[Click on BLUE link for sources and more information]

When men by way of their conventions have got themselves into difficulties, then let the monkey in, he will find the unattainable solution.

Isak Dinesen, The Monkey

I’m old-fashioned and think that reading books is the most glorious pastime that humankind has yet devised. Homo Ludens dances, sings, produces meaningful gestures, strikes poses, dresses up, revels, and performs elaborate rituals. I don’t wish to diminish the significance of these distractions—without them human life would pass in unimaginable monotony and, possibly, dispersion and defeat. But these are group activities, above which drifts a more or less perceptible whiff of collective gymnastics. Homo Ludens with a book is free. At least as free as he’s capable of being. He himself makes up the rules of the game, which are subject only to his own curiosity. He’s permitted to read intelligent books, from which he will benefit, as well as stupid ones, from which he may also learn something. He can stop before finishing one book, if he wishes, while starting another at the end and working his way back to the beginning. He may laugh in the wrong places or stop short at words that he’ll keep for a lifetime. And, finally, he’s free—and no other hobby can promise this—to eavesdrop on Montaigne’s arguments or take a quick dip in the Mesozoic.

Wislawa Szymborska, Nonrequired Reading

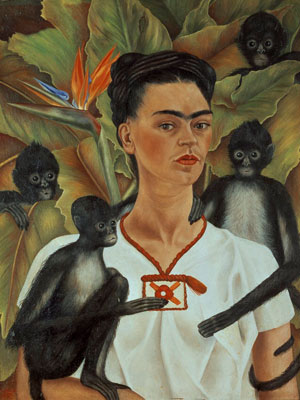

I don’t paint nightmares. I paint my own reality.

Frida Kahlo

Three women, an artist, an author, a poet, a Mexican, a Dane, a Pole, Frida Kahlo (1907-1954), Isak Dinesen (1885-1962), Wislawa Szymborska (1923-2012). What do they have in common? Art, pain, genius and … monkeys. Monkeys? Yes. Frida Kahlo lived with them and painted them.

Frida Kahlo

A favorite poem by Wislawa Szykmborska, Brueghel’s Two Monkeys, demonstrates a principle that Isak Dinesen wrote about in one of her most famous tales, The Monkey: When human relations become unusually complicated or completely mixed up, let the monkey come.

Frida Kahlo Blue House, Cayoacan, Mexico

Brueghel’s Two Monkeys

This is what I see in my dreams about

final exams:

two monkeys, chained to the floor, sit on

the windowsill,

the sky behind them flutters,

the sea is taking its bath.

The exam is History of Mankind.

I stammer and hedge.

One monkey stares and listens with

mocking disdain,

the other seems to be dreaming away—

but when it’s clear I don’t know what to

say

he prompts me with a gentle

clinking of his chain.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

A final exam on the History of Mankind sounds like something we can never complete. Not in this life anyway. If there is an ultimate truth, the search requires imagination and a willingness to take risk. These three women exhibited both in addition to a genius that sets them apart. Isak Dinesen and Frida Kahlo were physically stunning and enjoyed the limelight. Wislawa Szymborska was neither (yet she was once called “the Greta Garbo of World Poetry”. It has been said that Isak Dinesen was “saved from vanity by her wit.” Frida Kahlo explained that “I paint self portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best.” Wislawa Szymborska was “modest and introverted by nature, so much so that she stopped writing poetry for two years after winning the Nobel Prize to avoid the spotlight.”

”Oddly, the work of both Dinesen and Kahlo was initially ignored after their deaths although both later experienced a popular revival, especially Frida. It’s too soon to make that judgment about Szymborska. While her output of poetry is small (some 400 poems in all), the appeal is wide and I suspect her ultimate impact will be substantial.

In an article on Dinesen, Margaret Attwood describes the ghost-like appearance of the writer as follows:

To my young eyes, this person in the pictures was like a magical creature from a fairytale: an impossibly aged woman, a thousand years old at least. Her outfits were striking and the makeup of the era had been carefully applied, but the effect was carnivalesque – like a dressed-up Mexican skeleton. Her expression, however, was bright-eyed and ironic: she seemed to be enjoying the show-stopping, if not grotesque, impression she was making.

The truth of this description is borne out in a picture taken at a legendary luncheon with Carson McCullers, Isak Dinesen, and Marilyn Monroe. Aside from appearing “like a dressed-up Mexican skeleton,” there is another link between Isak Dinesen and Frida Kahlo—both were in their own way fans of the magical realism so popular in Latin American literature. Once seduced by socialist realism, Szymborska became more of a realist, a dark comic of sorts, whose poems were designed “to create a poetic state in her readers, but also to tell them things they didn’t know before of never got around to thinking about.”

Marilyn Monroe, Isak Dinesen, Carson McCullers

So, why am I writing about these three wonderful women other than the fact that I admire and envy them and get so much personal enjoyment out of their work? Monkeys. Yep, monkeys.

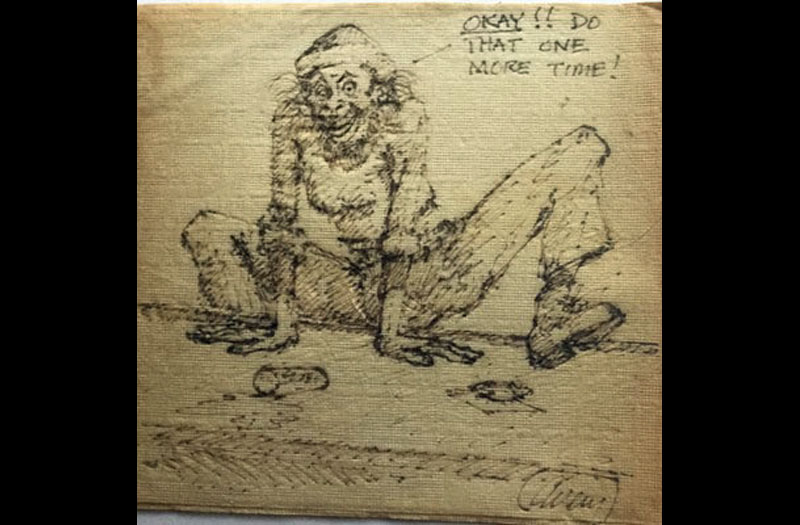

I have noticed that among the seven or eight hundred pieces of Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art that I’ve managed to acquire or photograph there are no monkeys. None. Nada. (Well, maybe one depending on how you interpret the Bob Avery piece that is at the top of this post.) I do find that a bit strange. After all, there are dozens of elephants, rabbits, cats, dogs, pigs, chickens, turkeys, birds, whales, fish, horses, donkeys, even unicorns. The one undisputable thing that is common to these three women is monkeys. Monkeys seem to appear in many of Szymborska’s poems as a way of commenting on humanity’s relationship with each other and with the natural world.

The Monkey

Evicted from the Garden long before

the humans: he had such infectious eyes

that just one glance around old Paradise

made even angels’ hearts feel sad and

sore,

emotions hitherto unknown to them.

Without a chance to say “I disagree,”

he had to launch his earthly pedigree.

Today, still nimble, he retains his charme

with a primeval “e” after the “m.”

Worshiped in Egypt, pleiades of fleas

spangling his sacred and silvery mane,

he’d sit and listen in archsilent peace:

What do you want? A life that never

ends?

He’d turn his ruddy rump as if to say

such life he neither bans nor recommends.

In Europe they deprived him of his soul

but they forgot to take his hands away;

there was a painter-monk who dared

portray

a saint with palms so thin, they could be

simian.

The holy woman prayed for heaven’s

Favor

as if she waited for a nut to fall.

Warm as a newborn, with an old man’s

tremor,

imported to kings’ courts across the seas,

he whined while swinging on his golden

chain,

dressed in the garish coat of a marquis.

Prophet of doom. The court is laughing?

Please.

Considered edible in China, he makes

Boiled

or roasted faces when laid upon a salver.

Ironic as a gem set in sham gold.

His brain is famous for its subtle flavor,

though it’s no good for trickier endeavors,

for instance, thinking up gunpowder.

In fables, lonely, not sure what to do,

he fills up mirrors with his indiscreet

self-mockery (a lesson for us, too);

the poor relation, who knows all about

us,

though we don’t greet each other when

we meet.

Frida Kahlo surrounded herself with animals, especially monkeys, and Dinesen found animals essential to her gothic tales, especially the third of her Seven Gothic Tales, The Monkey.

While I am not a fan of animals in the home, I enjoy them in the wild. (Note: take a look at Loving Animals in Their Proper Place). I know. I know. A dog. A cat. Maybe even a monkey. They offer companionship and a warm body to talk to. However, I have found a substitute, perhaps a precursor to the robotic love mate. Consider some past posts on this blog: Alebrijes Make Me Happy, Lucy’s CuCu Cabana, and A Puerto Vallarta Story.

So, in the spirit of these three remarkable women who have been on my mind lately, and to remedy the curious lack of monkey-related napkin art, I offer you the following monkey menagerie from my collection of Mexican alebrijes (carved wooden animals). These are not real animals. I know that. No worries. I don’t talk to them. Yet.

Blue Monkey, Mario Castellanos & Reina Ramirez, Arrazola, Oaxaca, Mexico

Blue Monkeys, Esteban Carrillo, Arrazola, Oaxaca, Mexico

Green & Yellow Monkey with banana, Arsenio Morales, Arrazola, Oaxaca, Mexico

Hanging Monkeys, Oaxaca, Mexico, artist unknown

Karate Monkey, Manuel Jimenez Mdz, Arrazola, Oaxaca, Mexico

Monkey Exercise, Mario Castallanos & Reina Ramirez, Arrazola, Oaxaca, Mexico

Group of Monkeys, Arsenio Morales, Arrazola, Oaxaca, Mexico

Trio of Monkeys, Mario Castellanos & Maria Ramierez, Arrazola, Oaxaca, Mexico

Monkeys with hats, Angel Ramirez, Arrazola, Oaxaca, Mexico

Pink Monkey, Arsenio Morales, Arrazola, Oaxaca, Mexico

Red & Blue Monkeys, Maria & Reina Castellanos, Arrazola, Oaxaca, Mexico

A monkey in the house is a terrible idea! Unless, of course, it’s willing to comb your hair and brush your teeth, do your taxes, paint your toenails, answer the phone, organize your stamp collection, trim your nose hairs, sing duets with you, and get rid of Jehovah’s Witnesses, firmly but politely.

And, hey! Why not invite napkin artists to render you some monkeys? A little mezcal, some escargots on toast, a tune on the gramophone, and I’m betting there’d be magic!

The Oaxacan Alebrijes carvers have sated my fetish. Live Monkeys, of course are kept chained like in the Bruegel painting except in Scheherazade’s and Isak Dinesen’s tales as cats and dogs should be. However, because the wooden animals may come alive at night, I always keep my bedroom door securely bolted.

They hide under your bed, wait until you are asleep, arrange you in comic poses, take pics with their Monkeyphones and post them on the Monkeynet.

You’ve got them conflated with gremlins.