There was a man, a Frenchman, you wouldn’t know about him, my child. . .He was a good man, a holy man, and he lived in sin all through his life, because he couldn’t bear the idea that any soul could suffer damnation. . .This man decided that if any soul was going to be damned, he would be damned too. He never took the sacraments, he never married his wife in church. I don’t know, my child, but some people think he was—well, a saint. Graham Greene, Brighton Rock

No one screams against this Hell. No one protests. And if they abhor what they see, they do not have the courage to damn the damned. One alone would not have failed us. Péguy would have spoken, I hope, he would have let loose his scream. He is not here, and there is no one else. André Suarès, 1939

I don’t know if you watched the bizarre events at the Alfred E. Smith Memorial Foundation Dinner last week. The dinner was the kind of spectacle that sets America apart from the rest of the world. From Maria Bartiromo’s cleavage to Rudi Giuliani’s scowl to the two presidential candidates praying with Cardinal Dolan, America’s glitz and wealth were center stage together with the utter inability of the participants to give a positive answer to Rodney King’s lonely question “can we all get along?” We enjoy such events despite the First Amendment. As Thorsten Veblen (The Theory of the Leisure Class) and others (notably economist Robert Frank) have pointed out, the rich are entertaining. And, after all, the money goes to needy children.

Watching the dinner and especially the faces of those listening to the speeches did make me laugh. Less obviously, it made me think of the Frenchman Charles Péguy.

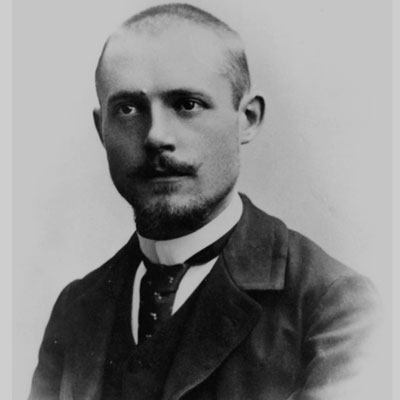

“Who,” you might ask, “is Charles Péguy?” Born in 1873, he called himself a peasant and insisted that French peasantry represented what was best in France. He was a poet, a writer of essays, a nationalist, and a socialist. He was also a non-practicing Catholic after living as an atheist for much of his life. While a young boy, his parish priest asked him if he wished to become a priest some day. “No,” said the child, “that is not what I have in mind.” [Basic Verities, p. 15] On the first day of the first battle of the Marne in 1914, about twenty-five kilometers from Paris, Péguy suffered a fatal bullet to the head. He was 41. “For God’s sake, push ahead!” are said to have been his last words.

I first read Charles Péguy some fifty years ago at Stanford University when I took a course from Michael Novak, a popular young professor at that time. Novak was a socialist in those days and a liberal Catholic. Today he is comfortably housed at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank. He is a firm advocate for capitalism and has spent the better part of the past thirty years or more trying to reconcile his belief in capitalism with his Catholic religion to the detriment of both in my opinion. He is no longer the man I met at Stanford. But, neither am I the same. Péguy wrote about the mystery of aging: “the old man, she says, does not know what it is to get older, (he no longer knows it), (happily), he doesn’t know, he no longer knows anything about aging. But the man of forty, who feels recently emerged from his lost youth, he knows what it is to get older and to age.” [Clio, 3:1191 quoted in The Passion of Charles Péguy by Glenn H. Roe]

His [Péguy’s] socialism, or more exactly the eminent dignity which he bestowed upon poverty in the world was already the Gospel … Péguy’s socialism was far more akin to the socialism of Saint Francis than to that of Karl Marx. J. & J. Tharaud [quoted from Basic Verities]

It was impossible for Péguy to do anything half-heartedly. He displayed a tendency toward exaggeration, stridency, and overstatement. His writing is repetitive, long-winded at times, and can be exasperating. When François Mauriac was told by Mr. Julian Green that he was translating Péguy’s highly rhetorical prose poem The Mystery of the Charity of Joan of Arc, Mauriac made this disparaging comment: “What a pity,” he remarked, “someone does not translate him into French.” [quoted from Basic Verities]

Charles Péguy wedding photograph, 28 October 1897

And yet … and yet.

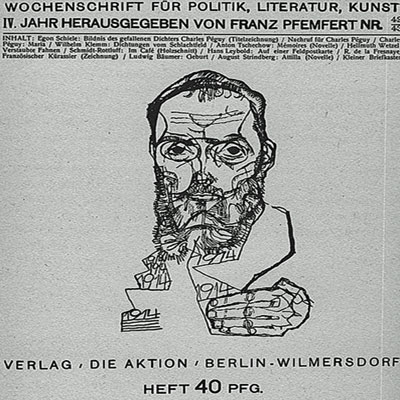

Péguy has much to say if we would only take the time to listen. Especially today. He is known mostly for his aphorisms derived from the essays he wrote in over a hundred Cahiers de la Quinzaine (Fortnightly Note-books) published by his own publishing company. Some of his essays and poems were collected and translated by Anne and Julian Green in Basic Verities, a book long out of print but available from used book stores and well worth the trouble of seeking out.

The boutique of the Cahiers de la Quinzaine, 8 rue de la Sorbonne, Paris, March 1902

The aphorisms, some of which I will list below, seem particularly relevant in the current political atmosphere. To discuss Péguy only through these short, crisp sayings is to do him a great disservice. I apologize in advance. I can only hope that this brief introduction will lead you on to his longer work. Péguy deserves to be read. He must be read. The aphorisms are unforgettable once you read them. And, they ring true to the heart. Take time to consider each one, to mull it over, to consider how it might apply to you and your life, to today and our times.

………………..

Everything begins in mysticism and ends in politics.

He who does not bellow the truth when he knows the truth makes himself the accomplice of liars and forgers.

We must always tell what we see. Above all, and this is more difficult, we must always see what we see.

It will never be known what acts of cowardice have been motivated by the fear of not looking sufficiently progressive.”

The revolution is moral or not at all.

To ask for victory and not to feel like fighting, I consider that to be ill-bred.

It is better to have a war for justice than peace in injustice.

He who allows things to be done is like him who orders them to be done.

When a man dies, he does not just die of the disease he has: he dies of his whole life.

Short of genius a rich man cannot imagine poverty.

The life of an honest man must be, in this sense, a perpetual apostasy and revolt, the honest man must be a perpetual renegade; the life of the honest man must be, in this sense, a perpetual infidelity.

A review only continues to have life if each issue annoys at least one-fifth of its readers. Justice lies in seeing that it is not always the same fifth.

Tyranny is always better organized than freedom.

Homer is still new this morning, and noting perhaps is as old as today’s newspaper.

Any father whose son raises his hand against him is guilty of having raised a son who raises his hand against him.

First, reason is not wisdom and neither one nor the other is logic. And the three together are not the intellect. They are three—and four—orders; they are three—and four realms, and there are many others.

The greatest revolutions, in any domain, were not made with and by extraordinary ideas, and it is indeed the lot of genius to proceed by the simplest ideas… When a simple idea takes hold, there is a revolution.

The references you do not verify are the good ones.

It is innocence that is full and experience that is empty. It is innocence that wins and experience that loses.

Love is rarer than genius itself. And friendship is rarer than love.

A great philosophy is not one that passes final judgements and establishes ultimate truth. It is one that causes uneasiness and starts commotion.

A word is not the same with one writer as with another. One tears it from his guts. The other pulls it out of his overcoat pocket.

………………..

In the words of Glenn H. Roe, author of The Passion of Charles Péguy:

Now, more than ever perhaps, we should find strength in his [Péguy’s] abiding conviction that literature in particular, and the humanities in general, are essential pedagogical components in the formation of a free and equitable society—one intent on developing and promoting critical thinking skills, engendering cultural consciousness and historical responsibility, and creating competent and compassionate democratic citizens.

The aphorisms come from longer works. Here are two examples. First, the importance of speaking out for the right, the good, the truth. It is never easy. I think here of another aphorism by the free-thinking philosopher Walter Kaufmann: “Modesty is so much easier than honesty because it is compatible with sloth.” (The Faith of a Heretic)

WAR

JOAN OF ARC SPEAKS ;

Do you know that we, who see all this going on under our eyes and are content at present with empty charities, since we do not want to kill war, do you know that we are accomplices in all this? We who let the soldiers do as they wish, do you know that we too torment bodies and damn souls? We too, even we, strike crucified Jesus on the cheek. We too, even we, profane the imperishable body of Jesus.

As accomplice, an accomplice, it’s like an author. We are accomplices in this, we are the authors of this. Accomplice, accomplice, it is just as if you said author.

He who allows things to be done is like him who orders them to be done. It is all one. It goes together. And he who allows things to be done, just like him who orders them to be done, it is altogether like him who does them. Because he does show courage, at least, in doing. He who commits a crime has at least the courage to commit it. And when you allow the crime to be committed, you have the same crime, and cowardice to boot. Cowardice on top of it all.

There is everywhere infinite cowardice.

And now, from Basic Verities, one of my favorite essays by Péguy. Several of his most famous aphorisms appear here. It is an essay about truth and how the search for truth threatens every one of us to the core. Péguy believed in following your passion completely but he also understood the guiding principle of reason and the necessity of changing when change is warranted. Passion without reason leads to fanaticism. Reason without passion leads to death.

THE SEARCH FOR TRUTH

I believe that in the history of the world one could easily find a very great number of examples of persons who, suddenly perceiving the truth, seize it. Or, having sought and found it, deliberately break with their interests, sacrifice their interests, break deliberately with their political friendships and even with their sentimental friendships. I do not believe that one finds many examples of men who, having accomplished this first sacrifice, have had the second courage to sacrifice their second interests, their second friendships. For it commonly happens that they find their new friends are worth no more than the old ones, that their second friends are worth no more than the first. Woe to the lonely man, and what they fear most is solitude. They are most willing, for the sake of the truth, to fall out with half of the world. All the more so when, by thus falling out with half of the world–not without a little repercussion–they usually make partisans among the second half of the world; partisans who ask nothing better than to be the antagonists of the first half. But if, for the love of this same truth, they foolishly go about breaking with this second half, who will become their partisans?–

A brave man–and so far, there are not many–for the sake of the truth breaks with his friends and his interests. Thus a new party is formed, originally and supposedly the party of justice and truth, which in less than no time becomes absolutely identical with the other parties. A party like the others; as vulgar; as gross; as unjust; as false. Then for this second time, a superbrave man would have to be found to make a second break; but of these, there are hardly any left.–

And yet, the life of an honest man must be an apostasy and a perpetual desertion. The honest man must be a perpetual renegade, the life of an honest man must be a perpetual infidelity. For the man who wishes to remain faithful to truth must make himself continually unfaithful to all the continual, successive, indefatigable renascent errors. And the man who wishes to remain faithful to justice must make himself continually unfaithful to inexhaustibly triumphant injustices.

Humanity will surpass the first dirigibles as it has surpassed the first locomotives. It will surpass M. Santos-Dumont as it has surpassed Stephenson. After telephotography it will continually invest graphs and scopes and phones, all of which will be tele and one will be able to go around the earth in less than no time. But it will always only be the temporal earth. And it will even be possible to burrow inside the earth and pierce it through and through as I do this ball of clay. But it will always only be the carnal earth. And it cannot be imagined that any man ever, nor any humanity, in a certain sense–which is the right sense–can ever intelligently boast of having surpassed Plato. I will go further. I add that a cultured man, a really cultured man, cannot even imagine the meaning of a claim to have surpassed Plato.

A great philosophy is not that which passes final judgements, which takes a seat in final truth. It is that which introduces uneasiness, which opens the door to commotion.–

A great philosophy is not that which is never defeated. But a small philosophy is always that which does not fight.–A great philosophy is not a philosophy without reproach, it is a philosophy without fear.

Genius is not talent brought to a very high degree, nor even to its limit, but is of another order than talent.

It is in the innate character of genius to proceed by the simplest ideas.

Love is rarer than genius itself.–And friendship is rarer than love.

The worst of partialities is to withhold oneself, the worst ignorance is not to act, the worst lie is to steal away.

Any father whose son strikes him is guilty: of having conceived a son capable of striking him.

When a man lies dying, he does not die from disease alone. He dies from his whole life.

So it is that the Alfred E. Smith Memorial Dinner with all the trimmings got me to thinking about my friend Charles Péguy. How do these things happen? Why do they happen? No one knows. Associations inside the complicated mind of man are something we have yet to understand. Synapses, neurons, axons, dendrites–they pop off their peculiar electrical signals at the most unexpected times. Or not.

I invite you to read some of Péguy’s longer essays and poems. They are not always easy but they are rewarding. The Nobel recipient Andre Gide, in reviewing Basic Verities, described Péguy with these lovely images:

Twelve sentences would have sufficed for me summing up these 250 pages. But the repetitions . . . are intrinsic and a part of the whole. . . . Péguys style is like that of very old litanies . . . like Arab songs, like the monotonous songs of the Landes; one could compare it to a desert; a desert of alfalfa, of sand, or of pebbles . . . each looks like the other, but is just a little different, and this difference corrects, relinquishes, repeats, or appears to repeat, accentuates, affirms, and always more certainly one advances . . . the believer prays the same prayer throughout, or at least, almost the same prayer . . . almost without his being aware of it and, almost in spite of himself, beginning all over again. Words! I will not leave you, same words, and I will not acquit you while you still have something to say, We will not let Thee go, Lord, Except Thou bless us.

Péguy and his comrades, as was typical in the battles of 1914, are buried in a mass grave close to the spot where he fell. His name is recorded on a screen wall in the war cemetery near Villeroy.

Ironically Péguy wrote his own epitaph though he didn’t know it at the time. In 1913, a year before he died, he wrote this now famous poem.

BLESSED ARE

By Charles Péguy

Blessed are those who died for carnal earth

Provided it was in a just war.

Blessed are those who died for a plot of ground.

Blessed are those who died a solemn death.

Blessed are those who died in great battles.

Stretched out on the ground in the face of God.

Blessed are those who died on a final high place,

Amid all the pomp of grandiose funerals.

Blessed are those who died for carnal cities.

For they are the body of the city of God.

Blessed are those who died for their hearth and their fire,

And the lowly honors of their father’s house.

For such is the image and such the beginning

The body and shadow of the house of God.

Blessed are those who died in that embrace,

In honor’s clasp and earth’s avowal.

For honor’s clasp is the beginning

And the first draught of eternal avowal.

Blessed are those who died in this crushing down,

In the accomplishment of this earthly vow.

Blessed are those who died, for they have returned

Into primeval clay and primeval earth.

Blessed are those who died in a just war.

Blessed is the wheat that is ripe and the wheat that is gathered in sheaves.

I’m reading Village of Secrets by Caroline Moorehead.

She quoted ” I will disobey if justice and truth demand it” to Peguy.

I had to find out who this man was and searched for him, read his biography etc. and ended up on your site. I will come again…

Thanks. I’m always happy to introduce someone to Peguy. I first discovered him in college when I read his wonderful book Basic Verities. He was a remarkable human being.