A typical winter day: cold, clear, calm, quiet. I walked downstairs from the bedroom in the house next to the restaurant, the historic Jacob Stauer House. In the kitchen below, I looked out the window into the garden behind the Inn. There wasn’t much left of the vegetables and flowers in the raised beds. The climbing rose that covered the trellis along the rambling walkway between the Restaurant and the Inn was healthy and green but the roses were gone. South of the restaurant’s back stairway through an opening in the whitewashed fence, a huge red and green holly bush leaned toward the Rosemary room at the Inn. Above Big River there wasn’t a single car on the highway.

Something was wrong. I put my head closer to the window to get a wider view. A thick stream of dark smoke was billowing out the chimney on the south side of the Restaurant. The chimney rose from the Cellar Bar, below street level, to a point above the cement block firewall just a couple of feet away from the Mendocino Volunteer Fire Department. Any fire in the bar from the night before should have burned out by six in the morning. My heart started to pound. I walked quickly into the storage room, originally the family room of the house. It was connected to the restaurant via a narrow hallway. The faint smell of smoke grew stronger. I tried the door to the hallway. It blew open hitting my arm. A blast of hot air hit me, and I fell to the floor. I struggled to close the door with my feet. A word formed in my mouth, but my dry throat made it impossible to speak. A word, barely audible, slowly emerged from my lips: “Fire.” I tried again, louder. “FIRE.” By the time I managed to push the door closed with my feet, I was yelling at the top of my lungs: “FIRE! FIRE! FIRE!”

The Sea Gull Restaurant was constructed in overlapping stages. It emerged like a dinosaur out of a swamp without an overall plan. The dining room and restrooms had been tacked on in the Sixties by Martin Hall. The Cellar Bar was conceived during the same period. A walk-in box was built in place of the old restrooms next to the kitchen. Previously there was been a vacant lot between the firehouse and the restaurant where the Hall children occasionally sold hotdogs. The hallway connecting the restaurant to the house next door was built in the Sixties, probably at the same time the porch on the west side of the house was converted into a wine storage room. Two upstairs bedrooms were added to the residence. Restaurant repairs were made when needed in a hodgepodge manner. Someone would get the urge to paint a wall in the kitchen when business was slow. New floors were laid on top of old floors. If a piece of equipment was in the way, it was seldom moved. The floor was laid around refrigerators and freezers creating an uneven and irregular surface that was interesting but impractical. Just a year before the fire, the kitchen was remodeled. The walls were redone in sheet rock. The uneven floor was patched up, prepared and covered with ceramic tiles. A metal fire door was installed at the end of the hall leading to the house. These improvements and the fast-thinking highly-skilled volunteer firemen saved the residence that winter day when the restaurant burned to the ground.

The original restaurant building had served as a blacksmith shop, a church, a bus depot and a bar before becoming a restaurant. The bar was called The Little Place. A giant red Bull adorned the entrance. Later the Bull was moved to “the miracle mile,” as Chance Sears called it, that odd jumble of businesses south of Fort Bragg. It stood outside Hannigan’s bar. The Little Place was transformed into a restaurant called Casa Mendocino. When the Hall’s arrived in the Sixties, they acquired an old Victorian to the east of the fire department. They converted it into an Inn with nine rustic rooms. Each was named according to some aspect of the surrounding environment: The Lookout, Geranium, Rosemary, Fuchsia, Driftwood, Abalone, Sea Urchin, Sand Dollar, and an out-building called The Barn. Later, after the fire, a storage room across from the Rosemary was remodeled in the same rambling style as The Barn. This final unit was simply called The Shed. The Lookout was later divided into two adjoining units called Lookout One and Lookout Two. The old Inn remains, improved but intact.

A jolly old man painted into the concave side of a large round tin advertising tobacco stared out at the Sea Gull Coffee Shop from his perch high on the wall above the front door to the restaurant. Prince Albert. Some thought his ghost roamed the restaurant at night. Others were attracted by his jovial presence. The restaurant decor was an odd mix of eclecticism, mostly junk, “happy crappy” as Martin liked to call the artifacts and related paraphernalia that adorned the Sea Gull. He said antique was too generous a term. The staff identified various locations in the restaurant by the décor. There was the Big Back, the largest table in the restaurant and strategically placed in front of the large back window. Chekova, a cantankerous calico cat, would sometimes chew on an unlucky mouse in full view of the window to the disgust of unsuspecting tourists trying to enjoy breakfast or lunch. There was the Front Round, popular with many of the locals, and the Back Round for threesomes. The Eagle was a deuce in the front by one of two old stoves located at each end of the dining room. It was named for the framed flag and eagle emblem that hung above the table. The Baseball was the last deuce before the back entrance to the kitchen. There was a framed baseball scene on the wall which separated the table from the back wait station. There was the Kitchen Wall (tables on the north side) and the Firehouse Wall (tables on the south side). The Firehouse Wall was a favorite station for the waitresses (there were more waitresses than waiters). The tables on that side turned over quickly. It was the best section for tips. The Firehouse Wall was divided from the front by a spiral staircase that lead to the Cellar Bar. A corner was created by the part of the floor cut out to accommodate the stairway. It was called the “L” and sat four people. This was where our friends, Terry and Judy, joined Cathy and I for dinner on the night before the fire.

The two sides of the dining room were separated by five large wine barrels stacked three on bottom and two on top. The wine barrels were covered with lots of “happy crappy” but there was an especially beautiful white sculpture of two men playing chess, a real antique. The sculpture was destroyed before the fire, but that’s a story of its own. There were a number of other tables, deuces and fours along both walls, but those already mentioned provided the general bearings for the staff. Prince Albert could see little of the dining room, perhaps the Front Round, the Eagle, and the spiral staircase, but he did have a Birdseye view of the register area and the Coffee Shop. This was where the real action took place.

Contractors, electricians, plumbers, farmers, loggers, truck drivers and delivery folks sat next to attorneys, doctors, reporters, politicians, and tourists. There was also a growing counterculture of mostly younger people moving to the coast. The staff was equally diverse. Few considered themselves career restaurant employees. Many were artists trying to cover the rent: musicians, astrologers, sculptors, painters, actors, poets, authors, and, of course, philosophers. Most of the janitors had Ph.D’s or Masters Degrees in Physics, English, and Music and one was an attorney. One bartender had a day job as a barber. Another was an artist and for a time the Director of the Mendocino Art Center. A part time cook was also a registered nurse. Schoolteachers moonlighted as cashiers, bartenders, and servers. Much of the town’s business took place in the Coffee Shop—the town gossip originated and disseminated. The coffee shop was open early to late. It was the first place where local events were reported, sometimes even happened.

Prince Albert gazed down upon all of this with his comforting smile. I’ll never know if his ghost roamed the restaurant. I sat in the Coffee Shop alone in the dark after the janitors were gone. Not once did I see a ghostlike flicker. Perhaps I was incapable of detecting ghosts. It no longer matters. Early on Sunday morning, December 12, 1976 any ghosts that inhabited the Sea Gull were set free in the flames that totally destroyed the building. Outside it was a cold winter day when the restaurant burned to the ground. Inside it was like the derelict Alice May stuck on the marge at Lake Lebarge when the flames soared and the furnace roared during the cremation of Sam McGee.

Article Below Transcribed from California Living, The Magazine of the San Francisco Sunday Examiner & Chronicle, February 13, 1977

Farewell to The Sea Gull

By William Luvaas

We walk quickly up Lansing toward three Pacific Telephone rigs with crane-neck ladders men in crows’ nests splicing lines, quite routinely, above the trill of bystanders. This is the corner where trunk lines junction and old cables are shriveled like firework snakes. Behind them the Sea Gull Inn props its charred skeleton in jagged fragments—a wall section here, casement there—structural shreds in a Eugene Berman painting, isolated on a hopeless plain. A bay window juts gauntly like the prow of a death ship, eyes gaping.

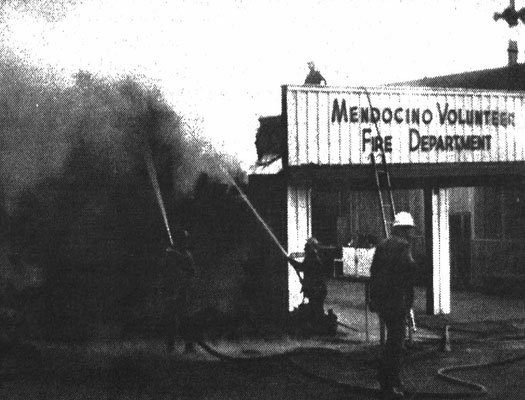

The fire is out but a poignantly sour mephitis of charred wood hangs its pall over the morning. The front wall has toppled drunkenly upon the sidewalk; the rear remains gratuitously but the roof has caved into interior shambles … gutted! Wall gaps boarded iup with plywood to keep out the curious or to keep in ghosts. A side wall constructed of concrete blocks remains intact, fireproof but for vitrified veins of mortar. It has saved the adjacent building from destruction. Photographers busily work out free exercise routines—bending, leaning, stretching—pursuing that perfect shot for Life magazine’s defunct “Photo of the Week,” a gutted restaurant right next door to the Volunteer Fire Department.

Photographer Lucinda Luvaas

An architect’s premonitions extant in that concrete wall: one day this would happen and the town would need its firehouse to quell the blaze. As it is, the house in back, the owner’s house, is browned like a good sirloin.

Photographer Lucinda Luvaas

Another irony: the sign out-front rests untouched, indifferent against its vestibule. “Sea Gull Inn” it says, hinting elegance (like a lattice on the Ukiah Street side, metamorphosed to charcoal). A proud boast, “I am down but I am not finished.” Though the gull itself, from its bracket overhead, has flown away on winds of Carthage.

Firemen gather out front, some in scarlet jumpsuits, mostly old-timers, scowling in those tried reposes of men haunted by intent. They are dog-beat-tired, mttering statements terse and trenchant as slivers of wood. Their mute obituary lingering over the cold ashes of collective defeat. They huddle together glancing a bit suspiciously at bystanders: “What do they know about it? By Golly! It went up like a tinderbox, wasn’t nothing could be done.” They stand between firehouse and fire holding the world at arm’s length with proprietary scowls.

A man stands amidst them: dark glasses, down vest, chewing gum like a nervous New Yorker, glancing quickly side to side, attempting to be one of them in an acute poise of determined nonchalance. No one is fooled.

Milling about square-jawed, reluctant to leave, faces locked in visions of defiance. A close call. Too damned close! They glance thoughtfully at the concrete wall.

Nonetheless, the town is proud of them—proud since 1947 when the department was formed (many of those original volunteers are here today). They have lost the battle but won the war: surrounding structures stand untouched. These are the men who risk their lives early Sunday morning, who pull visiting skin divers from the surf, who stand as a tribute to something fine, and nearly lost, in America—neighbor helping neighbor without though of reward—who know that this is the only way it can work. The town loves its firemen. They have a right to scowl.

Bystanders muse quietly. Now and again glancing overhead at splicers mending telephone wires. A feat to baffle a neurosurgeon. One man unfolds a penknife and slits the plastic wrapping about a new cable—wide as his arm; varicolored hundreds of wire flare into his hand; and now, slightly smiling, he must find a partner for each one. Today he is earning overtime.

Cars crawl reluctantly by. The curious lounge on curbs, form small groups, discussing. Did it start in the kitchen? What kind of heating? Was it arson? (Everyone turns to look.) No! Don’t be ridiculous! They say it was a cigarette in an overstuffed bar chair. Strangers come together like old and intimate friends. They hug or nod their heads. For here is something they hold in common, not just this wasted landmark and corner crossroads, but the vicissitudes of life itself. Communion that comes with anything dwarfing and final—and nothing is more final than fire. Beyond that there is the irony. Smoke is final and yet, as Turgenev says, smoke is shifting, always shifting, with the caprice of fate. “All is vapour and smoke … all seems to change continually … everything hurries, hastens somewhere – and everything disappears without a trace, attaining nothing …” It is this to which we are unreconciled, this wantonness of change which brings us together in commiseration. Yet there is a near carnival atmosphere here, a raw excitement, awed only slightly by our resignation.

On barber shop steps across Ukiah Street sit cashier and waitress. They arrived for breakfast shift … to this! They gaze, stunned and jobless, at the still carcass.

A woman in chic scarlet evening jacket and matching scarf strands rapping in dull annoyance with her male companion as though they had come for lunch to find ashes. A few last beads of water drip from an obtruding joist, a bone torn through the flesh of symmetry. What is colder, what is deader and less warming than a smothered fire?

The Sea Gull Restaurant and Bar in Mendocino was born circa 1920, died at dawn, December 12, 1976.

The Sea Gull was a place where people gathered, where ranchers stopped for lunch, tourists for dinner, woodsfolk for breakfast. It was woodwarm and weathergray with a great chunk of driftwood out front.

Seventy-five years ago or so, Preacher Smith built the front portion and called it Gospel Hall (smith also raised apples and sold groceries). Later it was a tavern (the Little Place” ?); then, in the late fifties, a beanery (the Casa Mendocino”?). In 1960 (?) Martin and Marlene Hall bought it, added dining room and bar and it became the Sea Gull. They sold in 1973 to David and Cathy Jones. (A history compiled from many sources—no one remembers for sure. As one old resident told me, “I don’t pay it any mind;” like other institutions, she expected it to be around forever.)

Behind me Marshall says, “Man, that’s where I met everyone around here.”

Seven year old Iana dreamt of fire a few minutes before the alarm rang. When she got there at 7:45 the roof was sagging, flames licking out the windows.

I recall a time in Berkeley when the living room wall began to glow; outside, the sky was pale magenta. “My God,” someone shouted, “it’s finally happening!” We ran into the street amidst gogglers in bathrobes and towels to half a block of crackling apartments.

Another time: a neighbor was burning brush in the Sierras on a windy afternoon; fire jumped the creek; we shoveled dirt frenetically from above; flames fanned up hill and kissed the eyebrows from my face—in one adrenalin howl of escape I threw both neighbor and myself over a barbed wire fence.

Fire. A fascination. A horror. Nothing more beneficent and warming, nothing more malevolent.

The week before the Windsor hotel burned in Fort Bragg. Now we hear Jimmy Reed is dead. A well known and beloved figure, indigent poet and pianist, forty-two years old. He burned to death in an old Albion garage: his clothes caught fire while he slept … another cigarette.

The day after the fire I am standing watching soot blackened, beer swigging laborers sift through the Sea Gull rubble. To one side charred bread loaves fill a rack. A former employee tells me they are volunteers; they want to salvage something, like the firemen who saved the sign. “Luckily there wasn’t the smallest breeze,” she says, glancing at the house. “It’s really hard to describe what it meant to us … it was our gathering place. Everyone came here – old ranchers to young street people … Now where will they go? … Where will we work?” She stares inconsolably into the debris.

“Maybe it can be rebuilt,” I suggest. She shakes her head as if this proposal is too tentative.

“That’s not the point,” she says; “the town needs it!”

Posters announce a benefit boogie for employees at the Foghorn Tavern across the street. Going to be a lean Christmas.

In a storeroom crammed with cartons and books, I talk with proprietor David Jones. He sits in a sweatshirt on cartons of canned fruit – a vigorous man, just beginning to gray at the temples. Soot has worked deeply into the fissures of his palms. He sighs inadvertently, lacing fingers behind his head. “We were just beginning to make it … Cathy and I had gotten it down from twenty to twelve hour work days.” He goes on to explain with wry humor that they were “heavily underinsured” – with soaring rates they couldn’t afford full coverage.

“If we sold right now,” he smiles ironically, “we could probably get out broke.”

Jones outlines the sequence of events. The cellar bar closed at 2:30 a.m. and at six, as usual, he came down to open for employees. Already smelling smoke before he opened a hallway door between house and restaurant. Hot gases knocked him down; he slammed the door (but the fire had caught its breath). He awakened the sleeping household, shouting to them to call in the alarm while he ran down Lansing Street to fireman Skip Jones’ house. Looking back, down the empty street, he saw flames spewing six feet from the bar windows downstairs. He knew it was bad.

Men came running from all over town. They got hoses on it immediately but hot air had been pouring up the open stairwell into the restaurant all night; windows began to explode, more oxygen rushing in to feed it. “Flames really started mushrooming.”

According to Fire Chief Foggy Gomes, the alarm is sent directly to volunteers’ homes via a plectron system, giving them the exact location of the blaze, bypassing the time profligate need of a central meeting place. But when the men arrived, flames were blowtorching out of blown windows onto the street, hovering out at an angle from the big bay window, temporarily blocking access to firehouse doors and the trucks. Little more can be accomplished in the face of such a conflagration than containment. Chief Gomes wasn’t as concerned ultimately about the firehouse as about the Jones’ home in back. They pumped eight to ten thousand gallons on the fire from a portable canvas reservoir set up in the street – a contrivance designed for just such an emergency. Four trucks, including State Forestry and Civil Defense rigs, arrived from Fort Bragg and, together with a privately owned tanker, served as “shuttle” to keep the reservoir full, bringing wter from the high school and the Masonic lodge.

Two shaky hours: groggy Sunday morning firemen, coarse shouts, blackened faces, thick, unnavigable smoke, an unnerving fear that water wouldn’t hold out. For a time, says Jones, it looked bad: flames licked the house, the Masonic water tank was nearly depleted. (Mendocino’s water shortage is chronic this year; many wells dry; a heavy tourist season without rain.) Just in time, the big tank truck arrived from Fort Bragg, and by 8:20 a.m. they had the fire controlled. Jones had words of praise for the volunteers.

A brawny fellow looks in while we are talking, says he’s off to Unemloyment, he’ll be back later. Jones thanks him. “We had a fantastic staff,” he tells me (forty to fifty people, an estimated tenth of the town’s work force). “Some have worked here for years.” He doesn’t know where they will find employment. He is genuinely concerned about them. They are donating labor to clean up the mess. “Everyone has been very helpful,” he says. There is talk of a benefit next Wednesday night and a bake sale; the former owner, now dealing in antiques in Scotland, has offered to help refurnish … all kinds of incredible suggestions. Someone has evej proposed they rebuild it cooperatively, carpenters volunteering their time; this remains a possibility. I have the feeling the Joneses are not so much proprietors as administrators of a community asset, and I am thinking that here is a town that not only douses its own fires but rebuilds afterwards in the same spirit.

Jones needs time to think it over. He says he wants to rebuild if he can find the money. Though he can’t hope to duplicate the former structure exactly, he wants to duplicate the atmosphere. Sea Gull II.

Buying firm at the photo shop, I mention to Spencer, who had a fire at his home last week, that the cold dry weather must be responsible. “Noooo,” he answers tentatively, “the hotel, the Sea Gull, Jimmy Reed … I don’t think it’s that … I think something else is happening.” He doesn’t say what it could be.

No more cozy evenings in the Sea Gull Cellar on soft pillows in the vaguely frowsy casbah of mismatched antiques, Turkish tapestries, blowfish lamps and copper kettles, loud jazz, competing voices and too many bodies. It wasn’t feasible to hold conversations on that long couch along the wall; nonetheless, the place was homey.

No more morning coffee upstairs through the drizzly cloister of winter.

But that’s not half of it. How will we recognize town without the Sea Gull? (Remember the day the Sutro Baths burned, or St. Mary’s Cathedral?)

A part of us has died. Here, long before the more pretentious places – refurbished hotels and historic houses turned eateries – before many of these bystanders, before the woman in carmine evening wear and the subtlest touch of eye shadow, cigarette poised delicately in arched fingers, before retired professors strolling, hands a-pocket, beards shading gray – a scene days when this “village” was a retreat for artists and the few who “knew,” when the Halls were still owners and we held jam sessions each Friday night, clacking spoons or blowing across bottle lips, when Harry the Greek taught folk dancing and threw his wine glass against the wall, and Martin yelled, “Damn it! Those are crystal!” and Harry threw another, until they served him wine in plastic cups.

No more Sea Gull or Jimmy Reed sitting at the bar, nursing a beer. Town won’t be the same without them. But I must conclude lest my obituary turn maudlin. We expect changes, but as one shopkeeper put it succinctly: “This is a little too abrupt.”

I will never forget the night that the Sea Gull burned down. We were sleeping in the second floor bedroom when we heard David yell fire.