[Click on the Blue Links for further information]

Many years ago I studied inequality. I delved into Gini ratios, the annual Current Population Surveys of the Census Bureau, and a number of distributional statistics all in a naïve attempt to answer two questions posed by the author Hao Jingfang, “the first Chinese woman to win a Hugo, conferred by the World Science Fiction Society.” The questions were: Why do we have inequality in the world? And why is it so hard to eliminate?

I tried to model the impact of unemployment and inflation and economic growth on the levels of inequality. This was the typical approach of a macroeconomist at that time. My thesis advisor was George Akerlof who went on to win the Nobel Prize. His wife, Janet Yellen, is currently the Chairman of the Federal Reserve. Many years later Akerlof wrote Identity Economics with Rachel Kranton, an interesting study that gives us some answers, not all, to those two questions. I’m afraid I dropped the ball. I did not finish my thesis. Instead I went into the restaurant business. Go figure.

I write about this now because I recently read Hao Jingfang’s novelette Folding Beijing. I heard about this book through Tyler Cohen who maintains a economics blog called Marginal Revolution. You can read Folding Beijing online for FREE HERE. I copied and pasted the book into WORD, emailed it to my Kindle account, and read it on my iPAD. It’s an efficient process or at least I think so.

“The ‘cash-value’ of studying philosophy is very real.”

Robert Hagstrom from Investing: The Last Liberal Art

Hao Jingfang is young, smart, and multi-talented. I am jealous on all fronts. As Tyler Cohen says on his site: “It is an extraordinary short story, one of the best things I’ve read all year, and it’s proof positive of how rapidly China is becoming a society supercharged with creativity. I am pleased to see it received a Hugo Award for best novelette. [Hao Jingfang beat out Stephen King to win the award.] Did you know she is a macroeconomics researcher at a quango in Beiging? One key part of the plot and premise revolves around macroeconomic theory.”

While I was not (but am now) a fan of science fiction, I did know of the Hugo Award because of the “law” of six degrees of separation. With the restaurant I purchased in Mendocino California, the Sea Gull, I inherited an eclectic group of customers and staff. One of the customers was Chester Anderson who wrote The Butterfly Kid, a science fiction novel nominated for the Hugo Award for best novel in 1968. I recently read quite a lot about Chester Anderson in Jubilee Hitchhiker, a biography of Richard Brautigan. I wrote about Brautigan in an EARLIER BLOG HERE.

Okay. So much for coincidences or six degrees of separation. The fact is that there is much to be learned about economics and money and investing from reading widely in the liberal arts, a fact attested to by none other than Warren Buffett. Warren and his sidekick Charlie Munger consider “stock picking as a subdivision of the art of worldly wisdom.” I have listed a few of my favorite novels dealing with economics and money at the end of this blog. Read them all and you will be a better investor or a better person or maybe you will just avoid watching boring TV shows and that ain’t so bad.

“I must say that I find television very educational. The minute somebody turns it on, I go to the library and read a book.” Groucho Marx

John Kenneth Galbraith once said that artists know nothing about economics, and economists know nothing about art, so they will have little to say to each other. Hao Jingfang is a wonderful exception.

“We see from history that, at the beginning of every new empire, equality was one of people’s aspirations, but as the empire grew older, inequality appeared again, and people had to overthrow the empire and start all over again. It seems even now there isn’t an ideal solution. Inequality will continue to be a challenge for human society in the future.” Hao Jingfang Interview NYT

Hao Jingfang

Inequality has been a hot topic since Thomas Piketty’s unlikely best seller Capital in the Twenty-First Century. And then there is Donald Trump. Donald Trump’s tweets have put China in the news and apparently at odds with the United States. Piketty’s book and Donald’ Trump’s tweets make Folding Beijing a contemporary read even if you aren’t a fan of fiction or science fiction. And, consider this. There is a long tradition of writing about the idle rich.

“If dishonesty can live in a gorgeous palace with pictures on all its walls, and gems in all its cupboards, with marble and ivory in all its corners, and can give Apician dinners and get into Parliament, and deal in millions, then dishonesty is not disgraceful, and the man dishonest after such a fashion is not a low scoundrel. Instigated, I say, by some such reflections as these, I sat down in my new house to write The Way We Live Now.” Anthony Trollope

Of course, it’s not the past that interests us but the future and the present.

“Most people care only about the details of their individual lives: family, love, power, and wealth, and few examine the framework of the world as a whole. The structure of the real world, of course, is also unfair and unjust, like the world in the story, and in fact the real social pyramid may be even more extreme than the one portrayed in my tale. Only someone who can take the perspective of a reader of the world, standing apart from the emotional experience of individuals, can perceive this structural framework. I wanted to reveal this perspective.” Hao Jingfang interview NYT

Hao Jingfang

The economist Alfred Marshall defined economics as “the study of mankind in the ordinary business of life.”

Art that expresses the ordinary business of life in new or different ways, that takes hold of the viewer and transforms him forever, becomes lasting art. I think of the Mexican muralists at the turn of the last century, Rivera, Orozco, Siqueiros or of Frida Kahlo or her friend who lived for a time in Mendocino, Emmy Lou Packard. In a small but similar way, Hao Jingfang’s story impacts my life. That is why I chose to write about it.

“I talk about the future in the story, but the inspiration is current life. In today’s society, although people might live in the same city, their lives are very different, and they have little connection to one another. I wanted to show this in the story in a more direct way — the idea that people live together but can’t see one another. I want people to realize that there are so many invisible people in their lives. And also that their decisions, no matter how harmless or small they may seem, might have a huge and irreversible impact on other people’s lives.” Hao Jingfang interview NYT

Hao Jingfang accepts her Hugo Award on this YouTube Clip.

Scott Fitzgerald in The Great Gatsby told us about the rich: “Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me. They possess and enjoy early, and it does something to them, makes them soft, where we are hard, cynical where we are trustful, in a way that, unless you were born rich, it is very difficult to understand.”

It may be silly for me to dwell on how much this short story impacts me. I’m not a literary or an economic expert. The comments following Tyler Cohen’s post on Marginal Revolution often seem like sniping. Who, for example, but a professional economist would care about the Baumol effect? And, does everyone agree that fiction “like music” should be “written to entertain the consumer, not make political points?” Perhaps. I don’t pretend to know the tastes of everyone. But, I do know my own tastes. I hope the author writes many more and someday gets to write that history of inequality.

Read the story. As I said, it’s FREE ONLINE. It took me less than an hour. What have you got to lose?

Some of my favorite quotes from the book are pasted below. And, further down a reading list.

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Roy Hoggard artist

EXCERPTS FROM HAO JINGFANG’S FOLDING BEIJING

Time had been carefully divided and parceled out to separate the populations.

Lao Dao had lived in Third Space He understood very well the reality of his situation, even without Peng Li pointing it out. He was a waste worker; he had processed trash for twenty–eight years, and would do so for the foreseeable future. He had not found the meaning of his existence or the ultimate refuge of cynicism; instead, he continued to hold onto the humble place assigned to him in life.

The young were no longer so terrified about survival; they cared far more about appearances.

Two small robots dressed in plaid skirts greeted them, took Yi Yan’s purse, brought them to a booth, and handed them menus.

“It’s no big deal.” She stuffed the bills into his hand. “I earn this much in a week. Don’t worry.”

There were a considerable number of people in First Space like him—chefs, doctors, secretaries, housekeepers—skilled blue-collar workers needed to support the lifestyle of First Space.

Crackers and dried fruits were set out next to the vases for snacking, and a long table to the side offered wine and coffee. Guests mingled and conversed among the tables while small robots holding serving trays shuttled between their legs, collecting empty glasses.

Currently, the service industry of our city is responsible for more than 85 percent of our GDP, in line with the general characteristics of world-class metropolises. The other important sectors are the green economy and the recycling economy.

“Things aren’t that simple, if I approve your project and it’s implemented, there will be major consequences. Your process won’t need workers, so what are you going to do with the tens of millions of people who will lose their jobs?”

“You might as well go back and enjoy the meal. I’m sure you understand how this works. Employment is the number one concern. Do you really think no one has suggested a similar technology in the past?”

“They were talking about automatic waste processing earlier. Do you think they’ll really do it?”

“Hard to say.” Lao Ge sipped the baijiu and let out a burp. “I suspect not. You have to understand why they went with manual processing in the first place. Back then, the situation here was similar to Europe at the end of the twentieth century. The economy was growing, but so was unemployment. Printing money didn’t solve the problem. The economy refused to obey the Phillips curve.”

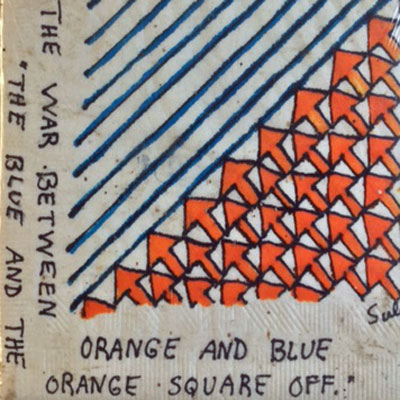

Sea Gull Cellar Bar Napkin Art, Sula artist

He saw that Lao Dao looked completely lost, and laughed. “Never mind. You wouldn’t understand these things anyway.”

“As the cost of labor goes up and the cost of machinery goes down, at some point, it’ll be cheaper to use machines than people. With the increase in productivity, the GDP goes up, but so does unemployment. What do you do? Enact policies to protect the workers? Better welfare? The more you try to protect workers, the more you increase the cost of labor and make it less attractive for employers to hire people. If you go outside the city now to the industrial districts, there’s almost no one working in those factories. It’s the same thing with farming. Large commercial farms contain thousands and thousands of acres of land, and everything is automated so there’s no need for people. This kind of automation is absolutely necessary if you want to grow your economy—that was how we caught up to Europe and America, remember? Scaling! The problem is: Now you’ve gotten the people off the land and out of the factories, what are you going to do with them? In Europe, they went with the path of forcefully reducing everyone’s working hours and thus increasing employment opportunities. But this saps the vitality of the economy, you understand?

“The best way is to reduce the time a certain portion of the population spends living, and then find ways to keep them busy. Do you get it? Right, shove them into the night. There’s another advantage to this approach: The effects of inflation almost can’t be felt at the bottom of the social pyramid. Those who can get loans and afford the interest spend all the money you print. The GDP goes up, but the cost of basic necessities does not. And most of the people won’t even be aware of it.”

Lao Dao listened, only half grasping what was being said. But he could detect something cold and cruel in Lao Ge’s speech. Lao Ge’s manner was still jovial, but he could tell Lao Ge’s joking tone was just an attempt to dull the edge of his words and not hurt him. Not too much.

“Yes, it sounds a bit cold,” Lao Ge admitted. “But it’s the truth. I’m not trying to defend this place just because I live here. But after so many years, you grow a bit numb. There are many things in life we can’t change, and all we can do is to accept and endure.”

Fate now pressed into his chest. Of everything he had experienced during the last forty–eight hours, the episode that had made the deepest impression was the conversation with Lao Ge at dinner. He felt that he had approached some aspect of truth, and perhaps that was why he could catch a glimpse of the outline of fate. But the outline was too distant, too cold, too out of reach. He didn’t know what was the point of knowing the truth. If he could see some things clearly but was still powerless to change them, what good did that do? In his case, he couldn’t even see clearly. Fate was like a cloud that momentarily took on some recognizable shape, and by the time he tried to get a closer look, the shape was gone. He knew that he was nothing more than a figure. He was but an ordinary person, one out of 51,280,000 others just like him. And if they didn’t need that much precision and spoke of only 50 million, he was but a rounding error, the same as if he had never existed. He wasn’t even as significant as dust. He grabbed onto the grass.

SOME RECOMMENDED NOVELS

(Novels concerning economics, money, inequality. Not science fiction)

Dickens Little Dorrit

Anthony Trollope The Way We Live Now

Frank Norris, The Pit, The Octopus, Vandover and the Brute

Tom Wolfe The Bonfire of the Vanities

Kurt Andersen Turn of the Century

F. Scott Fitzgerald The Great Gatsby

Money Émile Zola

Christina Stead House of All Nations

Money A Suicide Note Martin Amis

Avenue of Mysteries John Irving garbage kids

Eric Maria Remarque The Black Obelisk