years to start their own communal living arrangements in a quiet and beautiful place. I moved for another reason, to buy and run a restaurant. I was 26. For the past eight years I’d been isolated in a comfortable if challenging college environment. Suddenly, I found myself employing dozens of people, many older than I was, and responsible for a thriving restaurant when I had little idea how to cook or make drinks. It was the real world, and I was definitely in over my head.

The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Proverbs of Hell, William Blake

When skill fails you must rely on luck and sheer will. Fortunately, I had both. Luck came in the form of incredible employees who accepted and helped me in every possible way, in the integrity of the previous owners who quickly became friends, and in the irrepressible spirit of the community.

There were difficulties. Shortly after I arrived, the day cook gave two weeks notice. I realized then that learning to cook was no longer an option. I put on an apron and followed her into the kitchen. With a look of surprise she asked what I thought I was doing. I told her if I had two weeks, they were going to be two weeks of personal training. She laughed and then she did everything possible to teach me enough to get by on my own when she left.

Other problems arose. Every time I walked out the back of the restaurant, down the stairs, and along the wooden walkway to the Inn, I noticed that there seemed to be a swamp forming. I asked Martin Hall, the previous owner, to walk with me so he could see what I saw.

“Oh, it’s nothing. The ground here is always a little wet. It dries up when the sun comes out.”

I reached down and picked out a piece of broccoli from the muck.

“What about this?”

Martin turned his head to one side and smiled quizzically under his thick mustache.

“That’s odd. I’ve never seen anything like that before.”

The next day I climbed under the restaurant and discovered that the drain to the kitchen sink where we prepped vegetables and fish and chicken and calamari had slipped loose from a hose. The waste water was emptying out under the restaurant. There really was a swamp and the smell wasn’t attractive. I panicked when I first saw it.

Someone said to call Orval. That was my first lesson in the social dynamics of the Mendocino coast. Orval Richards was a plumber and a good one. He spoke with a folksy accent, disdained answering machines, and walked straight ahead, a man with a purpose, as he passed by the hip clientele of the Sea Gull. He knew what needed to be done. He laid down a bunch of cardboard, scooted his corpulent frame through the crawl space under the restaurant on top of the stinking muck and affixed a permanent drain pipe to the kitchen sink which would not pop off from the weight of the slop that descended through it. He scattered around enough bags of lime to cover all the mess which quickly eliminated the smell. He scooted out, cleaned up, thanked me for the job, took my check, and left. Needless to say, whenever I had a plumbing problem in the future, I called Orval.

Most of the blue collar fog-eaters lived in Fort Bragg, ten miles up the highway from Mendocino. The schools, the politics, and the day-to-day lives in the two areas were vastly different. Artists, actors, writers, musicians and a wide variety of counterculture types had a preference for Mendocino as did the rich tourists. Loggers, fishermen, contractors, mechanics, and traditional retail storeowners found Fort Bragg more affordable. The division wasn’t premeditated or clear-cut. It was self-organizing, birds of a feather flock together. I remember hiring Ed Bingham, a master tile setter, to build a shower in the upstairs storeroom where I was living at the time. He spoke with a southwestern twang and smiled when I met him.

“I told the wife I was going on a job down to Mendacina, and she laughed, ‘Aah, that’s where the colorful people live, honey. Watch out for them hippy chicks.'”

Ed did many tile jobs for me over the years. He set tiles the old fashioned way in cement. He taught me to be his hod carrier, that is to mix and carry the cement. I asked him how he became a tile setter.

“As a young kid I was working down in Arizona as a roofer on a big hotel job. It was hotter than Hades up there. I looked down and saw the tile setters cutting tile in the shade with plenty of running water. I told the boss right then, I wanna be a tile setter. Been a tile setter ever since, nearly forty years now. Ever once in awhile I getta young guy wants to work with me for a couple a weeks to learn how to be a tile setter. Sure, come on for a week or two, I tell’m. I’ll teach ya everything I’ve learned in forty years!” Then he laughed long and hard and told me to hurry it up with the cement.

The Sea Gull was truly a melting pot of coastal residents, hip, straight, those on hard times and those living in the high cotton. A regular group of locals populated the coffee shop. Jake Jacobson would come into the coffee shop after cutting hay leaving little scraps of hay chaff everywhere he went. He always ordered the same, a green salad with Roquefort dressing and a glass of water. He really hated spending money. Ina, who worked at the local grocery owned by the Mendosas, would always order a plain green salad. She’d reach in her purse for a bag of tuna or crab she brought at the store and sprinkle it onto the salad. Getting used to such oddities was part of fun of running the place.

Some regular customers had their own special meals that eventually made the menu with their names attached such as the Laing special named for a retired schoolteacher who lived on the corner above the barber shop, the Miles special named for a local dentist, and Big John’s special named for Big John Rogers who was the mechanic at the Shell Garage across Lansing Street. Big John and Helen Terrell used to stand on milk cartons to wash the windows of the trucks that bought gas there. Once I took my Datsun truck to Big John when it wasn’t running well. He opened the hood then closed it back up. “I don’t work on those foreign cars,” he said with a smirk.

I don’t know how many times I’ve passed that crooked tree on 128. Always, without fail, it awakens that feeling of moving from one world into another as if for the first time. Going west, my whole body relaxes. When I’m heading east, it tenses up. That tells you something.

Love it, David!

I remember the gals from upstairs in Mendosa’s would come in for lunch, take the front round table in the dining room, and start off lunch with a round of boilermakers…eat lunch, and go back to work.

Now that is country living!

I really enjoyed this Pop! I have heard you tell bits and pieces of these stories over the past 28 years, many of them around the dinner table and many over glasses of wine. It was a joy to read this and imagine your early days in Mendo. It really is nice to feel a connection with the place you live and the wonderful feeling when you return home.

AND MORE OF THIS PLEASE OH PLEASE

Yes tell us more stories.

Terry