[Click on BLUE links for sources and information]

Overproduction of growth hormone causes excessive growth. In children, the condition is called gigantism. In adults, it is called acromegaly. Excessive growth hormone is almost always caused by a noncancerous (benign) pituitary tumor. Ian M. Chapman, Gigantism and Acromegaly

Shopping is cheaper than a psychiatrist. Tammy Faye Bakker

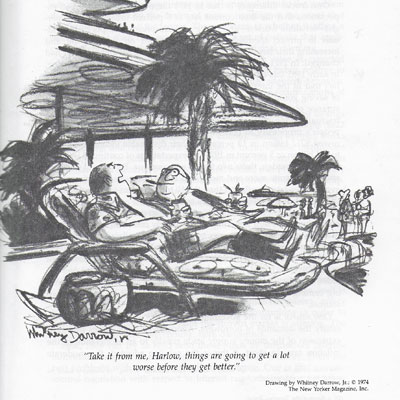

There’s nothing worse than an old man complaining that things are not as good as they used to be or that doom and gloom is just around the corner. Neither of these is what I want to discuss.

Whitney Darrow, Jr. 1974, The New Yorker Magazine, Inc.

Nor do I wish to parrot the bobos (bourgeois bohemians) so humorously described by David Brooks (Bobos in Paradise)—those who expect to save the world by drinking designer coffee and wearing hemp clothing. You could justifiably call me a bobo. I am a certified member of what one of my friends calls the lucky sperm club, someone who grew up with privileges. And, my political views are liberal. However you classify my thoughts, Boboism is irrelevant since it’s been replaced with a Basket of Deplorables under President Trump.

I will make a different argument, a broad statement: the fundamental basis of the American economy is flawed. Now, that’s a shocking thing to say coming from a student of economic theory and history and who has no intention of throwing out the baby with the bathwater (even Karl Marx recognized the progressive nature of capitalism although he argued that the system was also flawed). Let me explain.

The bourgeoisie has subjected the country to the rule of the towns. It has created enormous cities, has greatly increased the urban population as compared with the rural, and has thus rescued a considerable part of the population from the idiocy of rural life. Just as it has made the country dependent on the towns, so it has made barbarian and semi-barbarian countries dependent on the civilised ones, nations of peasants on nations of bourgeois, the East on the West. Marx, Chapter 1 The Communist Manifesto

I always knew about the flaws and so did many others. But, those who study business and economics or who run a business, are prone to accept a set of assumptions as facts. The reason has something to do with what I will loosely call the economic mindset. [At this point, my friends further to the left will say: “told you so” and I will respond “mea culpa”.]

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

What I call the economic mindset includes the idea that the principal objective of government should be to increase the rate of economic growth, that the best way to achieve this objective is through the free operation of private markets, that human desire is insatiable (more is better), that consumers are well informed and their decisions sacrosanct and that consumption is not only enjoyable but necessary for a vibrant economy, that a rising tide lifts all boats, and that government is inherently inefficient compared with the private sector.

The market serves as a sort of civic tranquillizer, the post-modern opium of the people. Clive Hamilton, The Growth Fetish

None of these assumptions are facts. Each contains some truth and some falseness . To quote former Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan: “Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not to his own facts.

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

To determine the facts, we need evidence. The evidence can change over time and between cultures. Therefore, eternal vigilance is required. As John Maynard Keynes reportedly said: “When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?”

If we ignore centuries of religious and philosophical thought, the great satirists (such as William Blake, William Hogarth, Jonathan Swift), and even the so-called father of economics, Adam Smith (The Wealth of Nations), we might date the first objections to the economic mindset at the turn of the twentieth century with the rise of the so-called institutional economists (see list below). These economists both satirized and challenged the economic mindset. The concerns they raise have mostly not been incorporated into economic theory or into the goals and policies used to run a country. Here is a short list (details in their books listed below).

2. More equal societies are happier societies. A more unequal society is more unhappy, even if most people’s incomes are higher than they would be in a more equal society.

3. Depression is not the only unexplained psychological disorder in wealthy societies. Increasing numbers of people are easily distracted, find it difficult to concentrate on the task before them, have difficulty listening to what is being said, talk too much, cannot sit still for more than a few minutes, and are drawn to physically dangerous activities without considering the possible consequences.

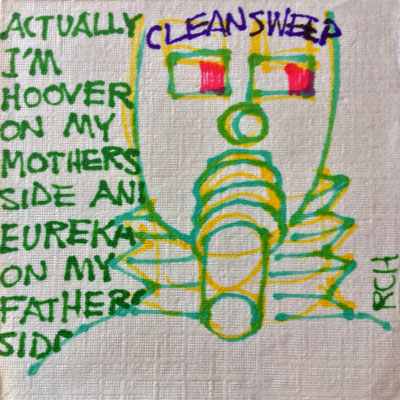

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

4. Economic growth does not create happiness: unhappiness sustains economic growth.

Naomi Klein argues in No Logo that, ‘Rather than serving as a guarantee of value on a product, the brand itself has increasingly become the product, a free-standing idea pasted onto innumerable surfaces. The actual product bearing the brand-name has become a medium, like radio or a billboard, to transmit the real message’. The product itself is incidental to the company and indeed in many cases its manufacture is contracted out to factories in the Third World. Klein refers to this as a ‘race towards weightlessness’, in which the company distances itself from the manufacture of a product and becomes a shell devoted to marketing. In the world of the weightless corporation, the real work is to build a brand rather than make a product. This represents a shift from the product itself being of true value: what is of true value is ‘the idea, the lifestyle, the attitude’, and it is these associations with a product that require the real investment and creativity. Clive Hamilton, The Growth Fetish

5. Consumption no longer occurs in order to meet human needs; its purpose now is to manufacture identity.

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

6. Science, technology, markets, growth—these forces are taking over the world and leading to homogenisation of societies, political systems, consumption patterns and tastes.

“Conformity, fear, violence – that was the cancer in the heart of society, not LSD or psychedelic crazies preaching make love, not war.” Ken Kesey

7. The markets’ are not politically neutral. They constantly make judgments, or at least their actors make judgments, about the political desirability of all manner of policy decisions by national governments. For instance, they have a strong preference for measures that reduce inflation at the expense of higher unemployment, for measures that reduce public spending in ways that diminish welfare provision, and for precedence to be given to ‘development’ over environmental protection.

8. What the idea of consumer sovereignty refuses to recognize is that people’s preferences are not created ex nihilo: they are formed by the society they live in—which in the present case means in large measure and increasingly by the messages of the marketing society. In the post-modern world people create their own selves, but they do not create them just as they please: they create them under circumstances and with materials made and transmitted by the ideology of growth fetishism and the marketing machine.

An alcoholic would prefer more drinks, but we don’t measure their wellbeing by the number of drinks they have. Clive Hamilton

9. There is a time cost to consumption and a maintenance cost and both restrict the time available to “smell the roses.”

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Max Efroym artist

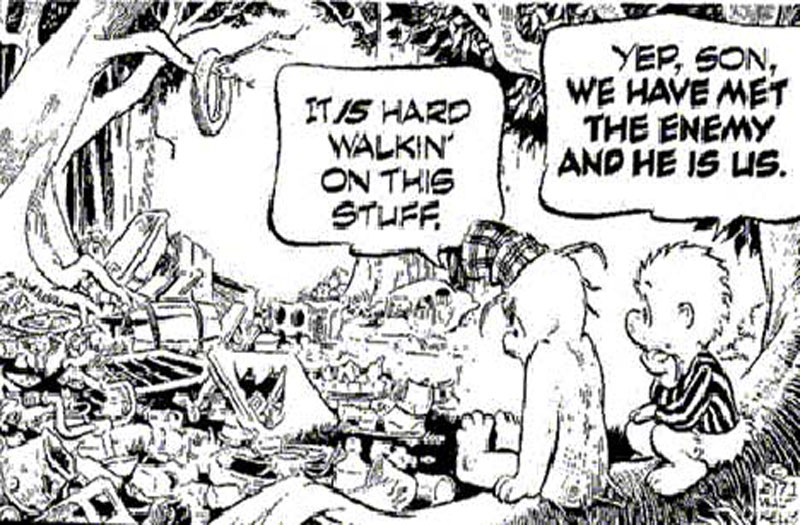

10. Expanding population, technology and affluence have unintended ‘spillover’ effects or social costs (negative externalities in the lingo of economists).

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

11. Ever since Adam Smith, the central teaching of economics has been that free markets provide us with material well-being, as if by an invisible hand. A fundamental challenge to this insight is that markets harm as well as help us. As long as there is profit to be made, sellers will systematically exploit our psychological weaknesses and our ignorance through manipulation and deception. Rather than being essentially benign and always creating the greater good, markets are inherently filled with tricks and traps and will “phish” us as “phools.”

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

To the extent the above statements are true, we are like the drunk looking for his keys under the streetlight.

A policeman sees a drunk man searching for something under a streetlight and asks what the drunk has lost. He says he lost his keys and they both look under the streetlight together. After a few minutes the policeman asks if he is sure he lost them here, and the drunk replies, no, and that he lost them in the park. The policeman asks why he is searching here, and the drunk replies, “this is where the light is”.

It’s long past time for economists to reassess goals and the means to achieve them. And, long past time for us to learn how to use our leisure wisely and how to consume wisely. Is there a difference between what people say they want and what they really want? Does ‘what people have’ include only things that can be bought and sold? Does what people have actually satisfy them? Is what people want independent of what they have or does more ‘having’ drive up the level of wanting, so that the two can never meet and consumption is doomed to be a labour of Sisyphus? (Clive Hamilton)

To those who sweat for their daily bread leisure is a longed-for sweet – until they get it. There is the traditional epitaph written for herself by the old charwoman: –

Don’t mourn for me, friends, don’t weep for me never, For I’m going to do nothing for ever and ever.

This was her heaven. Like others who look forward to leisure, she conceived how nice it would be to spend her time listening-in – for there was another couplet which occurred in her poem: –With psalms and sweet music the heavens’ll be ringing, But I shall have nothing to do with the singing.

Yet it will only be for those who have to do with the singing that life will be tolerable and how few of us can sing! J. M. Keynes

Institutional Economists

A few famous economists who challenged the economic mindset and whose books are still read include Thorstein Veblen (The Theory of the Leisure Class), E. J. Mishan (The Costs of Economic Growth), John Kenneth Galbraith (The Affluent Society), Tibor Scitovsky (The Joyless Economy), Staffan B. Linder (The Harried Leisure Class), Robert Frank (Luxury Fever), Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein (Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth and Happiness), Clive Hamilton (The Growth Fetish), George Akerlof and Robert Shiller (Phishing for Phools: The Economics of Manipulation and Deception), and Daniel Kahneman (Thinking, Fast and Slow).

David,

I so appreciate this site! Not just for the nostalgia that comes from being a loyal Seagull customer, but Roy and JC got such inspiration from being there.

Thanks a lot,

J. Frank

You’re welcome! I get a lot of satisfaction from visiting the good ole days.

Great piece, KD

In the words of Junior, “I love it.!”. It was not in Russian and I didn’t even have to lift Ukranian sanctions!