“My predominant feeling is one of gratitude. I have loved and been loved. I have been given much and I have given something in return. Above all, I have been a sentient being, a thinking animal, on this beautiful planet, and that in itself has been an enormous privilege and adventure.” Oliver Sacks, Gratitude

Living is the one great artistic endeavor into which we are forced through no choice of our own. Camus was right when he said that judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy. If you choose life, you’re not off the hook. Now you have innumerable choices to make—which life, how to pursue it and so on—questions with no easy answers. How to live is the constant preoccupation of any sentient human being.

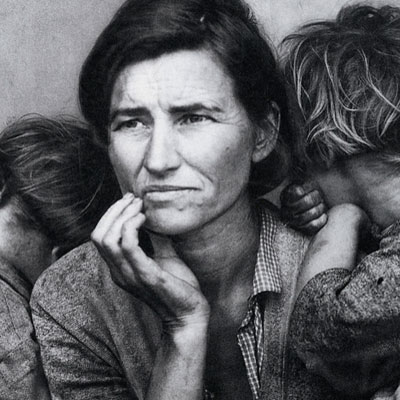

The great American photographer, Dorothea Lange, was told to choose a practical career so that she could have something to fall back on if her venture into photography failed. According to one of her many biographers, she “knew it was dangerous to have something to fall back on.” She feared that if she opted for financial security, she might never be a photographer. The risks she took were great. Some decisions were hard especially for her family, her children. But, the rewards were great. The safe way is not always the best way. On the other hand, few of us are likely to match Dorothea Lange’s genius. We probably should have something to fall back on, but that doesn’t mean we can’t dream and pursue those dreams throughout our lives.

The safe way has benefits, comfort and security, but these are never certain. Ultimately we have to choose the right mix in this artistic endeavor of life without knowing the ultimate results, the medium in which we will work, the pigments or clays, the instruments, the words that we will use, career, family, all of it. These choices must be rational if we are to survive but they should also be organic and imaginative if we are to have feelings of worth. To make choices is why we’ve been put into this ridiculous, or as Camus would say absurd, world where we live. At least that’s what I’ve come to think.

We make our choices through some random mix of genetic inheritance, environment, historical circumstance, habit and pure serendipity.

Napkin Art, Sea Gull Cellar Bar, artist unknown

A life without some risk is not worth living to paraphrase Socrates. Risk and reward are most often in opposition. The reward for a riskless choice may be infinitely small while a high risk sometimes results high rewards but the guarantees are weak. What seems to matter is that we put in just enough effort to make a good choice without stressing over whether it’s a good choice. The philosopher Walter Kaufmann in The Faith of a Heretic says “The question confronting me is not, except perhaps in idle moments, what part might be more amusing, but what I wish to make of my part. And what I want to do and would advise others to do is to make the most of it: put into it all you have got, and live and, if possible, die with some measure of nobility.”

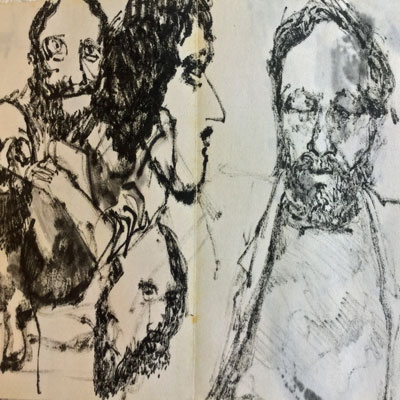

Charcoal Drawing at the Sea Gull Restaurant, Kent Chapman, circa 1968

When big things go wrong, people can be gripped by fear. When you’re on easy street greed can take over. It’s hard not to get distracted. Greed and fear are powerful emotions, fear more so than greed if the researchers are to be trusted. An unexpected schadenfreude may overtake us as we watch others struggle with defeat, but our ill-founded glee is soon followed by a mind numbing terror as we realize that we ourselves could be in jeopardy. No one is immune. Even the most rational people are reduced to a jumble of emotions in trying times—“the heart has its reasons of which reason knows nothing of.” During the last financial collapse, Nobel economist Paul Krugman remarked : “As a professional economist I am fascinated. As a citizen I am terrified.”

Napkin Art, Sea Gull Cellar Bar, Roy Hoggard artist

Sooner or later, difficult times will arise. Will you be ready and able to get through them? George Kinder, author of The Seven Stages of Money Maturity, suggests thinking about three hypothetical questions as a sort of preparation for difficult times.

First, suppose you had all the money you needed and an adequate income for the rest of your life. What would you do with your money? How would you live your life? Just answering this question can change the way you think. Most of us worry about not having enough money but we often give little thought to what we would do if we had more than enough. The monetary constraints and restrictions that can make us feel as if we are not in control, can also add structure to our lives. Without that structure we might find ourselves adrift. Thinking about what you would do if you could do anything is both sobering and empowering. There are more important things in life than money. We all know this instinctively. But, it’s easy to lose track of that fact especially in times of financial crisis. This first scenario can help you focus on what really matters—not the money but what you do with it.

Now, imagine that you had just a few more years to live. Your doctor gives you five to ten years. The upside is that you will have no symptoms but feel perfectly healthy. The downside is that there will be no warning—you will simply die suddenly and without warning when the time comes. Given that you will be dying sooner than expected, how would you change your life? What would you do with your time? You still have several years to live but your time is limited. For many, this scenario can reduce money to an even lower level of importance. With just a few years, you might want to focus on family relationships, artistic endeavors, travel, or planning a personal legacy. It’s doubtful you would focus on stock market returns or how much money you could make in the few years you have left.

Finally, suppose you had only 24 hours to live. What have you missed in life? Who did you not get to be? What did you not get to do? If you can truly experience such a thing, it’s likely your most important regrets would have little to do with the money you have in the bank or the income you can earn or the value of your investments.

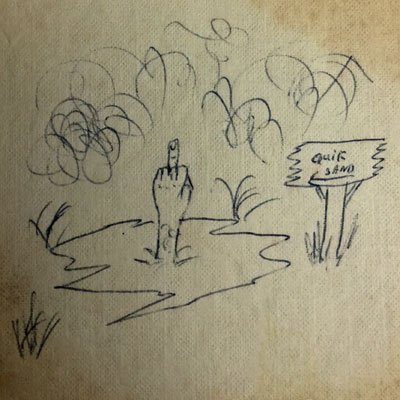

Napkin Art, Sea Gull Cellar Bar, artist unknown

In difficult times, it’s natural to be fearful, angry, depressed. But, remember, every crisis eventually ends. If you can step back and get some perspective before the crisis occurs, you may be able to focus on what’s really important. You will be better prepared to weather the storm and express a little gratitude for a life that’s ridiculous and absurd and full of risks, some worth taking.

Napkin Art, Sea Gull Cellar Bar, Roy Hoggard artist

Nice, King David. Soothing to soul as my dad died 20 years ago today. Died suddenly of heart attack on Berkeley campus, which he loved. Never had time to say good bye or heal old wounds. Cheers, my friend.