The tasty apples that gave rise to the phrase “as American as apple pie” aren’t native to North America. The seeds journeyed over from Europe like illegal aliens. The spices, cinnamon, nutmeg and clove, sneaked in from Asia via the European spice trade. After years of grafting and careful cultivating, the apples we take for granted today were eventually perfected and carried across America with waves of pioneers heading West. The first American cookbook, American Cookery by Amelia Simmons published in 1796, included two apple pie recipes.

During World War II, American soldiers famously said they were fighting for “mom and apple pie.” Suddenly, the humble dessert became shorthand for all things wholesome and patriotic.

After a disastrous fire some fifty years ago, I rebuilt the Sea Gull Restaurant and relocated the “Cellar Bar” upstairs. James Maxwell, local artist, offered to paint a new Pied Piper to replace the one that burned in the fire. He used local children and town characters in the scene which we hung above the entrance to the “new” bar. The painting was so popular I commissioned Max to do a series of large fairy tale paintings to hang on the ceiling between the rough hewn beams.

Max’s rendition of Johnny Appleseed was one of the last paintings.

“Johnny Appleseed is us,” said Max in a piece he wrote about the painting. Excerpts from notes he wrote about the process of choosing Johnny Appleseed for one of the final paintings are in italics below.

The Pied Piper was German, maybe Polish, possibly Eastern-European. Hamlin must have been the center of that particular plague. The Princess and the Pea, that was created out of the French love of farce. Rapunzel was from eastern Europe and the brothers Grimm’s’ research into ancient tales. Stone towers were commonplace during the dark ages. Our Jack and the Beanstalk was from the English court’s satire on their war with Spain. Rumpelstiltskin came from ancient cultures, as the very rich at the time were the only ones who profited from bloodlines for their children were bargaining chips. And Lolli (local textile artist) had told me it was pre-Egyptian because of the spinning wheel. The following canvas inspired by archetypes from the age of chivalry repressed Catholic Europe, but my St. Dragon and George’s free-love inspired hippie movement. Beauty and the Beast came from France. With symbolism and drama from their stage that was over the top emotionally. Midsummer Night’s Dream was from the 16th-century English stage, by Shakespeare …

I looked deeper into the sequence of the fairy tales I painted. They were from Europe or the Near East. Our ancestors brought them to share culture, wisdom, intelligence, and to remember their ancestral homes …

Where in America did we have examples of our fairy tales? Those I found were legendary stories of real people, stories told about events that had happened to pioneers, then embellished for entertainment. Some were not quite yet evolved enough to be moral lessons, or have themes of the human condition. Like Pecos

Bill, they were entertaining. I didn’t want mine to be like Disney.

Also, tales of Americana were passed down by poets in their songs or by spoken stories. To do the real work, I had to choose two stories, one inspired by American culture moving West and one belonging to Native Americans.

David’s commission allotted for only three more slots between the beams of the Sea Gull. Rather than innocently plowing ahead, I had to commit to myself three paintings before I put brush to canvas. As you can tell, I was limited in my choices because I knew that sooner or later I would have to paint the whole town, and that would have to be Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves. That Far Eastern story could contain the most people. I heard it loud and clear that lots of folks wanted to be in the paintings.

American tales are about the individual; George Washington and the cherry tree, Dangerous Dan McGrew, Pocahontas, George Washington throwing the coin across the Potomac. What stopped me from picking any of these was that they struck me as poses, cartoon-like images. When I remembered a story, from my history lessons, of Johnny Appleseed, the choice for an immigrant tale was natural, from the East to West in ongoing time. Hey! That works. That is us; Johnny Appleseed is us.

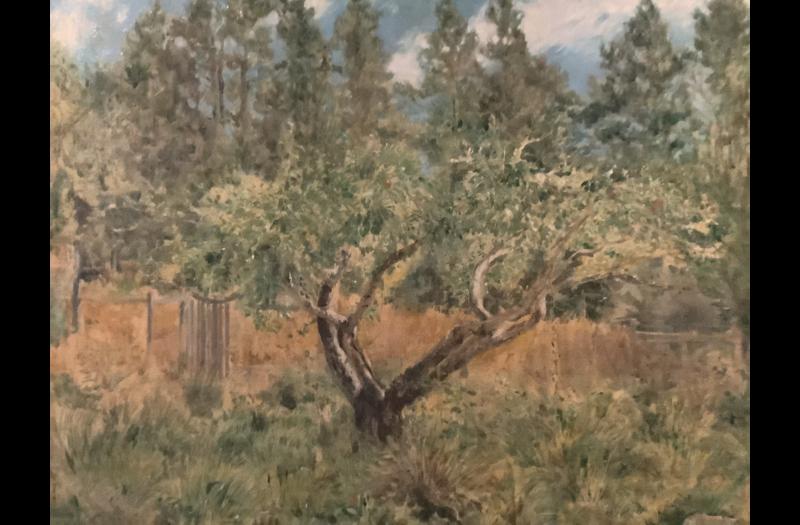

Easy for me as I lived in an apple orchard. Johnny Appleseed inspired me as the singular American altruism. He was a flesh and blood person who followed his dream, from youth to older man. (I know, I know, some say he was a real estate developer, some saw him as a dirty-old-man giving apples to children as victims. I even heard he embodied the role to stake claims on land for shadowy investors.)

I wanted to believe the real Johnny Appleseed made it possible for countless people moving west to have a decent food supply: he contributed by apples, to wagon trains as he marked his path. What a guy! Mom and apple pie! He made it possible for pioneers to have applejack whiskey, a real hero to people living that

hard life. I eat apples daily. The downside, the story had only one character. I added butterflies and sheep on the landscape of our home. Johnny had to be the right story to paint next. Curiously what made it fit into my body of work was the only tale about one person. Every other tale told of conflict, flesh, and blood, hardship, loneliness, the confusion of relationships. And with this painting, including Johnny Appleseed, it is about one man’s contribution.

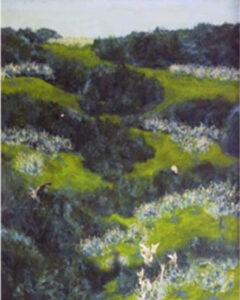

When I got down to it, the painting had to be about celebrating spring, being comfortable with nature, at home, being safe, being on the right path for who you are, and knowing it. It wasn’t about rugged individualism; it was about being present. To do your life’s work, knowing that to be alone much of the time is OK. That taking a deep breath is as good as any prayer. That maybe life as we know it is OK. If we keep our eyes open and let ourselves be part of the landscape, perhaps we can accept all that is.

So, being delighted to be in the light of early morning, to feel the chill of the air, wet grass, abundant apples, and knowing you are nature. I sensed the meaning to the painting was like me, the right kind of victim-of-life like everybody else here. Here for just a moment, free from violence for a time, breathing without fear, without looking over our shoulders for impending danger. Knowing we are not responsible for all the world’s problems, and given half a chance, we may be Mr. Appleseed.

Location, location, location, this spot along the road is real. It exists, I sketched out the composition sitting there. Looking south up the hill, it no more than a quarter-mile to Orr Hot Springs’ cabins and spa, and a half-mile to Montgomery Woods State Park, home to the most towering redwoods in our county. Sheep and eagles, spring and blossoming fruit trees, every year from their planting in the 1850s. The right spot for Johnny to kneel and plant another tree.

I decided to paint Johnny shoring up a sapling. I chose the simplest of light around 9 in the morning. It spoke of the beginning of a work-day. It set my pallet of colors to be limited. The degrees of contrast would soften as we looked past the man, the sheep, and the wing’s eagle. The apples provided a color contrast, but David’s (David Onstandt who drove truck for a local specialty food outlet) face, hands, and foot told the day’s temperature. The grasses in the patchwork of meadows deepen the farther up the hill. In the early morning, sometimes, the gray of a tree’s bark takes on the color blue, and we believe that to be true.

The Apple’s Complicated History

Apples are found in Greek, Norse, and Celtic myths with a variety of different meanings. They may provoke rivalry, erotic desire, or irreversible choice. Apples are not an innocent fruit. In Norse mythology the golden apples of the goddess Idun prevent the gods from aging. When the apples are stolen, the gods grow old and weak. In the Celtic legend of Avalon (The Isle of Apples) the apple represents the door between life and death. In the Biblical chapter of Genesis the apple is not specifically mentioned as the forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden but it became associated with evil through a quirk of language. In Latin mălum (with a short ‘a’) is evil whereas mālum (with a long ‘a’) is apple. By the Middle Ages the apple had become the fruit of knowledge, the price of sexual awakening, and the moment innocence collapses into history. It is the object you touch when you choose to know too much. No wonder the apple has become such a common symbol in art, poetry and literature. A few examples show some of the many ways apple symbolism has been used.

In Chekhov’s Little Apples a tiny act of kindness momentarily warms a life but that life remains fundamentally unchanged. The moral: while a simple act of kindness can be powerful and priceless, it can also leave the inequities of life fundamentally unchanged. Katherine Mansfield’s The Apple Tree shows how life can be a disappointment once expectations have been set high, how false hope can be undermined by the harsh reality of life. In The Apple Tree Daphne du Maurier writes about an apple tree that turns into a force of darkness. While Chekhov and Mansfield explore blindness, belated lucidity, and quiet moral failure, Du Maurier asks an even more disturbing question: what if lucidity doesn’t just arrive too late but actively turns into cruelty? Clearly there are more things in heaven and earth than exist in Johnny Appleseed’s simple pastoral world. William Blake warned us a couple of centuries ago that the apple is not as simple as it seems in The Poison Tree.

We can only pilfer from the top of the barrel in a short blog but in addition to the short stories mentioned there are three novels that come to mind as I write this paean to the apple. In American Pastoral Philip Roth takes up the theme of Milton’s Paradise Lost where the apple has a cluster of meanings: a shorthand for pastoral innocence, earned prosperity, and the fantasy of moral simplicity the novel methodically dismantles. Johnny Appleseed makes a short nostalgic appearance in the novel. The Johnny Appleseed passage symbolizes the American belief that goodness, cultivation, and decency can shield a private life from history. The novel exists to show why that belief is tragically false.

At The Edge Of The Orchard by Tracy Chevalier is a novel that historicizes several apple themes. It shows how blindness to the ordinary, delayed recognition, and moral damage are not just psychological states but inheritances passed through families and landscapes. Blindness to the ordinary can become a lifestyle. Poisoned apples can become landscapes. Failure of attention can echo across generations. Lucidity is not only belated, it is often absent. Chevalier gives us the orchard that keeps growing long after anyone is watching.

I would never have expected to read a novel about a young girl coming of age on an apple farm in rural southern Wisconsin. But, The Excellent Lombards by Jane Hamilton is not only laugh out loud funny but also existentially moving. What if lucidity never arrives, not because people are cruel or naive, but because they are emotionally incapacitated by love, fear, and habit? The novel shows how goodness itself, love, loyalty, and care, can become a form of blindness, delaying lucidity not through denial or malice but through the fear that seeing clearly might wound the very people one is trying to protect.

Contrary to the biblical warning against it, eating an apple a day may be a good thing. Or not. There is plenty of art, poetry, and literature however that can’t hurt you and may well inspire you in a way that life without apples couldn’t. If nothing else, reading is a proven cure for insomniacs. So, read away on all the apple related stories out there.

After Apple Picking by Robert Frost is a poem that captures the felt experience of belated lucidity: not sudden insight, not crushing guilt, not violent refusal or any of the other emotions and thoughts the apple brings to mind but the quiet, ambiguous exhaustion of a mind that has handled too many ordinary moments to sort them cleanly anymore.

Nice work…

Thank you.David

Very good, as always.