[Click on BLUE links for sources and information]

Many years ago in one of my first college economics classes the professor speculated that cash would soon become a thing of the past. The developed world and the United States were moving, in his view, inexorably toward a cashless economy. Credit cards made their debut in the 1950s and by the 1960s American Express advertisements were ubiquitous: “American Express, it’s the only credit card you really need for travel and entertainment worldwide.”

Well, that was over fifty years ago and while we use less cash than we used to, “about 70 percent of Americans still use paper money on a weekly basis.” U. S. dollars in circulation (i. e. paper money and coin) as a share of GDP has actually been growing lately from about 6% in 2010 to 9% in 2018. We are not yet a cashless society, not by a long shot. Along the way, the one hundred dollar bill has become the most popular currency beating out the one dollar bill in 2017.

According to a recent report from the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, the $100 bill is on the rise as a form of savings. With low inflation and a financial crisis still relatively fresh in people’s memories, more savers than ever are choosing to keep some of their wealth in large-denomination banknotes. And it’s not just Americans. The Fed researchers suggest that people across the world are stashing hundreds under their beds as an alternative in case their local currency takes a dive.

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Sandra Lindstrom artist

One of the largest fans of phasing out cash is economist Kenneth Rogoff. He wrote a book about the subject, The Curse of Cash. Rogoff summarized his reasons in a recent NPR interview: “ Well, what I object to is people buying apartments in Trump Tower with suitcases of cash, buying $50,000 cars, engaged, of course, in drug transactions, human trafficking, whatever. A lot of people have perfectly healthy, good uses for cash. I have no moral objections to it. And I think for small transactions, it’s still a big deal.”

[Note: For a scholarly critical review of The Curse of Cash, try The War On Cash by Jeffrey Rogers Hummel]

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

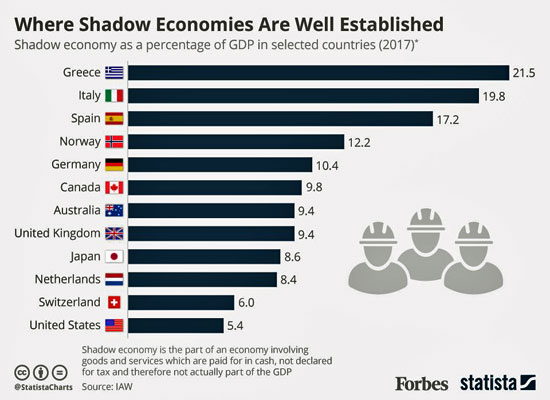

There is no doubt cash facilitates what economists call the “underground” or “dark” economy. There are obvious reasons why. There is no record of cash transactions. If you want to avoid taxes or engage in illegal activities such as drug dealing or prostitution or avoid sanctions on arms deals and so on, cash is the preferred way to do business. As a financial advisor I occasionally had a client come in with cash to invest. I didn’t ask questions but told them I could not invest cash.

There are disadvantages to a cashless society. How, for example, do you give a server a tip? While more and more people, especially younger people, have access to Venmo, PayPal, Zelle or similar apps, what about those who don’t? Many lack bank accounts, including low-income families deterred by fees and minimum balance requirements. (A report by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation in 2017 estimated that 6.5 percent of American households were “unbanked.”) Older adults also may not have electronic payments set up, or be comfortable using them. There are legitimate concerns about privacy and data security.

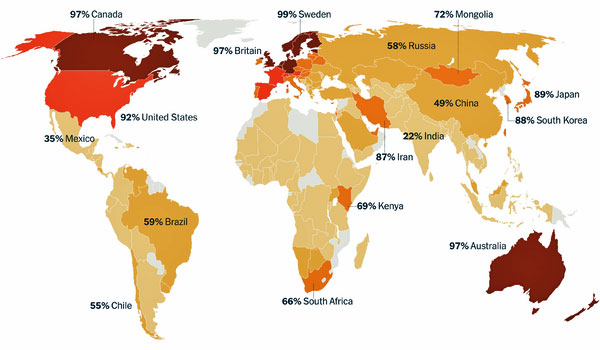

Share of adults who made or received any non cash payment, New York Times and The World Bank, McKinsey & Co.

Some of the benefits and disadvantages are summarized in a recent article in The Balance:

Benefits

- Lower crime because there’s no tangible money to steal

- Less money laundering because there’s always a paper trail

- Less time and costs associated with handling paper money as well as storing and depositing it

- Easier currency exchange while traveling internationally

Disadvantages

- Exposes your personal information to a possible data breach

- If hackers drain your bank account, you’ll have no alternative source of money

- Technology problems can leave you with no access to your money

- The poor and those without bank accounts will have difficulty paying and receiving payments

- Some may find it harder to control spending when they don’t see physical cash leaving their hands

- Banks may start charging fees to compensate for possible negative interest rates

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Artist Unknown

Portability and control are very important to some people. I discovered this as a financial advisor when I realized that a few of my clients had memories of having to quickly leave their homes, businesses and even their country for political reasons. Cash, gold and jewelry were among the few items of value they could carry with them. I had one client who had a great fear of not having money when she needed it. She would stuff cash in various books on her bookshelves where she could retrieve it in an emergency. She kept this habit to herself. When she passed away, family members were surprised when they found twenty, fifty and even hundred dollar bills as they went through her books to organize them for a garage sale.

There is a comfort in cash when the economy goes into a tailspin. While few alive today remember the Great Depression, many remember the stories about banks that failed and tied up customer money indefinitely. I noticed that my older clients liked to hold their securities in paper form rather than electronically and they put aside piles of cash in books or safes or in some cases hidden in cans in the back yard. A few years ago there was even a story of a man who had nearly half a million dollars in the trunk of his car. In a cashless society none of this would be possible.

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

Sweden has made the largest transition to a cashless society. Only about 15 percent of retail sales in Sweden are made with cash. There are many “no cash accepted” establishments and some banks no longer handle cash. China and even India are moving in the same direction. There are already some shops and restaurants in the United States that have instituted cash-free policies — some in just one location, some in many or all — include Starbucks, Dig Inn, Dos Toros, Sweetgreen and Argo Tea. In-flight purchases on airplanes have been cash-free for a long time, and some government offices do not accept cash.

It has taken fifty years but my professor’s speculation seems to finally be coming around. Credit card companies and banks are happy. Others are not convinced. Regardless of which side you come down on, you should understand the benefits and disadvantages and prepare yourself for what seems much closer now than it did fifty years ago when I first heard about it. Habits are slow to change but there may come a time when we have little or no choice. Then again, maybe we’ve got another fifty years to go.

For several years I hosted a financial radio show on KMFB called MONEY TALKS. The theme song, Money’s Too Tight, seems like an appropriate way to end this post.

A 2018 research paper from the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago estimates that 60 percent of all U.S. bills and almost 80 percent of all $100 bills are now overseas. That amount is up from 15 to 30 percent around 1980, according to research from Federal Reserve Board economist Ruth Judson. She found that economic and political instability contribute to this demand.

https://www.msn.com/en-us/money/markets/theres-been-a-mysterious-surge-in-dollar100-bills-in-circulation/ar-BBU9tXu

Other 20 percent circulates in downtown Mendocino…

Sorry David,

That ain’t my coin.

I saw what I thought was a JM. I’ll change it. Thanks. Lots of napkins were hard to identify.

The problem with a cashless society is that while it may deter organized crime and

money laundering operations, it also allows for absolute top down control of the money

supply. An underground economy is a way for the citizens to have some control of their

lives in spite of tyrannical or authoritarian control. When people have money, they have a modicum of personal power and choice; without access to money we are prisoners. The “New World Order” has been planning on eliminating cash for a long time. The Bitcoin experience is an experiment to see if people go for it, and to prepare

them for the pending loss of their freedom.

I agree but the bitcoin experiment has not gone well. I doubt that cash will disappear but it is definitely shrinking relative to credit/debit cards mostly as online purchases replace brick and mortar. Like it or not technology is taking over. But there is a valid and growing movement against this. One example is Jenny Odell’s How to do Nothing.