Bertrand Russell wrote his essay on the benefits of doing nothing in 1932 during the Great Depression which destroyed the jobs and lives of millions. You can read the essay at this LINK or scroll down to the bottom of this post and listen to it.

Russell argues that modern societies glorify work far beyond what is rational or moral, and that genuine human flourishing requires much less labor and far more leisure—not as mere rest but as the condition for culture, creativity, and citizenship.

Russell was an intellectual who paled around with a select group that shared his interests including Virginia Woolf and her husband Leonard, John Maynard Keynes, Vanessa and Clive Bell, Lytton Strachey, Roger Fry, E.M. Forster and others. He was wealthy by birth and later in life although he went through periods of financial strain. His aristocratic background shaped his belief in the value of leisure.

Intellectuals are a distinct minority in America today. Estimates vary from less than 5% to perhaps 15%. Eighty to ninety percent of Americans are culturally discouraged from sustained intellectual development. Intellectuals have always been a distinct minority, but Russell blamed society, not ordinary people. Late in the essay, he writes that workers have never been trainedfor meaningful leisure because society never intended to give them any. For Russell, the lack of leisure skills is not a reason to reject idleness. It is the result of denying it for generations.

Russell wrote “In Praise of Idleness” in 1932, during a moment of global unemployment, technological abundance, social misery, democratic brittleness, and ideological extremism. The essay reflects his belief that machines had created the possibility of universal leisure, the Depression proved the system was irrational, and democracy required citizens with time to think, create, and live fully. In that sense, the essay is both a product of its time and shockingly relevant to today’s AI-driven economy.

Russell saw, long before modern sociologists, that the 19th/20th-century work ethic was not neutral but a cultural weapon used to justify exploitation of the working class, moralizing about the poor, and the idea that human value equals labor output. His ideas are now widely accepted. Russell predicted the paradox that productivity gains would be used to increase output, not reduce working hours, unless society actively chose otherwise.

His principle remains powerful. If machines can do the work, humans should reap the leisure. This is the moral core of many modern UBI arguments (e.g. Andrew Yang).

Russell believed idleness is a precondition for culture and democracy. Philosophy, science, literature, political participation, and creative thought all depend on unhurried time, not endless labor. Russell’s essay is brilliant at connecting leisure with civilization.

Russell points out that much work is useless, some work is harmful, and many jobs exist only to maintain social structures. The idea that not all labor is good remains one of the essay’s most important and prescient insights.

There are, no doubt, valid criticisms, of Russell’s praises for idleness, but I won’t make them. They are embedded in the conventional wisdom of our Affluent Society (as J. K. Galbraith argued.) Great thinkers are meant to shake things up and provide opportunities for change. The Protestant work ethic has been both a feature and a bug of modern capitalist society. Of course no one wants to throw out the baby with the bath water. But, if the bath water is starting to stink, perhaps it’s time to change it.

I myself have opted for a little idleness over the next few days. I’m looking forward to it. Wish me luck.

Best Wishes for a little idleness.

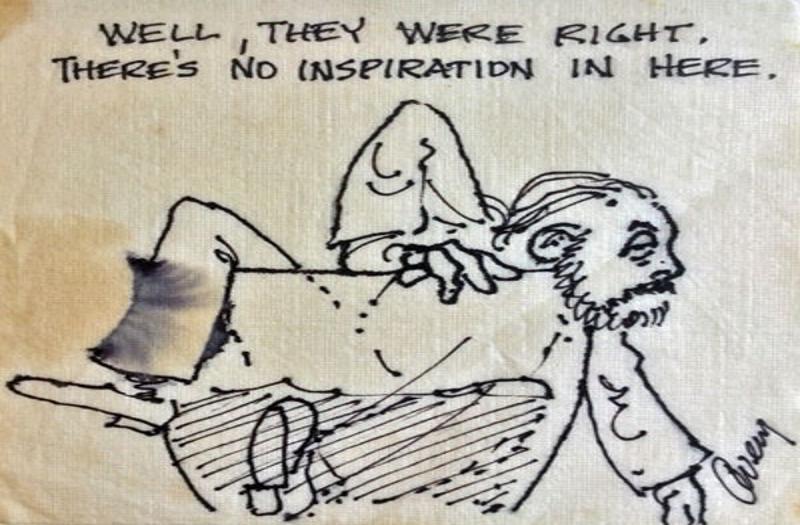

Can I put in for a little intellectualism?

Absolutely! I’ll let you know if I find any.

You’re on!

Many people think being idle isn’t “doing” anything. They’d be surprised at what gets “done”.

I agree with all these points you make… especially the way work in USA is currently contrived to produce, subdue, and keep down a permanent underclass. The present admin seems hell-bent on furthering this pharaohs vs serfs paradigm…