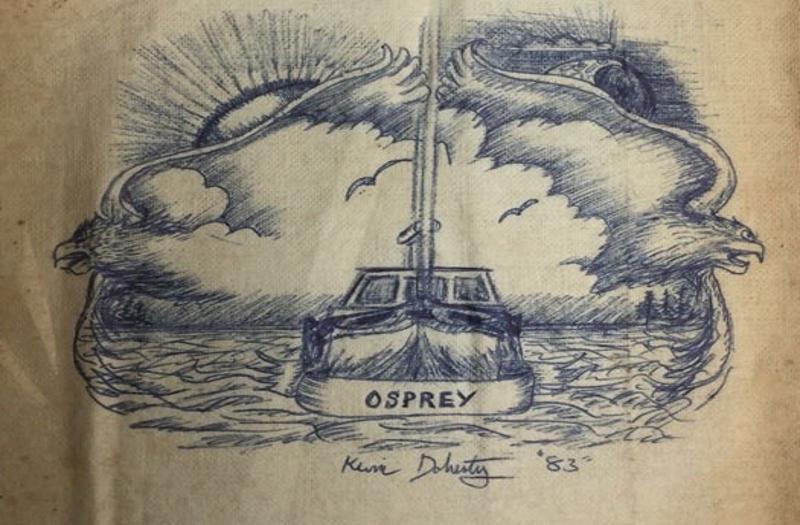

They come every spring, my osprey family. From Central America, Mexico, Baja California, along the Southern California coast back up the Pacific Flyway, to the rivers and estuaries of the Mendocino coast. To this place. To my place. There is an instinct of staying put, not inborn or hardwired, but unshakable nonetheless. It has held me here in the same house for fifty years. Something similar must account for my osprey family returning each spring, a family totem that inculcates a practical, secure, and abundant neighborhood for raising a family.

One day comes when I walk outside to be greeted by a loud persistent kyew kyew kyew. I look up and there they are, a duet of ospreys. They survived the miracle of a double journey into the void, from here to there and back. On the Mendocino coast the osprey arrives each spring the way García Márquez’s winged old man arrives in the courtyard, not as a symbol, not as an announcement, but as a fact that refuses interpretation.

They come back to the same river bend or snag, thin and weathered from their long migration, and get immediately to work, fishing, repairing their ugly stick nest, ignoring whatever meanings people might want to hang on it. Then, just as quietly, they leave again followed by their brood, vanishing south when the water darkens and the fish slip beyond sight, offering no explanation, no lesson, no farewell. This is the logic of magical realism as ecology: the extraordinary treated as ordinary, the miracle stripped of spectacle, persistence without commentary. Like the old man who flies away awkwardly over the rooftops, the ospreys yearly disappearance and return feel unreal only because we keep expecting narrative where there is only life, seasonal, exacting, indifferent to our need for meaning, and truer for it.

What do people do when an osprey appears? They call it a hawk, an eagle, a sign, a nuisance and argue about what it means. What does the osprey do? It fishes, feeds its young, and leaves. In Márquez’s story the villagers argue endlessly about whether the old man is an angel, what he should be called, and what he should do for them. Meanwhile he eats, gets sick, heals, and eventually flies away. He doesn’t collaborate in their myth-making. That’s exactly how an osprey behaves in a human world.

David Gessner’s book Return Of The Osprey is full of osprey facts. Ospreys have been around a lot longer than us: “Scientists have found an osprey-like fossil from thirteen million years ago, in the mid-Miocene era, and some evidence suggests the birds were common in North America as far back as fifteen million years ago.”

“An osprey’s vision is almost eight times greater than a human being’s, but that only begins to hint at their acuity. All birds rely heavily on vision, predators in particular. Like all diurnal birds, ospreys see the world in living color.”

Ospreys have their own unique way of being: “Resting, hunting, mating, diving, plunging, building big sloppy nests, tearing into their prey—they live the way they live.”

“Ospreys were never trained to hunt and do the bidding of humans.”

“On some level the birds understand that their first places are, practically speaking, places that served their parents well and will likely serve them well, too.”

They migrate in spite of immense danger: It’s “a brutal journey from which fewer than half of them will return … “almost two-thirds of the young will never” make the journey down and back.

“I read all the theories about what prompts their coming journey—instinct, food, the tilt of the earth, fading daylight—and I read about what guides the birds—sun, stars, ancient pathways, earth’s magnetic field, and some mysterious inner compass—but the truth is, I can’t even begin to understand migration, not just the why of it but the how.” ” … unlike hawks, they will not be reliant on thermals and will even migrate directly over water, unafraid of offshore routes or long crossings. European ospreys routinely cross the Sahara Desert and the Mediterranean. In these instances their strong steady flapping helps; while most hawks soar, ospreys, with their long, narrow wings, are built for plugging away.”

Gessler sums up exactly how I feel about ospreys leaving and returning with wisdom he borrowed from Thoreau: “One of Thoreau’s less extreme lessons was that you can experience something profound in the natural world without going to the Himalayas, that you can find everything you need in your own backyard. In other words, you don’t need to live with grizzlies or gorillas to live deeply. We need to love the near with the same excitement that we love the exotic.”

We’re moving quickly toward spring and my friends will soon be back. The turkey vultures, ravens and red-tailed hawks are always here. They are interesting, but the ospreys are my favorite. The great horned owl, also a favorite, is unfortunately a mortal enemy of the osprey. The great horned owl is a predator. He eats the eggs, sometimes the young, and even the parents. As Tennyson said, nature is red in tooth and claw. Of course, ospreys too are predators. They spear fish and eat them alive. Squaring the circle is the same in nature as it is in geometry. Impossible.

CLICK ON THIS LINK FOR A PBS VIDEO OF AN OSPREY LEARNING TYO FLY.

An eagle represents freedom, transcendence, and escape. But the eagle has his faults. It was because eagles often perform acts of piracy on ospreys that Benjamin Franklin objected to having the bald eagle as our national symbol. Ospreys are the anti-eagle bird: practical, working, earned, and not mythic. They would have been the better choice.

He was the eagle who visits the earth, shakes the dust from its wings, and returns to the sun. (quote from my novel Behind The Locked Door)

“The Osprey” From Endangered Species Berklee Valencia students performed The Osprey, an original composition by alumnus Drew Keeve M.M. ‘25, at the concert “Endangered Species,” at CaixaForum València. Inspired by the landscapes and wildlife of Keeve’s home in eastern Washington, The Osprey reflects on the natural beauty of the region and its connection to the bird of the same name. Under the musical direction of Viktorija Pilatovic, the program featured an arrangement of Wayne Shorter’s “Endangered Species” and original jazz compositions by students from the Contemporary Performance program, two of which were written exclusively for this event.