[Click on BLUE links for sources and more information]

I remember the Fuller Brush man calling on my house when I was in grade school. As I recall, he had a box that opened to an array of brushes one of which I chose and paid for with my own money. I worked at the local grocery store. I still have that brush. It is sixty years old now and I use it every day. It’s been on every trip I’ve ever taken and it is as good as new with the exception of spot on the handle where cologne with an alcohol base burned through the protective coating. My family calls it the “hairloom,” a play on the word heirloom.

In this day and age heirlooms are hard to come by. In Cuba they still drive cars from the 50s and 60s (see Cuba and Planned Obsolescence) but not so much in the U.S. of A. I remember my father-in-law complaining that you can’t work on your own car anymore. “It’s all electronics and impossible to get to with an ordinary tool kit.” Things today, especially our much loved tech devices, wear out quickly as if they were designed that way. Economists call that planned obsolescence.

At the risk of appearing sexist (post-Trump political incorrectness is in again) let me show my age and propose a silly comparison to one of my favorite movies. Substitute my hairbrush for “man” and my computer for “woman” and enjoy the lyrics in the clip below.

Here is my story. I’ve been unable to update or add to my blog for the past two weeks. I’ve been the victim of planned obsolescence. I assumed my computer was like my hairbrush but that was foolish and wrong. I see that now. Computers require a lot of fuss (like women) while hairbrushes are, well, like men, just there. I know, I know. Forgive me.

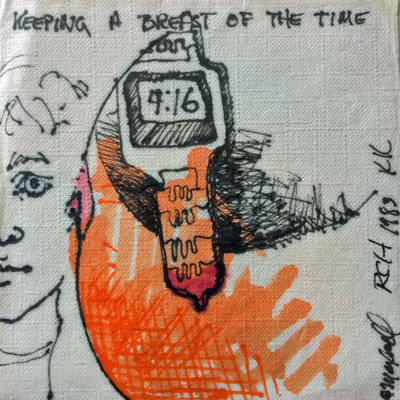

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, James Maxwell and Roy Hoggard artists

One day or another, everyone might find himself confronted with concrete results of planned obsolescence: the inability to fix a broken computer, to replace a broken piece of a washing machine, etc. Consumers often get the impression they don’t control the life-span of the products they buy, and feel trapped in a system in which what’s disposable prevails over what’s repairable. Through this accelerated replacement of goods, we speed up depletion of natural resources, accumulate toxic waste mountains, increase social inequalities and destroy local maintenance and repairment jobs. What should be done then? There are solutions to fight against planned obsolescence at national, European and international levels: public spendings’reorientation, extension of the guarantee system, display of goods’ life span… Above all, it’s a matter of political will and change of mindsets. Thierry Libaert

A change of mindsets puts it mildly. I abhor the downside of our consumer society but the upside is hard to resist. You take the good with the bad I guess. Yet, I do worry sometimes that our fetish for newer and better could make us poorer and worse.

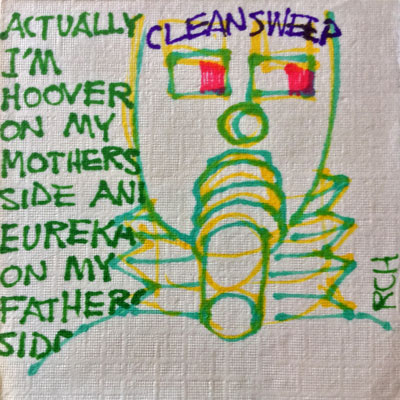

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

The conspiracy theories again abound about ways that older models start to become more unattractive and dysfunctional around the time that a shiny new upgrade is available.

Of course, lots of these signs of “planned obsolescence” have alternative and more benign explanations, related to design, efficiency and innovation. Sure, software upgrades may make older phones run more slowly, but that could be a side effect rather than the primary intention; newer software does more sophisticated stuff (3-D maps! Photo filters! AirDrop!) intended to take advantage of the hardware capabilities of the newest phones, and these more sophisticated features happen to be quite taxing on previous-generation hardware.

In a notable paper from 1986, Jeremy Bulow asserted that a monopolist not threatened by entry would have an incentive to produce goods with “inefficiently short useful lives.” But if consumers have the option to switch to good substitutes — as arguably they do now in the smartphone market — the incentives could run in the opposite direction. Your company might capture a larger share of the market if consumers believe your products are more durable.

“If people are rational and forward-looking and are able to anticipate the shenanigans that company might pull, they will take that into account when buying the thing originally,” said Austan Goolsbee, an economics professor at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business.

The best way to render an older model effectively obsolete is not to make it self-destruct, of course, but to introduce a new product that people really want. The phrase “planned obsolescence” was popularized in the 1950s by the industrial designer Brooks Stevens, who intended it to refer not to building things that deteriorate easily, but “instilling in the buyer the desire to own something a little newer, a little better, a little sooner than is necessary.” Today the term has come to be associated with conspiracies to degrade older products, but in the past it was more closely associated with innovation in new ones. Of course, innovation is expensive, and not easy to come by.

See these essays:

The Way Items Are Designed To Fail

Planned Obsolescence: Competition Against Longeivity

A Phony Business: How Planned Obsolescence is Not Socially Responsible

Here’s The Truth About the Planned Obsolescence of Tech

The libertarian economists seem to always come up with wonderful defenses of capitalism (see Planned Obsolescence Isn’t Really A Problem). Remember the Bill Gates (disputed) quote: “640K ought to be enough for anybody.” Clearly 640K was not enough. Technology and “progress” in general keep marching along. Newer and better has always been the marketer’s mantra especially in the “new world.” After all, none other than the conservative’s darling Ronald Reagan was a spokesman for it.

Yes, the dogs bark but the caravan moves on as they say. I have resolved my immediate problem with modern technology. But, I can’t help but wonder where it all leads. I may not live long enough to find out. Planned obsolescence has me in its sights, all of us in fact. We all wear out eventually. Then, maybe not. It is something the No Planned Obsolescence group is working on.

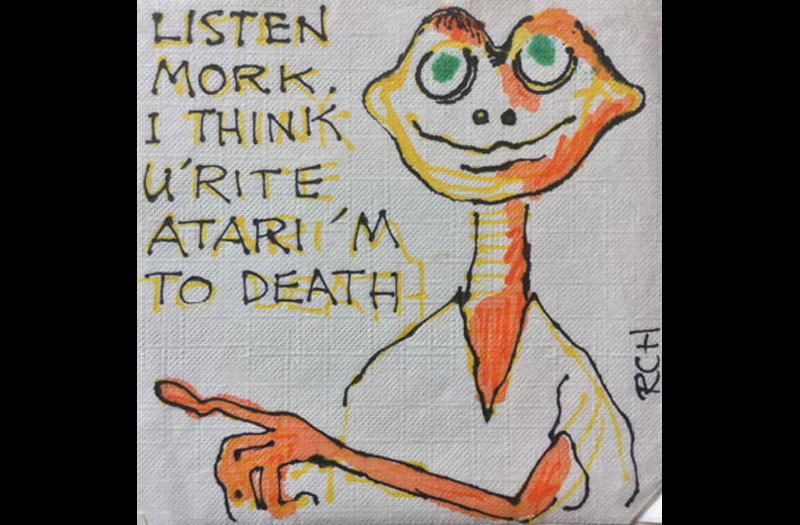

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

My first job was selling FB door-to-door. Some say the hardest job in the world. I was the, or on one of the top salesman, in our area at 16-years old. Have to accept mucho rejection and be resilient. Your brush was one of my favorite items to sell as it was one of the most expensive and we were the minimum wage of $1.65 per hour plus commish. The brush, I recall sold for $9.95 in 1972, or about $60 in 2019 dollars.

Nice story, KD.

P.S. I remember reading in Hedrick Smith’s, The Ruusians, how the Russkies would mock AmeriKa about our products with built in obsolescence, especially automobiles.

https://youtu.be/A7zuMREQleI

Wonder how long Trump Tower Moscow will last?