Free will, it’s a bitch. John Milton, The Devil’s Advocate (movie)

I’m no puppeteer … I don’t make things happen. Doesn’t work like that … Free will, it’s like butterfly wings–one touch and it never gets off the ground. I only set the stage; you pull your own strings. John Milton, The Devil’s Advocate (movie)

You are not free – get over yourself. Steven Weinberg

I have a friend who believes that when it comes to death, we all have our names in a big book somewhere and it doesn’t matter what we do, our time of death is fixed. It seems to me this is impossible to disprove since no matter how or when we die one can simply say: “Well, that was the date in the book.” Determinists (including many physicists) have a similar belief: if the universe is constructed entirely of elementary particles that behave according to fixed laws, once the initial conditions are specified the future can unfold only in one way. Authors like Jorge Borges muse about such a deterministic universe. Consider The Library of Babel.

Jorge Luis Borges wrote a delightful story entitled The Library of Babel. The narrator tells us of a gigantic library containing all possible books that could be written using 25 characters: 22 letters of the alphabet plus period, comma, and space. The overwhelming majority of the resulting books is gibberish. A small subset is legible, in one language or another, but describes things that have nothing to do with the real world. And one book — just one, good luck finding it! — describes every aspect of the world, including past, present, and future. Massimo Pigliucci

In a short novel by the Spanish writer/philosopher Miguel de Unamuno (MIST) the principal character, Augusto, who is contemplating suicide confronts the author (Unamuno) near the end of the story.

“The truth is, my dear Augusto”, I spoke to him the softest of tones, “you can’t kill yourself because you are not alive; and you are not alive—or dead either—because you do not exist.”

“I don’t exist! What do you mean by that?”

“No, you do not exist except as a fictitious entity, a character of fiction. My poor Augusto, you are only a product of my imagination and of the imagination of those of my readers who read this story which I have written of your fictitious adventures and misfortunes. You are nothing more than a personage in a novel, or a novice, or whatever you choose to call it. Now, then, you know your secret.”

If one were a religious believer, one might imagine a similar discussion with God. Bertrand Russell uses just such a discussion as the introduction to his essay on A Free Man’s Worship.

To Dr. Faustus in his study Mephistopheles told the history of the Creation, saying:

“The endless praises of the choirs of angels had begun to grow wearisome; for, after all, did he not deserve their praise? Had he not given them endless joy? Would it not be more amusing to obtain undeserved praise, to be worshipped by beings whom he tortured? He smiled inwardly, and resolved that the great drama should be performed.

“For countless ages the hot nebula whirled aimlessly through space. At length it began to take shape, the central mass threw off planets, the planets cooled, boiling seas and burning mountains heaved and tossed, from black masses of cloud hot sheets of rain deluged the barely solid crust. And now the first germ of life grew in the depths of the ocean, and developed rapidly in the fructifying warmth into vast forest trees, huge ferns springing from the damp mould, sea monsters breeding, fighting, devouring, and passing away. And from the monsters, as the play unfolded itself, Man was born, with the power of thought, the knowledge of good and evil, and the cruel thirst for worship. And Man saw that all is passing in this mad, monstrous world, that all is struggling to snatch, at any cost, a few brief moments of life before Death’s inexorable decree. And Man said: `There is a hidden purpose, could we but fathom it, and the purpose is good; for we must reverence something, and in the visible world there is nothing worthy of reverence.’ And Man stood aside from the struggle, resolving that God intended harmony to come out of chaos by human efforts. And when he followed the instincts which God had transmitted to him from his ancestry of beasts of prey, he called it Sin, and asked God to forgive him. But he doubted whether he could be justly forgiven, until he invented a divine Plan by which God’s wrath was to have been appeased. And seeing the present was bad, he made it yet worse, that thereby the future might be better. And he gave God thanks for the strength that enabled him to forgo even the joys that were possible. And God smiled; and when he saw that Man had become perfect in renunciation and worship, he sent another sun through the sky, which crashed into Man’s sun; and all returned again to nebula.

“`Yes,’ he murmured, `it was a good play; I will have it performed again.'”

Having been raised a Catholic (though no longer a believer) with all the guilt and narcissistic angst that implies, I often find myself musing upon existential questions. More sensible people push these unanswerable questions aside while enjoying the benefits of an unexplained life. I am unable to do that. The idea of Fate, the idea of a book with my death date engraved in stone, of a puppeteer that controls my life—such ideas both terrify and intrique me.

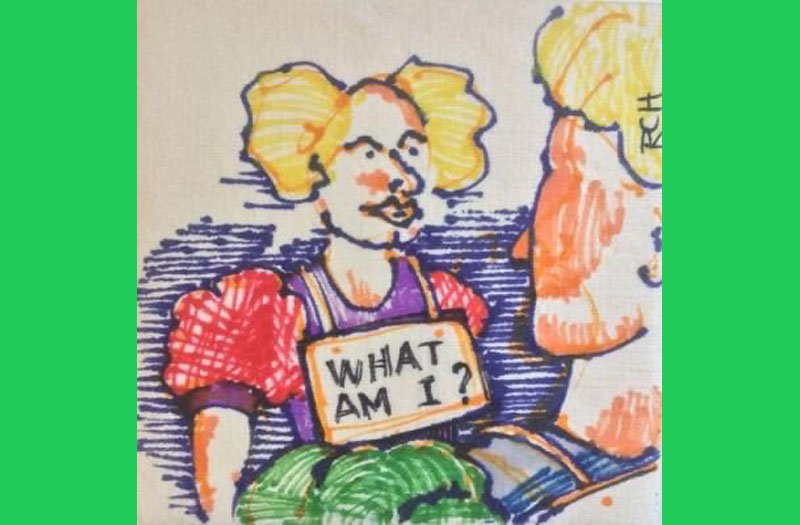

Perhaps you, even if only briefly, do think about questions such as—What am I? What is the meaning of it all? Where does life come from?—and so forth. The Nobel physicist Richard Feynman in his 1998 book The Meaning of It All provide the answer: “We don’t know.”

What, then, is the meaning of it all? What can we say today to dispel the mystery of existence? If we take everything into account, not only what the ancients knew, but also all those things that we have found out up to today that they didn’t know, then I think that we must frankly admit that we do not know. But I think that in admitting this we have probably found the open channel.

That we do not know the answer to such questions can be uncomfortable. At worst it can leave us incapacitated and hopeless. No wonder so many people ignore such questions and get on with their lives. What about those of us who can’t do that? Albert Camus offers his best idea of how to live with the unsettling fact that there are things we simply don’t know and may never know in The Myth of Sisyphus.

Man stands face to face with the irrational. He feels within him his longing for happiness and for reason. The absurd is born of this confrontation between the human need and the unreasonable silence of the world.

How can we live with the “absurdity” of life as described by Camus? Camus offers three choices: give up (suicide), adopt a false framework such as religion, or accept that true meaning is impossible to find and live on in rebellion. Camus chooses the third choice—live on despite the bleakness of reality in beautiful defiance of it. (paraphrase of Daniel Miessler, see below)

I leave Sisyphus at the foot of the mountain! One always finds one’s burden again. But Sisyphus teaches the higher fidelity that negates the gods and raises rocks. He too concludes that all is well. This universe henceforth without a master seems to him neither sterile nor futile. Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of that night-filled mountain, in itself forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy. The Myth of Sisyphus

Massimo Pigliucci in an essay on free will summarizes three basic stances:

Hard determinism takes for granted that the universe is a deterministic system, and therefore rejects the notion of free will, because it takes the latter to mean that human beings can make decisions that are somehow disconnected from the normal web of cause-effect (which, for all effective purposes, would make any instance of true free will a miracle.

Compatibilists also think that the universe is deterministic, but go on to articulate a number of senses in which we have “free” will, though not in the contra-causal sense explained just above. For instance, they may say that I am “free” to raise my arm just in case nobody has tied me up or is otherwise hindering my decision to raise the arm.

Libertarians believe in contra-causal free will, and therefore reject the notion of determinism. Many libertarians are Christian theologians, who need that notion in order to articulate the so-called “free will defense” against the possibility that God is not all-powerful, or all-knowing, or all-good.

So, where does this leave my friend who believes our death date is indelibly inscribed in a book? He is a determinist as defined above. It is an eminently defensible position given all that we know from modern physics.

The usual argument against free will is straightforward: We are made of atoms, and those atoms follow the patterns we refer to as the laws of physics. These laws serve to completely describe the evolution of a system, without any influences from outside the atomic description. If information is conserved through time, the entire future of the universe is already written, even if we don’t know it yet. Quantum mechanics predicts our future in terms of probabilities rather than certainties, but those probabilities themselves are absolutely fixed by the state of the universe right now. A quantum version of Laplace’s Demon could say with confidence what the probability of every future history will be, and no amount of human volition would be able to change it. There is no room for human choice, so there is no such thing as free will. We are just material objects who obey the laws of nature. Sean Carroll, The Big Picture

Yet Sean Carroll, quoted above, describes himself as a compatibilist. That is, he accepts the laws of physics and agrees that they fully determine the future but he finds a place for a sort of free will in the world of human beings.

Of course there is no such notion as free will when we are choosing to describe human beings as collections of atoms or as a quantum wave function. But that says nothing about whether the concept nevertheless plays a useful role when we choose to describe human beings as people. Indeed, it pretty clearly does play a useful role. Sean Carroll

The question that arises here is how “to describe human beings”—as collections of atoms or as people and if as people what exactly do we mean by people? A religious person might say people are individual spiritual entities. But, Sean Carrol would not agree. What Sean Carroll seems to be getting at is that as a practical matter we must assume free will of a certain sort to get on with our lives. But what actually are these lives?

These are what philosophers sometimes call the “hard” questions.

As someone who respects science, I am partial to determinism. Like Camus, I find myself “face to face with the irrational.” If we are ultimately no more (and no less) than a particular bundle of atoms, where does life, consciousness, identity, purpose and free will come from if they exist? Are they illusions? Or are they some kind of emergent conditions that atoms get themselves into?

I wish I knew but as Feynman says: “We don’t know.” Our death date may be inscribed in a book somewhere, maybe in the Library of Babel, but that book is not accessible to us, not yet. In the meantime we don’t have to act stupidly by ignoring the world around us by, for example, not wearing a mask. In fact, only by paying close attention to the world around us can we increase what we do know.

I recently read an article by Daniel Miessler, Free Will And The Absurdist Chasm, that I found randomly while researching this post. I know nothing about Mr. Miessler but I think he hits the nail on the head. He says:

I say that we are ok to embrace certain structures and frameworks, whether traditional or created on your own, as long as they are not harmful and as long as people know they are false. I believe Camus warned against believing these systems are true, not against using them.

We have a structure given to us by evolution, and combined with our strange and limited interfaces to the natural world they make up our unique, human set of values and goals. Love, respect, responsibility, etc.

He describes what I mean by “some kind of emergent conditions that atoms get themselves into.”

So there you have it, my take on Fate and Free Will at this point in time.

I must end with my favorite answer to “What am I?” by Bill Bryson from his book A Short History of Almost Everything

Welcome. And congratulations. I am delighted that you could make it. Getting here wasn’t easy, I know. In fact, I suspect it was a little tougher than you realize.

To begin with, for you to be here now trillions of drifting atoms had somehow to assemble in an intricate and intriguingly obliging manner to create you. It’s an arrangement so specialized and particular that it has never been tried before and will only exist this once. For the next many years (we hope) these tiny particles will uncomplainingly engage in all the billions of deft, cooperative efforts necessary to keep you intact and let you experience the supremely agreeable but generally underappreciated state known as existence.

Why atoms take this trouble is a bit of a puzzle. Being you is not a gratifying experience at the atomic level. For all their devoted attention, your atoms don’t actually care about you-indeed, don’t even know that you are there. They don’t even know that they are there. They are mindless particles, after all, and not even themselves alive. (It is a slightly arresting notion that if you were to pick yourself apart with tweezers, one atom at a time, you would produce a mound of fine atomic dust, none of which had ever been alive but all of which had once been you.) Yet somehow for the period of your existence they will answer to a single overarching impulse: to keep you you.

The bad news is that atoms are fickle and their time of devotion is fleeting-fleeting indeed. Even a long human life adds up to only about 650,000 hours. And when that modest milestone flashes past, or at some other point thereabouts, for reasons unknown your atoms will shut you down, silently disassemble, and go off to be other things. And that’s it for you.

RELATED POSTS

The Attic – Where Artists and Browsers Can Meet

Short Fiction – Cado Maestro Tiene Su Librito (Every Teacher Has His Little Book)

Imagination and Reason in the Time of Tragedy: Lao Tzu, Voltaire, Blake, Camus, and Marquez